Big questions: Economics

What actually happens in the economy? And how do our representations of the economy influence the way we try to solve the problems that we have identified? Are there alternatives to this dominant neoliberal paradigm, which isn’t working? These key questions will be answered here.

New Zealanders have just elected a new Government for the next three years, led by the National Party. As Toby Boraman remarked on The Conversation and RNZ, “Labour out, National in – either way, neoliberalism wins again.” The orthodox and dominant economic thinking in New Zealand has for some time been neoliberalism. In 2021, Branko Marcetic wrote an article for the Jacobin entitled, “The New Zealand “Socialists” Who Govern Like Neoliberals” with exactly the same message: New Zealand’s political parties, and the economists that support them, might claim to wear different colours, but underneath they’re exactly the same.

This isn’t the case everywhere in the world, although dominant economic, scientific, and technical thinking is becoming more prevalent in many countries. Markets, competition, free trade, and cut backs vs spending are not the only way to look at the economy. Nor are they the only instruments a government has at its disposal to respond in times of need.

Liberal economists and financial markets

In 21st century western societies, economists are constantly making predictions and analysing the forces of the market, in order to determine what our lives will be like. You would be justified in thinking that these market forces, in particular the financial markets, are the direct determinants of the wellbeing of our citizens.

This is only partially the case. Whilst financial markets have become some sort of ruling deity for governments and businesses, where every decision is calculated so as to not displease these markets, they are not the only way to look at the relations between people in a society. I’m sure you’ve heard yourself referred to as a consumer, and those companies who make the things you buy as producers. You exchange money and goods with them inside a market, and this forms the basis of the relationships you have, besides those with your family members, as an adult in society. There are, however, other relationships going on, and other exchanges being made, which are also economic in nature, but which are not best carried out in this model of a free market.

New Zealand suffers from a hegemony of orthodox liberal market economists. All Finance Ministers believe almost the same things about the economy: as demonstrated by the two articles linked above. What differs is the extent to which they want to intervene through social subsidies and Government spending (and therefore in taxation, too). Left leaning parties tax to redistribute some of the wealth; right-leaning parties reduce taxes to let the market decide. But, the major players of the economy, the belief in the market, the possibility that the market will make corrections, and GDP as the holy-grail are common amongst all of these economists.

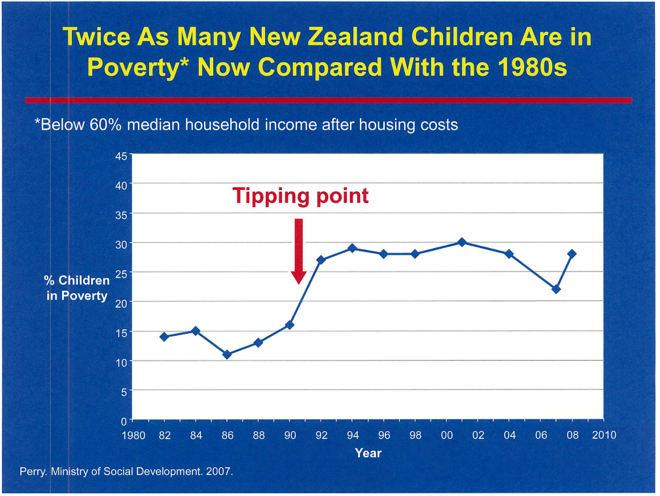

For many, many years, the Government has talked about poverty, illiteracy, a housing crisis… and none of these issues have been resolved. Looking at the child poverty statistics released by StatsNZ, many of the indicators have barely changed since 2007. This shows the limitations both of the economic instruments being used, and the representation that politicians and economists are using to understand the problem. As we will see, there is more than one way to look at the economy, and the exchange relations that are going on between people each and every day.

