author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 07/02/2023

- No Comments

- Politics

share

A miraculous solution to stop waste production and lead sustainable lives, or a grand delusion which doesn’t actually work, and simply justifies keeping the status-quo approach?

The idea of a circular economy is not a new one. Waste and the offcuts of human activity have been used and reused for millennia – and the old saying “one person’s waste is another’s treasure” has continued to circulate in our everyday language to resurrect this idea. In the third decade of the 21st century, however, we are beginning to see the circular economy becoming a larger-scale project both in business and government, who claim that this is the solution we need to be able to transform our economies to combat climate change and the wider ecological problem.

At its most simple, the circular economy is an exchange of goods and services in which waste is minimised, and things are recycled and reused as much as possible. Think of it like glass bottle recycling, but on a massive scale. Our phones, washing machines, t-shirts and sports shoes should all become a bit like the glass bottles: recycled and transformed into other products that we can use again.

On the face of it, this might seem like a great model for the economy. After all, we know that waste is becoming a major problem for many countries across the world, as we consume more and more goods made of synthesised materials such as plastics, cotton and polyester mix clothing, electronic devices, and more. A zero-waste economy, therefore, would seem to solve the problem we are having with waste and pollution, and help us to reduce our environmental impact.

However, as we will see, this is a nice idea that simply doesn’t work in the biosphere. The assumptions used by proponents of the circular economy are often misguided and uninformed, meaning they go against fundamental principles of life on Earth. And from an economic point of view, the circular economy is based on a very big hypothetical statement – a very big IF – that as we are seeing, is proving not to be the case.

Let’s delve into the circular economy, to see what lies behind this big idea. We’ll start with the arguments from those who support the circular economy, and then look at the critiques.

In support of a circular economy

The New Zealand Government seems to have also adopted the idea of a circular economy, ōhanga āmiomio, along with much larger international bodies like the European Union, as a way of managing waste, saving money, and encouraging jobs and innovation.

New Zealand also has various organisations working in what they call an “ecosystem” (we’ll think about that terminology later!) of circularity, including Circularity.co.nz and XLabs. There is also Āmiomio Aotearoa at the University of Waikato, with around 50 researchers looking at the circular economy.

Their main point of reference is the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, an organisation set up by scientist Ellen MacArthur to promote the circular economy on a global scale. On the site, we see that there are three key pillars to the circular economy:

- Design out waste and pollution. This means that we create a zero-waste economy. We are no longer polluting rivers and streams, no longer emitting large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases without compensating for our emissions, and we are certainly not sending large truckloads of materials to landfill or incineration.

- Keep products and materials in use at their highest value. Everything that we extract is used, all materials are reused and recycled, and nothing is simply left and abandoned as an unusable resource. An old pair of shoes could be made into a sports ball and a t-shirt; a broken table could become a fence…

- Regenerate natural systems. This is through the use of renewable energy sources like hydro power, solar power, wind energy, etc., as well as actions taken to actively restore unproductive soil, polluted rivers, and take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

These three principles, according to the Foundation, are inspired by nature, and by natural cycles. Nature works in a complete loop, apparently, and materials are constantly recycled and put to a new use.

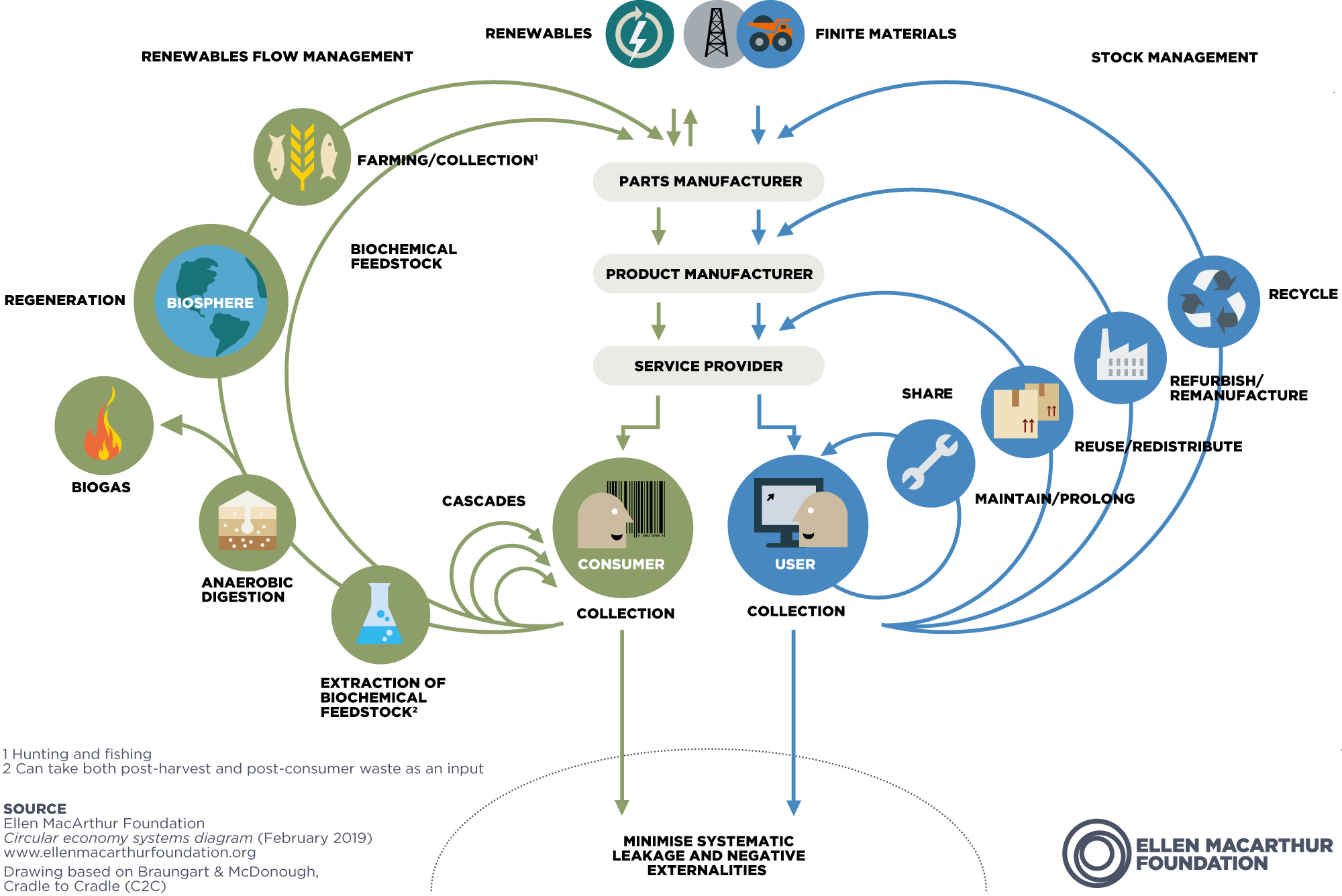

The Foundation has designed the above butterfly diagram to explain how the circular economy works. We see that we minimise both the inputs into the system, and the outputs or waste that comes out of the system. We also see that both natural cycles in the biosphere in green, and human-created cycles in the technosphere, or the economy, in blue, are part of our circular economic system.

