author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 12/02/2024

- No Comments

- Politics

share

Much of the international debate on sustainability focuses on individual behaviours. This criticism is the same, whether you are a farmer from Canterbury or Jeff Bezos in the United States. However, the influence of the mega-rich and their entourage, through their investments and their control of the framing of the climate debate, is much more important than how many flights they take in their private jets.

Image: Billionaires Bill Gates, Richard Branson, and Mike Bloomberg, with other wealthy individuals who fund climate projects. Francois Mori/AP.

In an interview with Sophia Money-Coutts on Tatler in 2018, Johan Eliasch said something which reveals the attitude of many rich people towards climate change. She reports him saying in their interview:

‘I can do anything I want because I’ve got my rainforest,’ he says, smiling. ‘I’m probably the most carbon-negative individual in the world.’

Eliasch is part of a special class of people: the global elite of the mega-rich. He is worth an estimated 3.6 billion GBP, or $7.5 billion NZD. As well as being Chairman of the sportswear company HEAD, Eliasch has held various positions in the British Conservative Party relating to the environment, and runs an organisation called Cool Earth dedicated to protecting the tropical rainforest. He bought 1,600 km2 of Amazonian rainforest in 2005, and closed down all logging operations on the land, which he is now ‘protecting’ for the good of everyone.

In 2008, he wrote a report for HM’s Government in the UK about the possible benefits of using financial mechanisms to preserve forests and prevent deforestation. This report then went on to become influential in guiding policy decisions for the development of REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation), a global initiative which is part of the International Climate Change Convention. This initiative means that he can earn money on the land in Brazil that he is protecting from deforestation.

The same story is told countless times over, for countless other mega-rich people, in the study by Edouard Morena, Fin du monde et petits fours: Les ultra-riches face à la crise climatique (End of the world and petit fours: the mega-rich face the climate crisis). According to an Oxfam report, in 2019, the richest 1% of people worldwide were responsible for 16% of global carbon emissions: the same as the emissions of the poorest 66% of humanity (5 billion people). Despite their obvious personal implications in causing this crisis, these wealthy individuals saw an opportunity to increase their power, their fortune, and their wealth. They decided to take action on the back of the crisis.

Morena shows in his book how these wealthy individuals are intentionally directing the climate debate towards a certain version of ‘green capitalism.’ This system ultimately benefits businesses and the wealthy, at the expense of the poor and the environment which the system is supposed to be protecting.

We will explore how the mega-rich, along with a group of relatively well-off academic and professional elites prevent the advent of a just and adequate ecological transition. You, the reader, could be part of a bright and connected future that is both ecologically sober and greatly fulfilling, and create this future in a way which doesn’t increase the wealth and power of a small number of people at the expense of everyone else. If there’s one thing that you take away from this article, it is that there is another way.

The Climate Glitterati and their interests

Kevin Anderson, a British climatologist, calls some of these wealthy elites the “climate glitterati.” Who are they, and what are they doing?

Each year, the World Economic Forum is held in Davos, Switzerland, where countless members of the climate glitterati come together to discuss what must be done to save the world. Thought leaders, prime ministers, wealthy billionaires, and more, are in attendance. They sit in opulence and talk about key issues such as climate change and inequality. In 2020, Morena reports, Al Gore and Jane Goodall talk about the climate crisis. Goodall blames overpopulation for the problems we have now, saying that “we wouldn’t have these problems if the population was the same as it was 500 years ago.” She repeats the same neo-Malthusian arguments that many wealthy people use to shift the responsibility of climate change onto the shoulders of someone else. It’s not us that are the problem: it’s them. Morena quips that they will be “invited again” to Davos, because they have managed to softly reassure the champagne drinkers that their actions are completely rational and safe.

These wealthy individuals and powerful people seek one thing, according to Morena: to save themselves. The champagne and small bites of food on platters continue to be served whilst discussions about the future of humanity unfold. The contrast could not be greater, yet these people seek comfort and reassurance in the face of the crisis.