The ecological crisis is yet another crisis that will almost certainly bring our current economic system to its knees. Based on our collective ability to act in the face of current problems, which seems very limited, it is rational to be worried that we won’t be able to confront this crisis either. If we’ve been largely unsuccessful at responding to the social crises of the early 21st century, the ones coming up will be even worse, as it becomes harder to produce fruit and vegetables, more and more property is destroyed by climate disasters, and social relations and mental health decline further.

The four representations

Gilles Raveaud, in his book Les Disputes des Economistes (the Disputes of Economists, 2013), refers to four main representations of the economy. These are:

- The market, for liberal economists

- The circuit of money flows, for Keynesian economists

- The place of power struggles, for Marxist economists

- A part of nature, subject to its limits, for ecological economists.

Each approach points towards a different way of looking at the economy. There are problems with each theory, there are benefits to each theory. But they are just that: theories that attempt to explain the world. The world in which we live constantly changes, so we cannot believe that one model will always be the true representation of reality. Raveaud’s analysis is particularly useful to see the differences between economic theories. The economic representations below synthesise his book.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Discover the economic representations below.

Liberal Economics

For liberal economists, all economic mechanisms such as labour, health, education, and welfare, are viewed as markets. The goal for these liberal economists is to increase competition within these markets, which will drive down prices and increase the quality of the goods and services provided. Government plays a small role, because the markets know how to regulate themselves.

Adam Smith, Scottish economist in the 18th century and author of “The Wealth of Nations,” believed that wealth was created through exchange. As individuals, we must sell our labour, in order to be able to buy the things that we need. We do so in a market for labour, just as there are markets for fruit and vegetables, meat, technological devices, and construction services. The market, for Smith, is a place of freedom, creativity, and autonomy for each person, and the market is like the social cement between individuals. Our social agreements are not based on emotions or tribal organisations, but rather on the free exchange of goods, services, and labour.

Markets are regulated, according to the liberal economists, by something called the price mechanism. The price of a particular good, for example one kilo of kumara, is determined through negotiations between buyers and sellers. If the price of kumara is set at $1 per kilo, everyone will want to buy some, and the supermarket will sell out by 11am. All the people in the afternoon will not be able to buy kumara. On the other hand, if kumara is $10 per kilo, there will still be some left at the end of the day, because only a few people wanted to buy it at that price. The seller sets the price, and the consumer responds, and in a movement like this, they find the best price where the greatest number of people can buy kumara at the highest price for the seller.

Is this price, established through ‘feedback’ between shoppers and the supermarkets, fair? Liberal economists would say yes. If the market determines that the price should be $7 per kilo, some people will miss out. These people are happy, according to liberal economists, because they preferred not to buy kumara – they made the choice not to. Everyone is content, because everyone made the choice of what they would buy, based on how much money they had to spend. But, this price is only fair if all the shoppers are there to negotiate with the kumara growers, which is never the case. Likewise, the shoppers must know about all the other supermarkets selling kumara, too, before making a fair choice. They might be selling it cheaper elsewhere, but we rarely shop around all the stores before deciding what to buy.

In good times, this price regulation seems alright: we get lower prices and better quality due to competition; people are all choosing what they want from an open and fair market. However, as we are feeling now with the 2023 cost of living crisis, and have felt for some time, in periods of crisis, people are not happy about the choices they are forced to make. Likewise, good and bad choices become polarised, especially in the case of markets for education and hospitals – some hospitals are labelled ‘good’, and others, ‘bad’ or ‘dangerous.’ In times of crisis, it is impossible to find the ideal point where shoppers and suppliers are happy, at the right price.

Keynesian Economics

John Maynard Keynes realised that in times of crisis, the market could not work by itself to sort things out. During the Great Depression of the 1930’s, Keynes challenged the viewpoint which said that people selling their labour (workers) and people buying that labour (entrepreneurs) would end up balancing out such that all those people who wanted a job would have one. Instead, unsold goods and unemployed people are not the exception, but the norm of market economics. Left to its own devices, the market will self-destruct. Therefore, we need certain powers of direction for the market, so that it goes in the right direction.