The economic arguments

The circular economy aims to “gradually decouple economic growth from virgin resource inputs.” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation). This means that they want economic growth to become independent from the natural resources that flow around the economy. In essence, the economy can grow and continue growing whilst we are on a planet with limited resources. How do they think that is possible?

The answer comes from Nobel-prize winning economist Robert Solow. He gave a conference lecture entitled “The Economics of Resources or the Resources of Economics” in 1974, laying out his ideas on resources. According to Solow, the reason why we have economic growth is not because of more capital, or more labour inputs. Capital and labour are considered the two factors of production in neoclassical economics, which determine the nature of our production systems. Instead, economic growth is due to technical improvements – the economy grows because we become more efficient at exploiting resources and more powerful in our technological capacities. We can get more done in less time, spending less money doing it.

In the case of the market for natural resources, Solow writes that, “If flows and stocks have been beautifully coordinated through the operations of future markets or a planning board, the last ton produced will also be the last ton in the ground. The resource will be exhausted at the instant that it has priced itself out of the market.” This exhaustion of the resource – meaning that we’ve used every last drop of oil in the ground, for example – is not a problem for Solow. This is because the market will know that we are approaching extinction, and begin to develop technologies that are able to replace this natural resource. As the natural resource becomes scarcer, it will become more expensive. In turn, the synthetic resource will become cheaper, and more widely used. The “invisible hand” of the market, or a central planning board, will govern all of this such that we can just keep going, despite having used all the oil, coal, gas, rare metals, wood, etc.

Here’s the key quotation in full, that you will often see cited in discussions of Solow’s economics:

“If it is very easy to substitute other factors for natural resources, then there is in principle no “problem.” The world can, in effect, get along without natural resources, so exhaustion is just an event, not a catastrophe. If, on the other hand, real output per unit of resources is effectively bounded—cannot exceed some upper limit of productivity which is in turn not too far from where we are now—then catastrophe is unavoidable.”

Therefore, because technology will help us to replace natural resources, we don’t need to be worried about running out. The economy can and will continue to grow because growth doesn’t depend on material inputs, but on technological advances.

Solow assumes that we can replace natural resources by technological resources as perfect substitutes. If this is not possible, Solow knows that we are heading towards unavoidable catastrophe. Many accounts of his economic viewpoint will only provide the first half of this quote. We should keep in mind that Solow was not ignorant towards what he was proposing, and the consequences if it turned out not to be true.

Finally, let’s think again about the benefits of the circular economic model. If we’re not producing waste, then we will no longer be polluting local ecosystems, nor the biosphere in general. This will have a positive effect on the environment: ecosystems will be able to regenerate, less greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will stop global warming, and more. Additionally, when materials are reused and recycled, rather than simply purchased again, we require people and skills in order to undertake these repairs and manage the recycling systems. This will create jobs in the economy, and stimulate innovation in order to find new, cost-effective, efficient ways of reusing and recycling materials in the economy.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Critiques of the circular economy: Back to reality

If we were living in a bubble outside of this Universe, the circular economy would be wonderful. The problem is, we’re on planet Earth. The economy doesn’t exist outside of the chemical and physical laws that govern our universe. We human beings don’t live outside of these natural cycles either. Let’s see why the idea of a circular economy is just an illusion. Reading these critiques, we should be worried that the circular economy is gaining so much ground as a real project to be implemented. As Keith Skene from the Biosphere Research Institute in the UK wrote in 2017, “almost all of the principles underpinning the circular economy have the potential to destabilise the biosphere if they are applied in the real world.”

Circles don't grow

Have you ever seen a closed cycle that, by itself, gets larger and larger? I certainly haven’t. If we really had a circular economy, the same things would be going round and round, being transformed and retransformed again and again. This, however, doesn’t equate to growth as we were promised. The only way to achieve that growth would be to think of the economy as a spiral, going round and round, but at the same time accumulating more and more so that the spiral grows bigger as time goes on. On the metaphorical level, a circular economy in which growth happens is not possible: circles don’t grow. Machines and technology might become more efficient, but they need more and more energy to run, and they require some material resources to be produced in the first place.

The supporters of the circular economy claim that this circularity is influenced and inspired by nature, and natural systems. According to them, nature is a zero-waste system, and so we should try to mimic nature and do the same. They believe that the Earth, and therefore the biosphere, is a closed system in which energy in the form of matter circulates constantly. Skene writes of this idea of nature: “Referencing nature is any attempt to justify zero waste, eco-efficiency, optimisation or circularity is, at best, misleading. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

In fact, the biosphere is an open system. This means that it requires inputs, and has outputs. The largest input into the biosphere is solar energy coming from the sun. Life in the biosphere tends towards increasing complexity. As the biosphere becomes more complex, more and more sunlight energy is required from the sun for this system to be maintained, and to increase again in complexity. This natural system is not efficient, either. The biosphere converts free energy into waste energy – that’s what life is and does here on planet Earth. Nature, in fact, is hugely wasteful. It most certainly isn’t optimised, either. In complex situations, fast recycling is favoured over durability, sustainability, optimisation and use of resources, and many other supposedly natural variables. You will not find an ‘optimised’ natural system.

XLabs claim to be able to teach their participants about nature: they talk about “Mirroring nature to radically redesign the system for optimal resource use.” A zero-waste economy is simply a fiction. The mere fact that we, human beings, are biological creatures in the biosphere, means that we will continue creating waste for as long as we exist. The economy will continue producing waste, because this is how the universe functions. Optimisation and nature do not fit in the same world.

Humans and the biosphere: inputs and outputs

The third pillar of the circular economy is the idea that human economic activity can contribute to the regeneration of natural ecosystems, or at least keep these natural systems working at their highest utility and value. The diagram of the circular economy has two sides, depicting two cycles, which are interrelated, and which human beings would therefore need to manage and control, under the name of economics.