They go about it in two different ways:

- One group prefers to distance themselves from everyone else, and live in a secure bubble on their own estate. They’ve bought land in New Zealand or Patagonia, where they can travel by private jet if everything turns to chaos. They can be called the survivalists.

- The other group are what we referred to before as the “climate glitterati.” They want to save themselves too, but instead of hunkering down, they prefer to travel the world telling other people how to solve the problem. They’ve realised that they have more to gain (or perhaps less to lose) by directing the global climate debate and ensuring that their interests are protected.

“Their climate emergency is not the same as our climate emergency”

Everyone is exposed to the risks of climate change. The fact is, however, we are not facing the same outcomes. The wealthy fear that their golf courses, enormous mansions by the sea, and their investments in fossil fuels will be hit by the effects of climate change. The value of their portfolios might decline, which makes them, like everyone else, anxious and fearful. They might lose power, status, or credibility. The more fiscally sober among us might fear increased prices, an unpredictable storm that wipes out an apple orchard, or an unbearably warm summer which results in the deaths of countless elderly. This is most certainly not what the ultra-wealthy are worried about.

Instead of owning up to their responsibility for the climate crisis, these billionaires want to paint themselves as heroes. We are supposed to see them as the only people who have the wealth, the ideas, the power, and the guts to save humanity from this mess (the mess that they bear a greater responsibility for, remember). They are the new shining lights of our society, and we should desire to be like them.

Just like Johan Eliasch, Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon and one of the richest people on the planet, has begun to paint himself as a climate hero and invest in climate-related organisations and schemes. After an emissions-intensive trip into space a few years ago, Bezos is said to have realised the fragility of life on Earth. Following this, he set up the Bezos Earth Fund, worth 10 billion USD, and another Amazon Climate Fund worth 2 billion USD. With this money, he has begun investing in organisations and companies which support his vision for the future. He’s also been speaking at conferences about the climate and the need to act (with technology and market-based solutions, as we will see).

Bezos is doing this to save himself and protect his assets. In order to justify being at the head of a company with an immense emissions report, and a track record of injustice and human rights issues, he must donate some of his money to support the climate effort. In doing so, he turns the attention away from the inequality that his company is responsible for, and towards the bright, shiny, technological future he is creating (for us).

As Morena writes, “It’s an indirect way of promoting yourself, legitimising yourself and putting the figure of the innovative entrepreneur at the heart of the climate debate and society in general.”

He donates so that he can continue polluting. He donates so that he can take flights around the world, and continue a high-emissions lifestyle. He donates to justify the fact that his company is responsible for huge emissions. He donates to protect his investments and his assets. He donates so that we ignore his anti-climatic actions.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Their goal: more markets, more capitalism, more technology

In a nice house in London, George Polk hosts dinner parties to educate the rich and the leaders of Western society on how to solve key social and economic problems. He’s the founder of The Catalyst Group, “a London-based organisation which works to educate international business leaders on major issues of public policy.”

Morena reports that people come to these dinners to learn about climate change, and in turn, be informed on the ways in which public policy should act to solve it. Of course, Polk is out to educate them about the possibility that business and investments can be protected through a beautiful thing called “green capitalism.” It’s possible to have your cake and eat it too.

The key aspects of Polk’s strategy to fight climate change are the same as the ideas put forward by the consulting company McKinsey, Al Gore, and a host of other elites seeking to manipulate the climate debate in a certain direction. There are two pillars to their approach towards green capitalism:

- The marketisation of nature,

- The reliance on technology and innovation

The first of these, the marketisation of nature, is referring to several schemes set up to pay people who own land and who don’t cut down the trees on that land (or who plant more trees). The idea is that wealthy people and businesses can continue to pollute, because somewhere there are trees that are sucking up all this pollution and storing it in the ground. The person who owns those trees is providing a service to the rest of society, so should be paid for that service.