Instead of looking at the economy in terms of markets, Keynes thinks it’s better to look at it like a circuit. In this circuit, money flows between people all the time. Money has no value of itself, but because we all believe in its value, money holds importance and meaning. When banks lend people money, despite the fact that they might only have $100 in their vault, they can lend around 10 times that much – $1000 – to someone wanting a loan. At no moment in this transaction is money actually used – the loan involves moving numbers from one ledger (that of the bank), to another (that of the borrower). This system works if there aren’t too many loans, and if not everyone wants their money at the same time.

Entrepreneurs are rational people for Keynes, and it is their movement of money which constitutes the greatest activity in the economy. When entrepreneurs reduce their prices, they are able to sell more. But in order to keep lowering their prices, they either have to reduce their wages, or their profit margins. This leads to unemployment, and very easily, a negative spiral can start, where prices reduce, wages reduce, unemployment increases, and the market cannot find a solution.

Another actor is needed in order to correct this problem, according to Keynes. These actors take the form of institutions: either the government, or the central bank (the Reserve Bank in New Zealand). The central bank can change the interest rate, which will either increase or decrease spending. When money becomes more expensive, people spend less of it, and vice-versa. But, with this option, we can very easily end up with inflation: when the price of everything increases.

On the other hand, the Government can also act by spending money in the economy, in the form of construction projects, welfare payments, health and education, subsidies, and more. This money will then flow through the economy, and enable wages to increase again. However, there are leaks to this circuit of money that Keynes has imagined. Companies can choose to save the money they are given by the Government, instead of spending it. Some consumers will spend this money on goods from other countries, so the money leaves the country and is not seen again. This strategy also increases public debt, the amount of money that the Government has borrowed.

During the COVID crisis, these two strategies were used by the Government and the Reserve Bank to manipulate the economy, because the market by itself was not able to regulate itself. The Government spent a lot of money during the crisis, giving it mostly to businesses, so they could stay alive despite not trading. But, this spending led to inflation, as all the prices increased. As a result, the Reserve Bank increased the price of money, the interest rate, which meant that it became more expensive to borrow money, and spending will therefore decrease again. This decrease in spending, otherwise called inflationary pressure, is felt most severely by the lower and middle classes of the economy. It becomes noticeably more expensive to just buy basic goods, especially when wages are not increasing.

The problem with Keynesian policies is that they increase public debt, and they very often don’t work well unless there is a coordinated approach or strategy at a higher level, because of the leaks in the circuit. What we have seen, however, is that there are power imbalances in the economy which are not able to be addressed by the market, or by Keynesian institutions.

Marxist Economics

When the buyers and sellers have decided on a price for kumara, some people will miss out because the price is too high. Liberal economists justify this, saying that these people, on low incomes, are happy with not having any kumara, because they decided not to buy any. Karl Marx, a major thinker in 19th century political economy, and analyst of capitalism, argued that liberal economists are just justifying the impoverishment of low-income earners. Marx was a key thinker in the development of socialism, and what we know today as worker’s parties such as the Labour Party.

According the Marx, the economy is the place where power struggles play out. In the capitalist economy, a limited number of people own the means of production, which are the factories, office blocks, machines, agricultural land, etc. The rest of the population are workers who are forced to sell their labour to these few, in order to live their lives. Because there are always unemployed people on the labour market, wages very often do not increase: if a worker wants to be paid more, the company can fire them, and instead hire another person who is willing to be paid less. Wages are therefore fixed by the market, and not in terms of the value produced by a particular employee in their work.

The capitalist, the one who owns the means of production, buys the right to use the labour of a worker for a whole day, by paying them a wage. This work therefore belongs to the capitalist, and not to the person who did the work. For example, someone working as a data analyst does not own any of the data analysis that they do. This person spends their entire day producing things that will not belong to them. In this way, workers are exploited, because they are not able to obtain the value created by the work that they do. Instead, the company sells the data analysis and pockets the profits, for example.