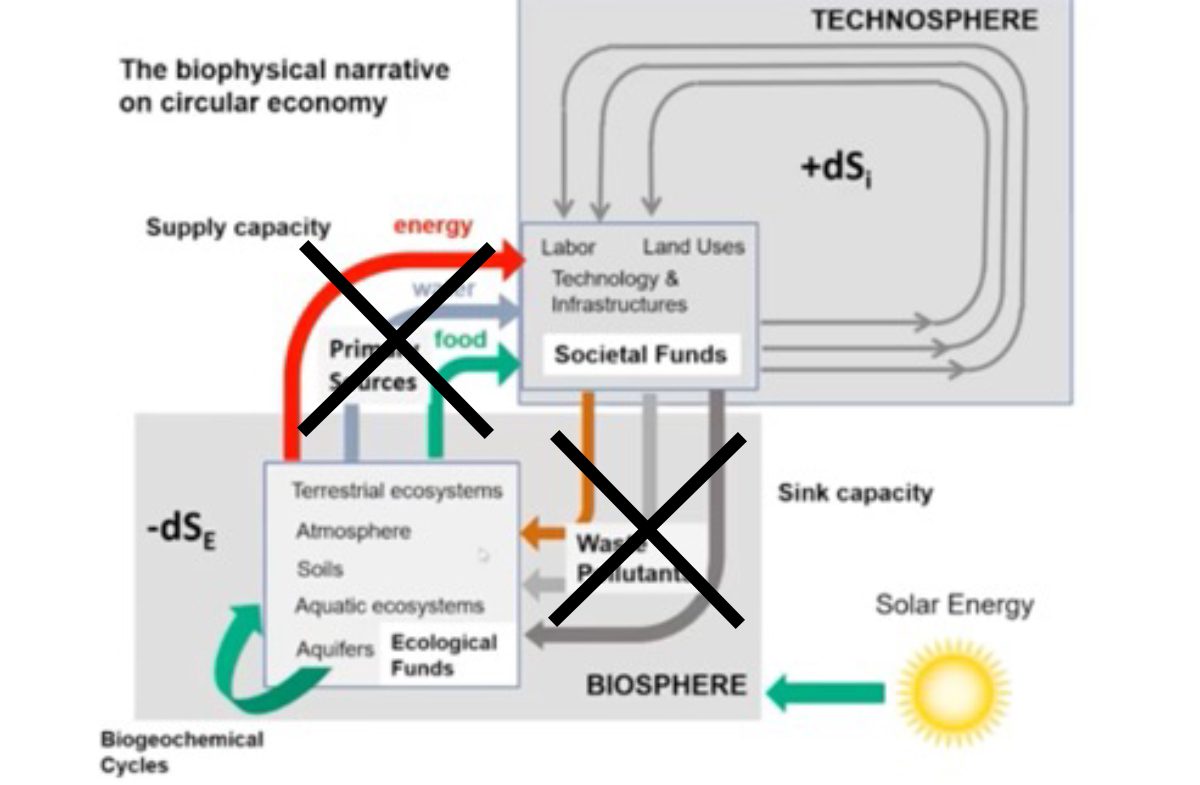

According to Mario Giampietro, at the University of Barcelona in Spain, and many other thermodynamic scientists, the circular economy takes no notice of the directions of material flows in the economy. They measure the flow of money, and therefore the flow of goods and services, but not natural resources, energy, water, and other elements which flow through the biosphere and interact with the technosphere (the sphere of human activity).

Natural cycles require absolutely enormous amounts of energy. Giampietro makes a revealing comparison: in 1999, human beings required 11 TW (terawatts) of energy for all their needs. Just for maintaining the water cycles around the Earth, the biosphere used 40,000 TW of solar energy in one year. When we look at the diagram of circular economy designed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, we see natural cycles on the left and human cycles on the right. In actual fact, if these arrows and circles represent energy flows, the human cycles would be infinitesimally small in comparison with the natural cycles. Nature has huge amounts of energy coming into it from the sun, and huge amounts going out as waste, too. Such a model would lose all sense of ‘circularity’ that seems crucial to the idea of the circular economy. There is definitely not a closed system of nature as XLabs seem to promote – there are simply not enough energy sources on Earth for this to be possible.

Let’s also think about the flows of water. In Europe, it is estimated that 7,500kg of water per day is required for agricultural needs of one person. This doesn’t include urban water usage, or industrial water usage. Just the water used by plants and animals that sustain the life of this human. When water is not included in the economic calculations, 35% of the European economy is recycled. It seems possible that we can end up with a 100% recycled economy – a circular economy. When we include water, however, which is not recycled by us at all, but rather through natural systems, we end up with 0.005% of the economy which is circular. If we included energy flows, raw materials, and all the other natural cycles, we would end up at almost zero percent recycling rate. We create waste, in far greater quantities than we would ever be able to recycle what we use.

The idea of the circular economy is to therefore cut out two central pillars of the biosphere – inputs of energy, and outputs from human waste back into the biosphere, as is shown here. This is nonsensical, akin to proposing to sell computers where the wires to charge the battery with are cut, and the wires to illuminate the screen are also cut. Inputs and outputs are avoided, so that the computer can function in a circular way. The company would be bankrupt before their product even went to market: nobody would even invest in their idea. Zero-waste, zero input circular economies are physically impossible.

Back to the economic argument

Remember that Robert Solow claimed that we could get along fine without natural resources, because technology would just replace out these resources with other goods? Let’s put that claim under the microscope. When we use all the rare earth metals, what will we make more solar panels with? More electric cars with? When we use all the fresh water, what will we drink and feed our plants with? When all the soils are destroyed, what will we grow our plants in? What will animals live off? Will technologies really be able to solve all these problems in the next 30 years?

We cannot live without natural resources. The economy cannot “get along without natural resources.” To grow plants we need soil, and the way soil regenerates is so complex that we are yet to understand it. What we know is that when we use ammonia and nitrogen-based fertilisers to optimise the soil over one or two growing cycles, we kill all life in the soil and it becomes dead and unproductive. We can’t get by without soil, and the only way to have healthy soil is to promote biodiversity on the land, and not to use technologies that make this soil more efficient, such as ploughs, and artificial or even ‘natural’ fertilisers. Further, we cannot ‘produce’ productive soil, the only soil that will be productive is that which is on the Earth and is there now. For a great first-person account of the impact that these technologies have on soil and the farming system, read English Pastoral by James Rebanks.