This marketisation of nature takes many forms in global agreements, being referred to as a carbon credits scheme, an emissions trading scheme, the global programme REDD… This scheme benefits landowners, who extract massive profits from these schemes from companies who have no intention of changing their business plan in order to reduce their ecological impact. What’s more, in places such as Brazil, locals are being forced off land that they have occupied for generations, because this land is now owned by wealthy billionaires or companies engaged in carbon credit trading. Consequently, they are no longer able to use this land for sustenance: most of the time in ways that are sustainable and respectful to the forests themselves. Others, who are employed in the logging industry, are similarly losing their jobs, which previously was one of the only ways to make money in some of these regions. You can read the Guardian article about these communities being forced off their lands here. A similar study based in Asia on Mongabay about the communities who are responsible for taking care of forests is available here.

The Guardian also studied the effectiveness of these projects at stopping deforestation, and the real impact that they have on offsetting carbon emissions. The title of the main article says it all: “More than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows.” That’s almost ALL of their projects that have almost no ecological impact, yet they are behind an industry worth more than $3 billion NZD. The Guardian undertook nine months of research into these schemes to uncover several cases of human rights abuse, very little action to stop deforestation, and gross overestimates of the amount of carbon being stored. This article in Science concludes that “most REDD projects are less beneficial than is often claimed.”

The marketisation of nature is completed by the economic viewpoint that nature is something that renders services to human beings, each of which can be calculated and valued in monetary terms. The value of a particular forest might be $200,000; the value of a small lithium mine $2 million, and so on. Economists are therefore able to make calculations according to this about whether it is worthwhile destroying the natural environment, because now we know what it is ‘worth’. These calculations take no account of the real ecological impact of disturbing the land, and forget the fact that once we have sawed the branch we are sitting on (completely disturbed the biosphere), no amount of money will be able to get these environmental conditions back.

By valuing nature like this, economists believe that we can then act to protect the most ‘valuable’ parts of the natural environment. This will be society’s conservation project, to protect and restore ecosystems. To complement this, we need to do something about the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions which are causing global warming. For this, we need technology, the elites will say, and for that technology, we need money in the form of investments.

Investments and partnerships are another financial tool used by the elite to facilitate business despite the ecological crisis. You might have heard of green investments, or investing in green-tech or clean-tech, referring to low-carbon technological projects. These private investments are often guaranteed by the state through various banking mechanisms that mean that the state will bail out investors if their investments don’t end up creating value. Morena writes, “Their aim was in particular to transfer the risks associated with their investments in the low-carbon transition to the states – and therefore to society as a whole – and thus to participate in the advent of a “derisory green state”, to use the terminology developed by the economist Daniela Gabor.” These investors campaign for ‘green finance’ including tax credits, guaranteed loans, and public-private partnerships, to shift the risk for their investments in the future they want to create over to the society, rather than bearing this risk themselves.

The figure of the entrepreneur is a key promotional tool in order to communicate about the technological future these elites envision. Morena writes, “by emphasising freedom, innovation and the individual as vectors of social and environmental progress, this discourse contributes a little more to positioning the figure of the innovative entrepreneur, both careerist and heroic, at the heart of our social and economic imagination. [… This is part of] a broader effort to construct and present enlightened and enterprising economic elites as climate savers and leaders of the low-carbon transition.”

Those who know how to run a business, how to build a brand, how to make good investment decisions, and how to seize the opportunities of the market are, according to this story, those who are most capable of ‘saving’ societies from the risks of climate collapse. I fail to see the connection here. Understanding the functioning of ecosystems, mechanisms of life on Earth, and the ways in which humans extract and produce resources seem to me to be the most important qualities for someone who might be able to propose a solution for a collective. However, those exact skills which have led to the development of extractive and dominating business practices seem very unlikely to be the skillset to also present the solution.

Their promise hits at the heart of what many people today in the West consider as freedom, and therefore as something they are unwilling to give up: the freedom to choose what to buy, what we want to consume. To be free, for many, is an economic freedom, rather than an inner freedom or a freedom from punishment for example. We can continue to be free individuals under this scheme, because the basics of capitalist production will remain the same. The goal of becoming a wealthy and powerful individual remains, and the figure of the ‘greened’ entrepreneur, rags to riches story can remain in place. The mega-rich and their supporters are content, because we don’t have to change the story we tell ourselves about success – all we need are a series of market mechanisms and more science and technology to respond to the ecological crisis.