Marx disagrees with Adam Smith, who we read about before. Smith believed that wealth was created through exchange, but Marx believed that it is violence that creates wealth. The domination of one person or resource by another is what leads to this person becoming rich. For example, it was through stealing land, slavery, and the expropriation of villagers that the British Empire was able to amass power and wealth in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The global economy is, according to this analysis, not to everyone’s advantage. What ends up happening is that some people control a lot of the machines, land and buildings necessary to produce goods and services, and these people are concentrated in wealthy countries like the United States. Multi-national companies like Apple, Toyota, Nestle, etc. capture most of the value added, and the workers, often in Asia, of these companies, see almost nothing of what the company rakes in when they sell their goods. The market is, for Marx, hierarchical and a place of domination, and not a place of freedom and expression as Smith believed.

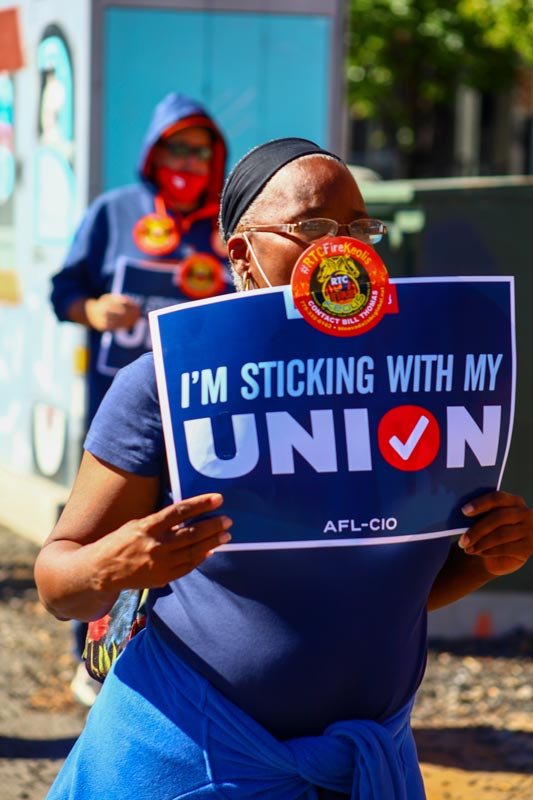

For liberal economists, freedom is about being able to possess, to exchange, and to sell things. Democracy is therefore about being free to do these things in the market, without much intervention by a government or external actor. However, in a capitalist regime motivated by profits, socialists argue that there will be too many cars, robots, televisions and soft drinks, and not enough social housing, schools and hospitals. These public goods, such as health and education, need to be provided by the Government, so that all citizens are assured a quality education and healthcare regime, no matter their position or actions within the market.

In the early 21st century, many previously state-owned services were sold off to private buyers, with the idea that increased competition would improve the quality of services provided. However, this was often to the detriment to the employees of these companies, as well as services often being cut, reduced, or unreliable, such as what happened with the rail network in the United Kingdom. Sometimes, the private market suppliers collude – they make an agreement to keep prices high – and this is in their interests, rather than in the interests of the people consuming the service. This has been shown to be the case with electricity markets in Europe, with petrol markets, and more.

Today however, the market for goods and services is not the largest or most dominant economic market. That would be the financial market. In the 1970’s, the financial markets were opened, and currency exchanges were no longer made at fixed rates. Buying, selling, and lending on the financial markets increased dramatically. Whereas previously, paying people a salary meant that you were guaranteeing that they could buy your goods, now, this is no longer the case. Wages are a cost, rather than a guarantee of consumption, and therefore, they must be reduced as much as possible. The money that is used to buy things and to invest, in large part comes from these financial markets, and not from the sale of goods and services.