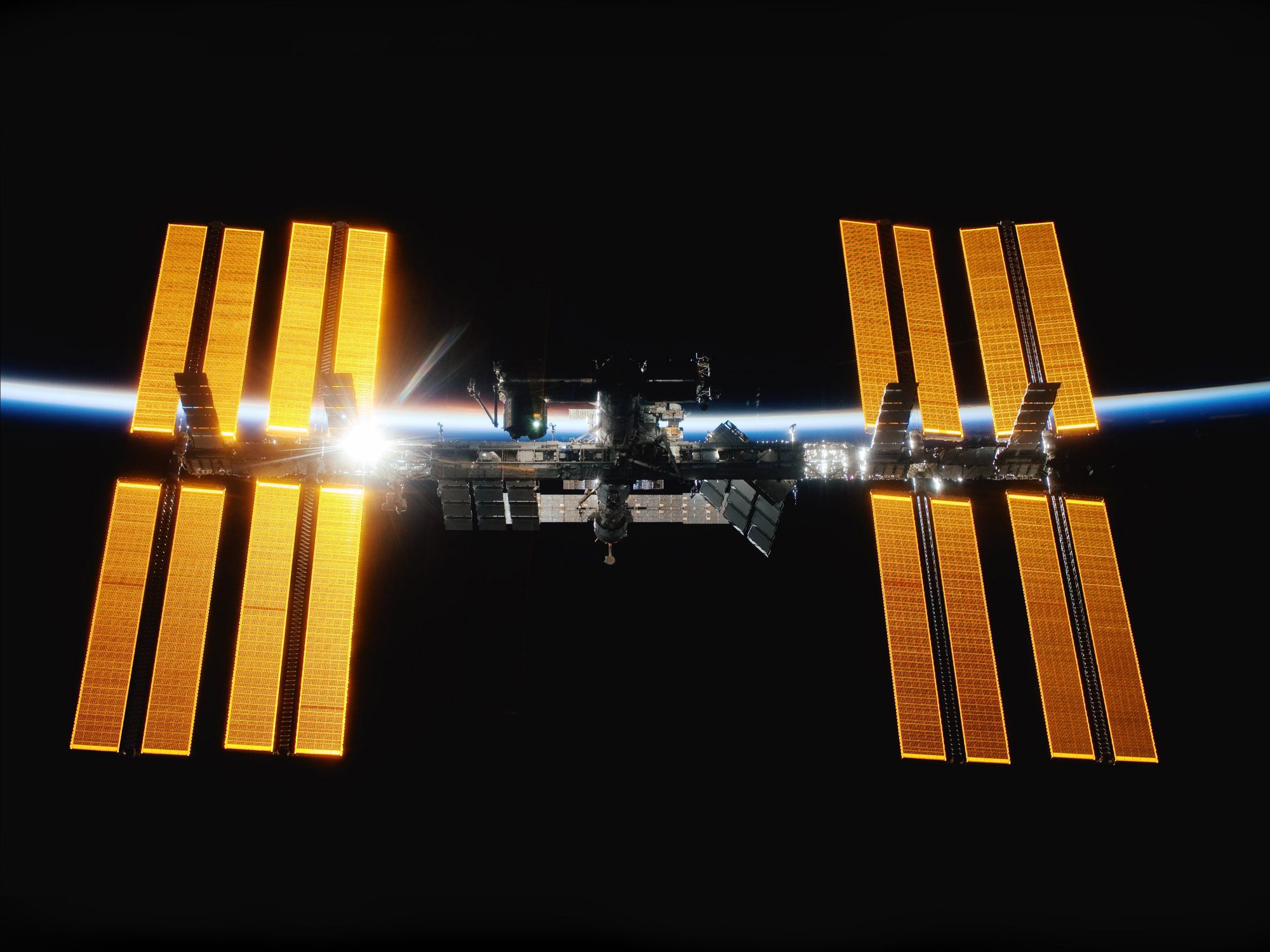

We also cannot live without waste and without inputs of energy and resources. The International Space Station is perhaps the best example of human engineering of a standalone climate-controlled system, and even there, they still require food to be sent up, and eject waste out of the station regularly. We simply cannot replicate all the functions of the biosphere by ourselves.

Therefore, the only option left to us by Solow is a complete catastrophe. And that is where we are heading, and where we would continue to head, if we attempted to adopt the circular economy model as our national economic system.

Solow saw resources as being things like fossil fuels, and that’s understandable, given that in the 1970’s the discussions around global warming and the burning of fossil fuels were getting more heated, and alternative visions were being proposed. Solow sought to promote the idea that technology would get us through, and that we would be able to continue economic growth through using more technology. We wouldn’t have to change our institutions, our economic systems; our addiction to growth could carry on unharmed, because the market forces would sort us out. The very causes for the ecological crisis will in some future scenario enable us to confront our current problems. It’s like trying to treat a cut with a knife.

Solow did however know the other possibility: catastrophe. Supporters of the circular economy such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation seem to have lost this nuance, however, taking the idea that we can grow and live without natural resources as an economic doctrine, rather than a conditional statement relying on assumptions about the market and about technology. They show no reflection on what ecology has taught us in the past 50 years: the world most definitely does have limits, and human beings must definitely stick within these limits unless they want to risk the future not only of themselves, but of many other life forms on Earth.

Additionally, the circular economy assumes that the natural cycles of the biosphere can be monetised and valued, and therefore quantifiably brought into the economic system. That’s why the biosphere features on their model of the economy. It is simply impossible to value the water cycle or the flow of nutrients or the processes of photosynthesis. Without these, life would not even exist, they are of innumerable value to all life on Earth. They also cannot be quantified and managed by economists, or the very best ecologists, either.

An ideological agenda of technological saviours

The circular economy seems to be yet another way of promoting a highly technical future, whereby economic doctrine such as prioritising growth above all else, and believing in the magic powers of market forces, are able to be preserved, whilst minor changes in product design and coordination are adopted, and large aspects of life are under technological surveillance and management.

If we think of the environmental debate as having two large narratives, which oppose each other, the circular economy is presented as a solution by one of these sides. The larger story informs us that technological progress will save us from ecosystem collapse and climate change, and that human control and management of the environment will enable ecosystems to restore themselves back to ‘original conditions of balance.’ This is the way that global institutions and many countries are heading. They do not change the ideology or doctrine of their systems, preferring to believe that one day, we will develop a magic technological solution to solve our problems. From then on, humans will be able to control the environment and keep the conditions of life stable for years, even millennia, to come.

Robert Solow believed the same thing – we would just invent our way out of resource depletion, because technology would simply adapt to replace natural resources with something else. The circular economy tells us that we will develop recycling technologies that will become ultra-efficient (much more efficient than nature ever could), that we will somehow be able to separate mixed materials like polyester and cotton in fabrics in order to reuse them, and that we will be able to get over the fact that many materials can only be recycled a limited number of times. For example, paper can only be recycled 7 times before the fibres become too short. What do we do with this paper, once it can no longer be recycled? Put it in the landfill to release methane, a known highly warming greenhouse gas? And where do we find new paper from once all the current paper has been recycled seven times? Believers in this narrative would tell us not to worry – either we will cut out paper use altogether, or we will find a way to recycle paper more than seven times… “you just have to believe, man!”

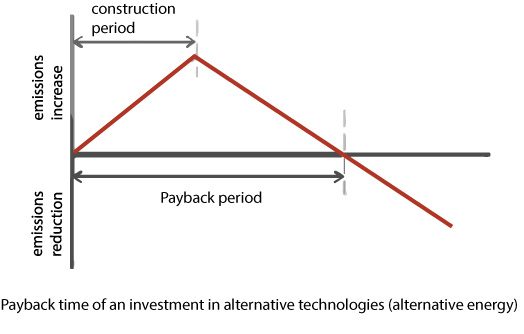

Even if we could find a technological solution, the resources required to put this into place would mean a sustained and notable increase in emissions and resource extraction until this infrastructure is built. Then, it is only after quite some time that we actually see the benefits of such technology. If, of course, it is not too late. The above image explains this.

The other part of this ideological standpoint is to believe that it is possible to control and manage the biosphere. Mario Giampietro’s comments on energy usage have already shown us that human beings are nowhere near capable of managing the water cycle on Earth, given that we only require 11TW per year, versus the 44,000TW needed for the water cycle. Global systems in the biosphere are simply too large and too complex, for human beings to even begin to try to manage.

Likewise, we do not know enough about these systems to pretend that we could decide how to manage them properly. We know that optimisation is not one of nature’s goals, and that natural processes are extremely wasteful. If we adopted circular economy logic of optimisation, efficiency, and zero-waste in ‘regenerating the environment’ we would not be creating something natural; rather we would be acting in ways entirely against the natural laws operating in the environment. If we tried to start adding nutrients into ecosystems which no longer have the same balance of life that they had before, we could simply make everything worse, destroying the new balance of life which has established in these places. We simply do not have enough knowledge about ecosystems to believe that our management and governance will be able to restore the environment to some romanticised previous state of balance and harmony. Read Giampietro’s article here for a more scientific explanation of this.