The method: Curves and Communications

The ultra-rich, in the beginning, were not part of international climate debate. However, through a series of coordinated actions, they have become central players through their ideas about the future, in the frameworks established at climate conventions across the planet.

Morena writes, “This state of affairs is the product of an epistemic community of researchers, experts, government representatives, NGOs and think-tanks, entrepreneurs and consultants who, through their coordinated efforts, have made it possible for the ultra-rich to join the international climate debate centred on the UN negotiations.” It is not only the ultra-rich themselves, but a collection of wealthy, educated individuals who all believe in the same mechanisms, who are supporting the story of the ultra-wealthy as climate heroes and implementing their policies in government accords.

A key player on this scene is the consulting company McKinsey & Company. Acting as a kind of glue between the ultra-wealthy and the political elites in many countries around the world, McKinsey is responsible for billions of dollars’ worth of consulting services to governments. What do they do? “McKinsey has an unrivalled ability to identify the latest ideas and trends, synthesise them, reappropriate them, amend them, repackage them and sell them back to its clients in the form of PowerPoint presentations.”

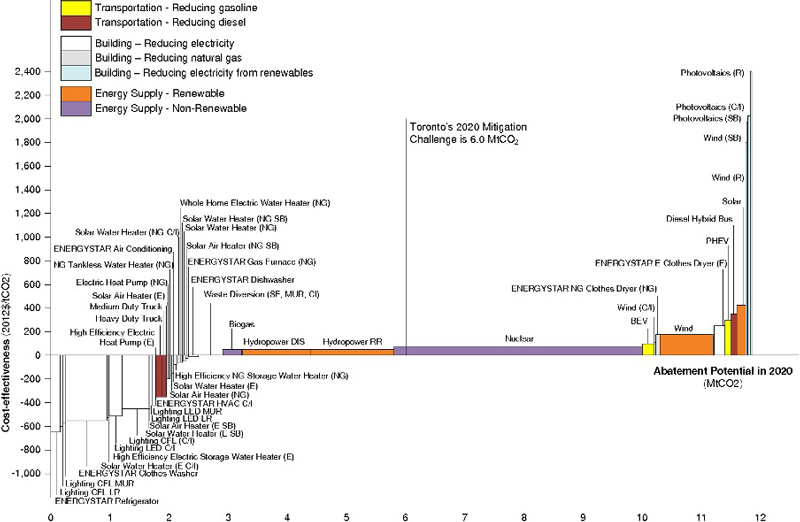

Frédérique Six, a junior consultant inside McKinsey, developed the Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC) curve to demonstrate how to decarbonise a company. These charts, or curves, tell a company which actions will most effectively decarbonise their economic activities, and the relative monetary cost of each option. In one chart, we can see the actions which cost the least and lead to the greatest carbon dioxide emissions reductions, and therefore these actions are the ones to be selected in the environmental blueprint for the company. These curves were made for all sorts of companies and states.

The MAC curve has many critics, however. In the beginning, Morena reports, McKinsey were criticised for failing to take into account certain important data in their calculations, for underestimating or omitting certain costs like non-financial costs, for making extravagant and/or unverifiable projections, and for failing to reveal just how they went about calculating the information displayed in these curves. Fabian Kesicki and Paul Ekins discuss some of these flaws in their journal article here.

Conference of the Parties, COPs around the world

Where is this message of green capitalism communicated? Now that these economic and political elites have created a ‘climate calendar’ of yearly meetings and discussion papers about the response to climate change, it is very difficult to exist as an activist outside of this calendar, and still have impact. It is at these meetings that decisions are made, even if they are made with the underlying blueprint developed in accordance with the interests of the mega-rich.