In the end, according to Marx, the exploitation of workers is what will cause the demise of capitalism. This is because the only way to make profits is through taking the added value of the work that employees perform. Value is created through labour, and exploiting this labour for the benefit of the few at the expense of the many. At a certain point, however, these workers can no longer buy the goods and services that they are busy producing, because they no longer have enough money for them: most of it is concentrated at the top. Capitalists can do nothing about this: they are forced, by competition, to keep making a profit, by reducing the prices and selling more, or by reducing the costs of production (the price of labour, the wages). This leads to overproduction, and so food and other goods are wasted and destroyed because they are not sold. People go hungry and starve, yet companies are overproducing the things they need to survive.

This situation, to Marx, is completely absurd. He believed, therefore, that capitalism is a very inefficient economic system, and should be replaced by something else, or strongly domesticated. If Smith believed in no intervention in the economy, and Keynes believed in some intervention, Marx believed in a lot of intervention, or just removing the whole system. Smith’s economy based on free association between people is criticised by Marx, instead believing that the economy is based on relationships of domination between people. Both economists believed that economic growth is a good thing, however.

Environmental Economics

However, as industrial economies began to produce more and more waste, and it became evident that human beings were having a strongly negative impact on their environment, the dogma of economic growth began to be brought into question. Karl Polyani was an environmental economist, and author of “The Great Transformation.” He saw the economy as a system of work embedded within nature and our environment. Polyani was against the idea that the economy should be organised or thought of in terms of markets and exchange relations. The idea that a market could regulate itself, and that prices would be established fairly by the market, was ludicrous.

The result of this market thinking is that all spheres of human life have been absorbed by market economics, replacing relationships of care and solidarity by the exchange of money for services offered. The exchange relation is the most risky and unstable, according to Polyani, because there is no underlying principle guiding behaviour. Each person is therefore pushed to fight for their own self, and becomes egotistical and self-interested.

For Polyani, labour, land, and money are not goods that can be commodified and bought and sold in a market. Labour is just the work of human beings, land is that upon which human societies exist, and money is a creation of the central bank. None of these things were created to be sold in a market: they are the very fabric of the economy itself. Whereas Marx believed that the power struggle between the capitalists and the workers was the source of the problem and its solution, Polyani believes that it will be the recognition of the needs of the society and its relationships that will bring an end to the domination by exchange relations.

Exchange relations are not the only way of organising a society, according to Polyani. We also have relations based on reciprocity, and on redistribution. Reciprocity considers the other as equal to oneself, and therefore seeks to give in equal terms for what is taken. Redistribution requires a central authority which will take the resources from some people, and give them to others, so that each person is considered equal. Market-based relations treat human beings as instruments, as a means to obtain what one wants, rather than having a value in themselves. The solution, therefore, is to restrict or reduce the exchange relations that we have in our lives.

The dogma of economic growth is another aspect of economic thinking which Polyani strongly criticises. Whilst strong economic growth led to huge gains in the standard of living for many Western countries, this growth also created major social and environmental problems. These include pollution, reduction in working conditions, people becoming more individualised and an increase in violence, the production of useless and quickly obsolete goods, advertising everywhere, without limits, and more. Economic growth is measured in terms of the increase in GDP, the gross domestic product, which is the sum of the value of all the goods and services produced in a country within a certain time period. However, this measure doesn’t take into account the social and volunteer work that produces value, nor does it account for the environmental impacts of economic activity. GDP also isn’t able to measure inequalities in a society, yet takes into account ‘bad’ activities – GDP increases when more people are buying paracetamol, whether they really need this or not. It is therefore severely limited in what it can measure. Using a very limited measure of value as the single most important determinant of the ‘health’ of the economy, is, therefore, quite restrictive.

Despite this, most economists today, liberal economists, are searching for continuous economic growth, believing that this will lead to better lives for all people. In fact, GDP increases produce greater satisfaction up to a point, at which happiness no longer increases in the same way, despite increasing GDP. The United Nation’s World Happiness Report demonstrates this. You can read more about how happiness is challenging GDP as a measure of health in this article on The Conversation.