To sum up this position, here’s the argument in Giampietro’s (very technical) words: “The success of the term circular economy can be seen as an example of socially constructed ignorance in which folk tales are used to depoliticize the sustainability debate and to colonize the future through the endorsement of implausible socio-technical imaginaries.”

Refuting the three principles of the circular economy

- Design out waste and pollution. This is impossible and unnatural. Nature is incredibly wasteful, and human beings will never be zero-waste. We also cannot cut off the inputs of energy, food and nutrients into our economic system. Circularity is not possible within the biosphere. We cannot design a biosphere in which waste doesn’t occur – we are bound to nature’s laws.

- Keep products and materials in use at their highest value. Recycling is great, but consumes large amounts of energy, and portions of the material are lost every time we recycle. We cannot even begin to talk about managing or quantifying products and materials in the biosphere like water, nutrients and energy, which form half of the diagram of the circular economy. These are not maintained by natural systems at optimal conditions, and cannot be valued.

- Regenerate natural systems. To believe that we could regenerate natural systems would be to believe that we understand how these systems work. We simply do not have this knowledge. We cannot think that technological advances will enable us to intervene in natural processes that have been created over billions of years, nor can we expect to create a technological alternative to natural processes in the space of 20-30 years.

For a full academic summary of the critiques of the circular economy, and all the research that is being done into this idea, have a look at the paper by Hervé Corvellec, Alison F. Stowell, and Nils Johansson: Critiques of the circular economy.

To sum up: is the circular economy still valuable?

The circular economy is a great idea for architects, product designers, technological innovators, and those working in the design of goods for consumption. Reduction of waste and lower use of resources is fantastic and a necessary way for human societies to conform the ecological crisis. It is necessary for us to stop extracting more and more natural resources, and begin dealing with the enormous amounts of waste that we produce. Lower emissions are also a great and necessary step towards an ecological future.

The circular economy also draws attention to our current linear economic practices which are leading to ecosystem collapse and creating the wider ecological crisis. Ensuring that companies and individuals are aware of this linear system is an important part of ecological activism. However, companies should be aware that the circular economy is just a fictional model, to help us redesign parts of our productive systems, and not something to be taken as doctrine or a correct representation of reality. It also supports a growth-based vision, which ecologists have said for many years is incompatible with the fight against climate change.

The circular economy is not an economic model. It’s a set of principles for designers to follow. It does not describe reality, rather describes how resources might flow if we were to increase our recycling efforts. Even then, it does a poor job. The propositions of the circular economy, and its assumptions, are not those with which we must work, living on planet Earth. There are certain rules, limits, and an enormous amount of complexity still to be understood about the biosphere, that human beings have absolutely no control over.

Finally, it’s not clear that the circular economy naturally finds an ally in mātauranga Māori either. Life and nature are about balance between two forces, two worlds. Balance and opposition are key concepts in Māori views on the world (look at Georgina Tuari-Stewart’s Māori Philosophy for more on this). Ranginui the sky father, and Papatuānuku the Earth mother, along with the other gods, keep the biosphere alive. Perhaps a better representation of the circularity of an economic model with growth as its founding principle is to be found in the spiral, takurangi, which features on the logo of Āmiomio Aotearoa. Even then, economic growth and hope in technological advances are absolutely not central to the commonly described Māori worldview.

What is clear is that we have to be aware of just what lies behind the big ideas proposed to “solve climate change” and “live better lives.” The circular economy won’t lead us to infinite growth, because infinite growth simply isn’t possible on a finite planet. If we believe in technology and technological advances, we might be willing to take a leap, and place our faith in the market to develop technical solutions, but we risk becoming overly hopeful and ignoring the reality that confronts us.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Global Carbon Inequalities

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 11/01/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology, Politics

share

Carbon emissions are far from equal. Rich people seem to emit more than poor people, and rich countries more than poor ones. Just how bad are global carbon inequalities?

We often hear organisations in New Zealand asking for climate justice. The Fridays for Future movement started by Greta Thunberg and continued in New Zealand by some of our young people is but one example of a climate justice movement. One of the things that we can do to measure climate justice is to by looking at the different emissions of different sectors of the population.

New Zealand’s Government-supported climate action website, GenLess.govt.nz, seems to have misunderstood the whole idea of carbon emissions. In a colourful and celebratory picture, they declare that New Zealand has the fourth highest carbon emissions per capita in the OECD! That actually means, the fourth worst country among all the other rich countries!

To help any wary readers of this Government site out, and for those of you interested in learning more about carbon emissions, here is an explanation of carbon emissions and how they can be compared to show the level of inequality in countries around the world.

How do we calculate carbon emissions per capita (per person)? This is done by measuring the total emissions of a particular country, including all greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide…), and determining the share of these emissions for each person in the country. Because some citizens are wealthier than others, they tend to emit a lot more than people who are less wealthy. This is for many reasons: sometimes these people believe they need to travel a lot and so have large transport emissions; other times they buy expensive and high-polluting items such as private jets; and most have high-consumption lifestyles which require large amounts of resources in order to sustain.

We make these measurements by figuring out the amount of all the greenhouse gases that we produce, and converting these into a carbon dioxide equivalent, CO2e. We have this equivalent because each gas warms the planet differently – methane for example is much stronger than carbon dioxide, meaning it warms the planet faster with the same amount of gas. (See this article from MIT to read more about this). This number is then expressed in tonnes, which is the mass of gases that we are producing over a given time frame.

The inequality aspect of this measure of carbon emissions is a way of determining the difference between those who are more wealthy, and therefore emit a lot, and those who are less wealthy, and therefore emit much less. The greater the inequality, the greater the difference between wealthy and less-wealthy populations.

Carbon Emissions in New Zealand

In New Zealand, things are quite bad. We have a very unequal distribution of carbon emissions. On average each New Zealander emits 15.18 tonnes of CO2e per year. To put that into perspective, if we are to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming, we can each emit 1.1 tonnes of CO2 equivalents per year. To stay within 2 degrees of warming, we can each emit 3.4 tonnes per year. Our annual emissions are therefore, on average, 5 times what they should be if we are to limit the impact of global warming on our planet. Why do we need to limit the warming of the planet? See the article here (coming soon).

In fact, the bottom 50% of income earners, so half of New Zealand’s population, only emit 8.2 tonnes of CO2e per year. However, the wealthiest 10% of New Zealanders emit 45.89 tonnes per year, and the top 1% emit a staggering 139.1 tonnes per year. This top 1% of the population use up the carbon budget of nearly 41 people, each year.

Is there something wrong with carbon inequality?

Imagine that we were on a ship. On this voyage we have enough food to sustain everyone on the ship for the whole trip, plus a little bit more. But, one of these people decides that he’s going to eat much more than his allocated share – enough for 41 people. He starts eating, and day by day the food supply decreases for the whole crew abord the ship.

Is there a problem here? There’s no contract saying that this person can only consume his portion of the food each day. He’s free to eat as much as he wants. But the more he eats, the more other people will starve.