Greta Thunberg now attends the World Economic Forum in Davos, which is one of the places where climate policy is discussed among politicians worldwide. Thunberg must attend this conference, because it is there that decisions are made. However, the other participants are unlikely to listen to her real views. Not attending would be akin to having no voice, and she would lose the little impact she might have. It’s an impossible situation. Morena writes, “Thunberg’s presence in Davos is symptomatic of a wider difficulty in existing outside the arenas – UNFCCC, IPCC, One Planet Summit-type climate gatherings – which, taken together, make up what is commonly referred to as the “climate governance regime”. […] The climate movement has become structurally dependent on these elites and their political agenda.”

It’s no longer possible to have an impact as a climate activist and at the same time not attend the very meetings where countries agree on climate response mechanisms. At the COP21 in Paris in 2015, according to interviews conducted by Morena with climatologists who attended the meetings, those who could possibly have spoken out against the propositions in the Paris Agreement were silenced by a group of communication experts. They received the message: if this agreement does not pass, “you cannot exonerate yourselves from the possible consequences of your negative statements.” In other words, if an agreement is not reached, it is your fault for not supporting it – whether it represents a true and meaningful emissions reductions plan or not.

In order for the Paris Agreement and the technological and market-based mechanisms to become popular, many foundations, think tanks and experts sponsored by the ultra-rich began communications campaigns to incorporate their vision into the climate movements. They had to spread their message and their vision far and wide, so that their agreements were seen as the only possible logical and acceptable solution for all countries around the world to decarbonise their economies.

David Fenton is an expert in public communications who runs a business in the US called Fenton Communications. He specialises in public relations campaigns on environmental, public health and human rights issues. Morena uses Fenton’s analysis to detail the mechanisms through which these communications experts spread the message of the ultra-rich.

Common psychology will tell us, according to Fenton, that the brain is capable of thinking only about messages that are either true or false. Thus, we need to be either FOR or AGAINST climate action. By simplifying the message, we can create two groups of people: those who are for doing something about climate change, and those who are against it. In this way, those activists who support other means of climate justice and emissions reductions can be neutralised by reminding audiences that everyone is on the same page: we all want emissions reductions, and it just so happens that market mechanisms and technology is the way that we, the elite, have agreed to go about it.

It became possible, and is still possible, for companies to paint the picture that they are active and engaged in the fight against climate change, yet continue business as usual. When the ability to distinguish between different ‘shades’ of green is removed, everything that is painted green becomes of equal value – whether this is true or not.

The urgency of the situation is another mechanism that is used to push forward a singular agenda for fighting climate change. Because we ‘don’t have time to think of other solutions’, we need to use the ones that we currently have, i.e. markets and technology, so that we can confront the crisis. This of course ignores the many hundreds of other, well-elaborated solutions that are more democratic and more effective at responding to the ecological crisis.

How do the rich prevent change?

Hervé Kempf, a French journalist, wrote a book in 2007 called “Comment les riches détruisent la planète (How the Rich Destroy the Planet).” More than 15 years ago, the same issues were at play, and it became clear how the ideas that certain people were pushing onto the society were preventing the collective from making the decisions that were, and still are, necessary, to respond to the ecological crisis.

According to Kempf, there are four ideas that block us from changing:

- The belief in growth (especially economic growth)

- The idea that technological progress will resolve ecological problems

- The idea of the fatality of unemployment

- The common destiny of the US and Europe (and we could add, other allies).

These ideas represent a certain view of the world that is completely opposed to any kind of ecological measures. Continued economic growth, and growth in consumption, is not possible in a world with finite resources. Technological progress cannot attempt to understand, replicate, and modify natural systems that took thousands of years to evolve. All current trials of technologies don’t show much promise in a time frame that we would need them, and require immense resources to run and deploy. That’s not to mention the risks involved in their deployment. Unemployment is a way for the capitalist system to ensure low wages to keep the costs of production down. However, the green transition involves the creation of many, many jobs across the world. Finally, the US and Europe are not on the same path: Europe follows most of its climate pledges, the US does not (or does not even engage in making pledges). Similarly, New Zealand following these Western powers prevents any kind of original and local solutions from emerging.