Nicolas Georgescu-Roegen, a 20th century economist and mathematician, believed that economic value was not created through markets or exchange, or even through labour, but through the natural resources which are taken and transformed. The current economic system takes natural resources with value, and spits out waste, with no value. Using the laws of thermodynamics, Georgescu-Rogen explains how humanity, and the economy as the transformation of natural resources, cannot continue to grow infinitely. Endless economic growth is not possible, with the materials and resources we have on earth. He points out that it is as if human beings decided to have a brief but exciting existence on planet Earth: each car we produce means fewer human lives will be possible in the future.

There is another type of economy which environmental economists propose. One part of this involves ‘de-growth,’ which is the idea that we must shrink the economic action occurring in the economy, or at least, no longer care about the idea of growth. Tim Jackson is a British economist who promotes this idea. Another pillar is a kind of “Green New Deal” which proposes government investment in renovating and insulating housing, converting fossil fuel electricity to renewables, developing public transport, sustainable agriculture, and more.

Finally, growing the social economy, or social enterprise, is another part of the solutions these economists propose. This means more people will have jobs that are meaningful, in which the value that they produce goes directly to people who need it, and each person in the value creation chain is valued equally. This social economy is not founded on the principle of competition, rather it is based on cooperation between self-organised individuals.

Explaining crisis

To review these theories, let’s think briefly about what they say about how crises come about.

According to liberal economists, intervention in the market is what causes problems. This is what ACT and National have been telling us for some time: the Government itself is the problem, it’s intervening where it should not which is causing problems.

The Keynesians and Marxists would say that this is not the case. In fact, the market economy is essentially unstable. Marxists want to control, regulate, or abolish financial markets, to solve these problems. Keynesians point towards making investments in the society to correct this instability.

The environmental economists point to the instability and unsustainability of the current model of extraction and economic growth. It is this that causes crises: increases in the price of necessities such as petrol, food and housing make it more difficult for people to live. These increases are written into the code of the current economic order, and are therefore inevitable. Like the Marxists, we must change our economic system if we are to solve the problem.

To conclude...

Environmental economics is a field of study which is not widely accepted yet. Concepts like degrowth and a Green New Deal are not mainstream ideas, but remain with a few thinkers and economists, mostly in Europe and the United States.

New Zealand economists consist almost entirely of liberal economists, who believe that markets can and should run themselves. Neoliberal thinking is that which accepts some role of the state in providing certain services, and in arranging conditions of competition such that the market can operate. With this lack of economic diversity, it is easy to fall into the trap of these economists, and believe that the only solutions are the ones that they propose. Economics is not a science, but the use of human-generated representations in order to explain economic activity in societies.

As we have seen, there are other alternatives. There is also an enormous possibility to develop an environmental economics which rests upon principles from Tikanga Māori. The so-called “Māori economy” currently refers to economic activity carried out by Māori organisations, but if more Māori decided to become economists, and to develop their own representation of the flow of money and resources in the country, they could very easily develop their own economic theory.

Economic perspectives overview

Liberal Economics | Keynesian Economics | Marxist Economics | Environmental Economics | |

Main theorist | Adam Smith | John Maynard Keynes | Karl Marx | Karl Polyani, Nicolas Georgescu-Roegen |

What is the economy? | The markets for goods and services | A circuit where money flows | The place of power struggles | Human activity embedded in nature |

What produces value? | Exchanges of goods and services in the market | The flow of money through the circuit | Violence – domination/ exploitation of workers | Natural resources – land, plants, animals |

Key problem to solve | Interventions which stop the market from self-regulating | The flows of money are not well distributed | Workers are dominated by capitalists and do not earn the value they produce | Market relations have commodified everything, and infinite growth is not possible |

Solution | Make sure markets function by increasing competition and removing barriers | Intervene in the market with economic instruments – interest rate and govt spending | Abolish capitalism and allow workers to own means of production and receive value of their work | Develop the social economy, reinstate redistributive and reciprocal relations, degrowth, fix environmental problems and waste |

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.