Some people will respond to this by saying that on this ship, it’s a matter of survival of the fittest. This person is acting in his interests to eat as much as he can. After all, he’s allowed to, and if he loves food, then why should we stop him?

Others will respond that in fact this person’s actions are wrong. They are eating more than their fair share of food, and as a result, other people will go hungry in the future. By being on the boat, there is an implicit understanding between the people that they will each share the resources evenly, so that everyone will be nourished and healthy at the end of the voyage.

The problem comes when we ask, what shall we do with this person? Some will say – do nothing! There isn’t a problem, and we can sort out the other (malnourished) people later on. Others will say we should cut off the food supply of this person, because they have already consumed more than their own share for the whole trip. Others will argue for something in the middle.

Carbon emissions inequality is the same. For us to stay within 1.5 degrees of warming, each person is given a budget of 1.1 tonnes of CO2 equivalents per year. To stay within 2 degrees of warming, we can each emit 3.4 tonnes per year. Most of us in developed countries like New Zealand will be over these limits. Certain people however have decided that they are going to emit an enormous amount more than their fair share. Much, much more.

Here we have one way of looking at climate justice. How do we make sure that each person has a similar degree of emissions, and how do we make sure that the ones who are emitting the most are the ones who bear the greatest consequences? Because, as we have seen, and will continue to see, it is always the least wealthy and most precarious people who bear the brunt of the effects of climate change.

What about the rest of the world?

In 2022, the World Inequality Database released the World Inequality Report 2022. This report contains a section on carbon inequality across the world.

On average, each person on planet Earth emits 6.6 tonnes of CO2e per year. That’s less than half the average New Zealander.

The graph from the report below shows us the carbon inequality across the planet. The least wealthy 50% of the world’s population – some 4 billion people – only emit 1.6 tonnes each per year. They’re within the limit for the Earth’s warming to be kept below 2 degrees. The middle 40% are emitting 6.6 tonnes per year. The top 1% however are emitting 110 tonnes of CO2e per year. That’s the same as 68 people in the bottom 50% of the population.

How does this compare throughout the world, when we look at different geographic regions?

The closer the difference between the three bars, blue, green, and red, the more equal a particular region is when we talk about carbon inequality. When there is a massive difference between the bars, these regions are very unequal.

What we see here is that Europe is the most equal among the regions shown here, with the top 10% emitting only 6 times more than the bottom 50%. In most other regions, however, the top 10% emit around 10 times more CO2e than the bottom 50%, with the exception of Sub-Saharan Africa, where the top 10% emit 14 times more. Their top 10% only emit 7.3 tonnes each, however, compared with the top 10% of North Americans who emit 10 times that amount – 73 tonnes per year. Similarly, the poorest North Americans, on average, emit more than the richest people in Sub-Saharan Africa, and almost the same amount as the richest in South and South-East Asia.

Remember that in New Zealand, the top 10% emit 45.89 tonnes of CO2e per year, just over half that of a North American in the same wealth category.

As we can see, the world is quite an unequal place when it comes to carbon emissions. When we think about the individual carbon budgets described above, some people have a lot more effort to put in than others, if we are to meet these goals.

Critiques of emissions policy and carbon calculations

This brings up the question of scale and impact in climate change policy. For example, limiting the flights that are made by private jet, or banning these flights entirely, will impact the carbon emissions of the wealthiest 10% of the population, and have almost no impact on the rest of the population – who, for a large part, have never even been in an aeroplane.

Actions that limit the emissions of the wealthiest of our populations often have a large impact on total emissions. Policies that limit the emissions of the least wealthy people, however, often have very little impact on total emissions. We should keep this in mind when considering carbon emission-related policies.

It’s also important to keep in mind that calculating true carbon emissions and carbon dioxide equivalents is almost impossible. On large scales, we can estimate a lot of things, but many small pieces of the equation are often left out. In order to calculate the emissions relating to the four carrots you bought at the supermarket last week, the quantities emitted are so tiny they often become simply ‘0’ in the overall calculation. This means that the emissions of your consumption are dramatically lower than they would be, had we taken absolutely everything into account (which is very, very complicated and difficult to properly measure).

Another problem with carbon calculations is what we include. Often New Zealanders’ emissions are referred to as being around 6 tonnes per person, per year. This is just carbon dioxide, and doesn’t take into account other greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide. You can see the difference on the Our World in Data page. The website FutureFit.nz uses an average total value of 7.7 tonnes per year, which is based on a calculation done in a research paper in released in 2014, which used data from 2007.

The figure used here, 15.18 tonnes per New Zealander, per year, includes these other greenhouse gases. Therefore, the emissions related to producing dairy and meat for export is included in the average emissions total of each and every New Zealander, because this is a collective emission due to our country’s production choices. Future Fit, for example, don’t use this higher figure, because it would involve emissions that don’t directly relate to your own choices. These collective emissions are almost impossible to reduce or remove without large scale change.

We should also remember that the debate on carbon emissions is only one part of the much larger ecological problem. We’re also acidifying the seas, destroying natural resources, losing biodiversity through more animals becoming extinct, degrading the quality of our water and soil, and more. Air pollution is part of the changes in weather and temperature that we are seeing. However, managing only our carbon emissions is insufficient to deal with the ecological problems that we are facing.

From a more methodological perspective, carbon emissions and carbon accounting can be a good thing, as a statistic. This measurement can bring our attention to inequalities, give us a rough guide of the impact of our production and consumption relative to other countries, and help us to see if we are going in the right direction with the actions we take. The numbers are also a good tool to get people motivated to reduce their score – and if through small changes, people are able to see their carbon emissions decreasing, they’re more likely to continue with these behaviours in the long term.

However, at the core of the directive to measure carbon emissions is the idea that nature and the environment are manageable resources, which can only take a certain amount of greenhouse gases before the balance is lost and life becomes threatened. This isn’t the case – for one, the environment cannot be managed and is not a quantifiable resource. Second, there is no limit beyond which the planet will be out of equilibrium. Nature doesn’t have equilibriums; rather, these are tools that ecologists use to understand the way that nature works. For more on these topics see this article (coming soon).

Looking for more?

Are you interested in knowing where you sit in terms of global wealth and income? The World Inequality Database have a handy calculator which can tell you both where you sit in New Zealand, as well as how you compare to other countries, and the rest of the world.

If you’re looking to get a rough idea of how your choices impact your total carbon emissions, you can calculate your carbon footprint at FutureFit.nz, and see how this relates to others in New Zealand, as well as what areas of your consumption are the biggest contributors to your score.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Political Ecology dictionary

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 10/01/2023

- Ecology, Politics

share

Wondering what all these new words mean in political ecology? You’ve come to the right place! Words are ordered in alphabetical order.

New words are often added, so check back soon if the word you’re looking for isn’t here yet. Or, send us a message to let us know you’d like it to be defined here.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

A

Adaptation: The response to current or expected external stimuli, or to its effects, through adjustments made to a natural or human system, either to decrease the negative effects of the stimulus, or exploit the advantages. Natural systems often adapt in spontaneous and reactive ways. Humans, however, adapt both with intention, will, and prediction, as well as in accidental and unpredictable ways. Humans (and other living beings) can adapt in groups or individually, and can adapt by changing themselves, or using external elements to their advantage (like technology).