If these ideas are the ones that are dominant, and are stopping us from changing, it seems evident that we need new ideas. We have them. However, they are not taken up. Why? Kempf provides several reasons:

- The elites (our politicians, CEOs, investors, and many academics) are trained in economics, politics, and engineering. Not in ecology. It’s a natural human bias to tend to minimise the impact of the things we don’t understand.

- We favour an economic representation of everything in society and in nature.

- People continue to give responses like, it’s not a big problem, we have technology and science to save us

- The way of life of rich people is cut off from the reality of climate change and social inequality. They don’t see the problem, so cannot imagine what the impact is.

- The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 meant that capitalism had a chance to sink its roots deeper into societies the world over, and any other forms of social organisation were ignored for some time.

We can see these ideas playing out on an everyday basis. When it comes to constructing a new road, Governments prefer to look at a cost-benefit analysis, rather than an ecological impact report. They think it’s possible to weigh up the cost of a project against the damage that might be caused to the environment, when in fact these are two completely different things. We also see that very, very few politicians and CEOs have any training on climate change and the ecological crisis. If they don’t understand something, of course it will not be seen as particularly important. And finally, a belief in the new ‘God’ of science and technology coming to save us continues a narrative of non-action, rather than taking necessary steps today to solve the problems we face.

The problem of ‘truth’ in the climate debate

After having read this article, you might be thinking: well, how do I know what is true anymore? How do I know who to believe?

That is a very difficult question to answer. Almost everything in our current economic and social system is sponsored or supported by a certain agenda or viewpoint on the world. It’s very, very difficult to know what to believe.

I find it useful to think about the following questions when I come across a climate policy or suggestion:

- Who is behind the idea? What is their experience – are they an ecologist, an economist, a physician, a politician, a doctor…? Does this experience relate to the proposition they are making?

- Who finances this person, or this organisation? Are they sponsored by big business, wealthy entrepreneurs, Jeff Bezos/Bill Gates…?

- Where was this research or policy produced?

- What happens when I perform an internet search on this idea? Or on ‘criticisms of x…”? Are there strong counter-arguments to it?

The other thing to keep in mind is that there is no ‘true’ solution to climate change. There isn’t even a ‘solution’ to it, because the problem is so complex and so widespread throughout societies across the world that no one mechanism or set of policies will enable us to respond adequately.

Conclusion

What have we learned about the ultra-rich? That their class interests (money and power) and their climate anxiety (about losing these things) have encouraged them to act in a coordinated manner to impose a certain narrative of climate change and climate solutions.

Morena concludes his book: “They may talk to us, feigning emotion, about apocalypses, collapses, a burning planet and the point of no return, but their climate emergency is not our emergency, and even less so that of the vulnerable populations already hit by the effects of global warming. It is the rich who are destroying the planet.”

It’s important to highlight this point: “their climate emergency is not our climate emergency.” Their reasons for fear, the things they will lose, and the things they want to protect are not the same as the majority of people on this planet. And when we understand this, we understand why they believe that market mechanisms and technological inventions will save us from climate collapse. The market mechanisms are in place so that they can continue to generate wealth from their investments, and the technological approach enables them to build a future where they retain their power.

Morena writes, “The climate policies implemented for their benefit – based on tax breaks, tax credits, guaranteed loans, public/private partnerships, voluntary commitments and market mechanisms – come at a high price for society. As well as being ineffective, they unfairly place the financial risk and cost of transition policies on the community.” Instead of helping address the climate crisis, these policies put the cost of a society-wide ecological transition on the community, rather than on those who are most responsible for the destruction of living ecosystems, the loss of biodiversity, and the changing climate.

You could be part of an ecological transition where you will become happier, wealthier, and more connected to other people and to the planet. These carbon credits and technological solutions will in no way benefit you in the long term. They are mechanisms designed by those who have power and money, so that they may continue to have power and money as the climate changes and their investments and assets are threatened.

I agree with Morena’s conclusion: End of the world. End of the month. End of the ultra-rich.

They are the same battle. Climate change, poverty, and inequality are three sides of the same problem. They certainly won’t be solved by more of the same thinking that created them.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024