Anthropocene: term used to refer to a new geological era, after the holocene, which is marked by the impact of humans on the earth. Exactly when the anthropocene might start is under debate – some say it is with the start of the industrial revolution in the 18th century, others say it’s more recent, around the 1950’s, with the beginnings of the Great Acceleration.

Anthropocentrism: refers to both a perspective on knowledge, and a moral position. As a claim about knowledge, anthropocentrism asserts that humans are at the centre of the world they inhabit: everything is seen through human eyes, rather than from the point of view of animals, rivers, etc. As a moral position, anthropocentrism refers to the idea that only human beings are capable of moral thought and judgement.

Apocalypse: often part of ecological discourse, an apocalypse is the ‘end of the world’. Which world, and just how much is destroyed, changes according to the scenario being put forward. People believe we are heading towards apocalypse often because of the lack of real measures being taken at a global and systemic level to combat the ecological crisis.

B

Biocentrism: a moral position referring to the fact that all living beings are deserving of the same rights and relationships as human beings. The Whanganui river being given the same legal rights as a human person is an example of biocentrism.

Biodiversity: often thought of as another way of saying ‘biological diversity’. This means that there are a large number of different species on the planet, each with unique characteristics developed over many years. In conservation biology, biodiversity is a way of seeing the world – a political and moral position. This position asserts that greater diversity is better for an ecosystem, and for the world, and thus we should combat the extinction of many different species.

Biopower: a term by French philosopher Michel Foucault, used to refer to a type of power which is exercised when humans are thought of as populations, in statistical and controllable ways, rather than as individuals with specific and diverse attributes. The collection of population data, along with the control of bodily procedures, and public health campaigns are all forms of biopower.

Biosphere: refers to the fine geological, physical, chemical and biological envelope on planet Earth that supports all life. The biosphere is also the habitable zone – the place where things can live and thrive.

C

Capital: Ecological economics views capital as a way of discussing the different types of matter which are moving around the economic system. There’s environmental or natural capital, like trees and vegetables and soil; social or human capital, in the form of workers, relationships, etc.; and manufactured capital – the goods that are bought and sold on the market. The current economic system considers all these things as one type of thing, resources with the same qualities, and with the idea that the goal is to accumulate more of these things.

Capitalism: the practice of the indefinite exploitation of resources in order to generate more capital, and therefore have growth in the economy. In the liberal economy, capitalism is a way of organising the production and exchange of goods and services. This is possible because of private property and freedom of exchange in the market, which is supposed to lead to an optimal distribution of resources. The goal of this system is to accumulate more capital, or wealth, often in the form of money or property.

Carbon: carbon is an element with the number 6. It is the fourth most abundant element on the Earth. Often when we read about carbon in the ecological context, people are referring to carbon dioxide, which is a natural byproduct of respiration and a greenhouse gas responsible for the warming of the planet.

Carbon budget: a carbon budget refers to the amount of carbon dioxide equivalents that a particular person, enterprise, or government can emit within a certain time frame. If we are to halt global warming, we need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. This means allocating a certain amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted to different parties.

Carbon footprint: the carbon footprint is an idea created by the petrol industry to push the responsibility from the industry onto the individual consumer. A carbon footprint is the amount of carbon dioxide equivalents a person puts into the atmosphere through their activities in one year. This is measured in tonnes. For us to stay within 1.5 degrees of global warming, each person can only emit 2 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. Currently the average New Zealander emits 15.8 tonnes.

Catastrophe (and catastrophism): When unpredictable environmental events cause already vulnerable societies to break down or collapse, this results in extreme events that we call catastrophes. Catastrophism, or disaster theory, is the idea that we must employ the principle of precaution – to prepare for the impending catastrophe that we may encounter, and therefore mobilise the resources of the society to do so.

Circular Economy: this is the idea of an economy without waste, where all inputs into the economy are used by those who need them, then they re-enter the economy to be transformed into another product, for another use. The circular economy is more than just recycling, but thinking about the ‘life cycle’ of a product, and what happens after the product is no longer used.

Climate: the weather conditions of a particular location, such as wind, rain, temperature, sun exposure, etc. In environmental theory, the climate is something to be concerned about because it is responsible for the conditions of the planet which made life possible, such as fairly stable temperatures, predictable weather patterns, etc.

Climate change: this term refers to the fact that the weather conditions on the planet are changing as a result of human activities. Weather is becoming more unpredictable, and more extreme weather events are occurring, as well as global temperatures increasing, and some places becoming more dry, and others more wet.

Climate skepticism: This is not a scientific theory or a doctrine, rather a position taken up by certain individuals and organisations in order to deny the reality of climate change currently occurring, or to deny that this climate change is a problem worth worrying about. This position was common in the oil industry, where companies would create theories to sow the seeds of doubt among people, to be able to continue extracting fossil fuels and warming the earth. Nowadays, this position is popularised through sites such as Facebook, with groups dedicated to denying the reality we are facing.

Community: a group of people who maintain certain relationships because of where they live, their interests, their identities, or a shared belief. The antonym of community is a city, whereby people have relations based on impersonal connections such as the law, the government, the workplace regulations, etc.

Conservation: the idea that particular parts or species are deserving of protection, and in cases where they are disappearing, deserving of extra help and resources by humans in order to reestablish themselves. The idea that landscapes hold a certain cultural, artistic, or patrimonial value dates back as far as the 1850’s. Today conservation is about protecting the different species of animals and plants in an area, and not doing anything to further destroy areas which are deemed important or fragile.

Cooperation: a political term used to refer to the fact that many countries in the global North, which are the rich countries, are giving financial aid to countries of the South, generally less wealthy countries, in the name of cooperation and development. In general terms cooperation means working together to achieve something, and on a global scale this is happening, but often to achieve things desired by those giving the money in the North, and not to achieve goals decided by the cultures of the South.

D

Degrowth: a term much more widespread in Europe than in the Anglophone world, degrowth refers to the fact that if we are to have an ecological economy, and respond to the ecological crisis, we need to become agnostic towards growth. That means that economic growth is neither good nor bad – it’s unimportant. For some time now, we have shown that increased growth is not a measure of the health, happiness, and wellbeing of a particular nation. Infinite growth also leads to the exploitation of resources, pollution and waste, and the destruction of the planet. The idea is that we should exit this society obsessed with growth for the sake of growth, and choose another objective.

Deep Ecology: a position proposed for the first time by Arne Naess in 1973, deep ecology refers to an intellectual current making use of spirituality, religion, myth and narrative to advocate for the protection of nature and a response to the ecological crisis. Deep ecology is opposed to shallow ecology, which is concerned only with problems of pollution and resources, and not with the relationship humans have towards nature. A position which has been criticised a lot, but is still maintained today.

Deforestation: refers to the change in use of particular areas of land, through the destruction and clearing of what was previously growing on this land, such as plants, trees, etc. and the subsequent loss of habitat for the creatures that previously lived in this area. Deforestation is happening across the world, and perhaps the worst example is in Brazil, where the deforestation of the Amazon will, if it continues, cause massive changes to the Earth’s water systems.

Democracy: a form of political society originating in ancient Greece, a democracy is a society in which the citizens, each equal in rights before the law, have an equal and regular say in public decisions made by the state. Democracy is often an important part of ecological politics, but it is often also criticised. Some say that a more authoritarian approach is needed to confront the crisis, by putting into place drastic measures in short time frames. Others argue that democracy, as the governance of the people by the people for the increasing wellbeing of the people, is not compatible with ecological politics, because we cannot keep increasing our living conditions with finite resources on the planet. Others still argue that democracy is at the foundation of any ecological politics, and we will only see change when people vote in and participate in an ecological politics.

E

Ecocentrism: An alternative to anthropocentric thought, this current was developed in the 1970’s. Initially this approach was the opposite of technocentrism, which viewed the ecological crisis as a technical problem requiring the use of technology to solve it. Ecocentrists saw the larger scale of the problem and refused the reductionist approach of technocentrists. It’s not just about adding technical solutions, but also about modifying our economic system, changing our relationship with nature, and more.

Ecofeminism: A sub-current of ecology and feminism, ecofeminism sees the causes of the ecological crisis and the feminist struggle as being one and the same. Women are often the first to feel the effects, and the most vulnerable in ecological disasters. Likewise, the patriarchal system of governance and the imposition of traditional masculine values such as domination, colonisation, desire for growth no matter what consequence, etc. are root causes of the ecological crisis. Ecofeminism denounces the social and gender categories which consider human beings as all of one nature, such as ‘rational agent’ or ‘white heterosexual male from the West’.

Ecology: the science of the study of the relationships maintained by living beings with their physical and biological environment (other animal and non-animal species). Today, ecology refers to the quantitative and qualitative study of populations of living beings, of their equilibriums, and their variations in the natural conditions of life.

Ecosystem: a collection of plants, animals and other living beings living in a defined area with certain climatic and geological conditions.

Environment: strictly speaking, the environment is what surrounds a particular object, that which is exterior to it, that which is not the object itself. More commonly, however, the environment refers to something similar to ‘nature’ – trees. rivers, animals… the things which are not civilisation, not society, non-human.

Emissions: each time a fossil fuel is burned, like coal, oil or gas, this liquid is converted into a gas which enters the atmosphere. These gases, the product of burning fossil fuels, are called emissions. Emissions could also refer to all by-products of a particular activity that enter the environment.

Eurocentrism: the point of view which puts a white, Western viewpoint as the main perspective through which something should be considered, ignorant or unwilling to recognise other perspective such as indigenous knowledge.

Evolution: the idea that natural history progresses because of two things: the possibility of genetic modifications between different generations, and because of natural selection. That means that life forms change and develop because of random changes to the makeup of creatures, which makes them either better or worse at living in their environment. Charles Darwin (1809-82) is the common reference for evolutionary theory.

Exaptation: the idea in evolutionary biology that a trait might change its function during the evolutionary process. For example, bird feathers helped to keep birds warm, then might have later developed the function of flight. An alternative way at looking at adaptation, because traits do not appear to serve particular functions, rather they appear and then later become useful for certain functions. The exception precedes the norm – exaptation precedes adaptation.

F

Finance (carbon): the approach of solving the ecological crisis through manipulations made to the economic market by incentives and schemes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This often takes the form of carbon credits, or quotas, which can be bought and sold. People can also compensate their cardon dioxide emissions by activities such as planting trees or purchasing other’s unused credits. This approach reduces the ecological crisis to a matter of accounting, and ignores the social and environmental aspects.

G

Gaia (hypothesis): Lynn Margulis and James Lovelock developed the Gaia hypothesis in the 1970’s. This hypothesis postulates that the troposphere, the part of the atmosphere where we find life on earth, is a complete and self-regulated system. Conditions such as temperature, chemical composition, oxygen, acidity, etc. are controlled directly by the living beings of the planet. The planet is able to keep the conditions for life at an optimal and stable level through certain planetary mechanisms. This is just a hypothesis, and the idea that the whole Earth is capable of regulating itself in one big system is hotly debated.

Geo-engineering: the idea that new technologies will and should be developed in order to control the environmental and climatic conditions such that life on earth can continue despite the ecological crisis. This view originated in military circles, desiring the complete control and domination over a particular environment, and looking for ways that humans could live in the most uninhabitable places. Such technologies that intentionally modify the atmosphere, and carbon-capture technologies, are part of geo-engineering projects. This projects often lead to enormous unintended consequences, which are not considered by those launching the project.

Globalisation: there are two types of globalisation – the increase in the possibilities for movement and exchange across the planet, and secondly the exportation of certain cultural norms and economic and political doctrines from countries such as the United States. The first is a good globalisation, the second is often not so appreciated. Globalisation also refers to the fact that, since we began seeing ourselves as all on one planet, we have changed our regard towards the world from a local perspective to a global one. Now it’s possible to think of all creatures on Earth, all humans on Earth, rather than just those which are in our immediate environments.

Greenwashing: the act of making it seem like someone or something is acting in ways that support the resolution of the ecological crisis, when actually they are having the opposite effect. Companies and governments are the biggest greenwashers, and we need to be vigilant to question their claims of ‘doing good’.

Growth: Most commonly thought of in biological or economic terms, this idea is inscribed in all cultures influenced by the West’s modernity. To grow is to develop, to advance, to progress, to go further… all things which are seen as good and beneficial things in Western culture. Growth is inherently tied with ideas of ‘more’ and ‘better.’ Growth in biology simply means to increase in a particular measure, such as size. A plant grows, and this is neither good nor bad.

H

Habitat: the territory used for the reproduction of a species, its eventual acclimatisation, and its development. The place of dwelling. This includes all the conditions which are necessary for the development of this particular species, including food sources, temperature, other plants and animals, materials used for construction, etc.

Homo faber: the development and use of the atomic bomb indicated a change in the power and scale of humans and their technological capacities. Instead of referring to ourselves as homo-sapiens (rational humans) an alternative proposition is homo-faber – humans who make things. Our intelligence is manifest because we transform our world, we seek to master it, understand and control it.

I

Individual: modernity installed in our societies a unit with an almost sacred value: the individual. Individuality, and individual expression, was deemed to be the highest possible form of society, where each human had freedom and was equally considered in the eyes of the law. This atomistic way of viewing people is not necessarily how they are in reality: humans are also social creatures, forming their identities through interactions and relationships, living in communities, and participating in larger projects than just those that benefit themselves.

Inequality: the fact that there exists a difference between two things, often people, in terms of a particular measurement. Inequalities often refer to the fact that certain people are treated differently to others, have more resources than others, have greater chances in life than others, etc. Free-market economists will say that inequality is not a bad thing; others will argue that inequality is inherently bad.

Investment (socially responsible): Responsible investing is an alternative route to the practices which led to the financial crisis of 2008. Recognising that investments have real-world implications, responsible investing means realising the social, environmental and governmental impacts of making a certain investment. Petrol companies for example would be evaluated not only on their oil reserves, but also their damage to the environment, their emissions of carbon dioxide, and the way they treat their employees and the people in countries where they are extracting oil.

J

Justice (climate): the field of research into how the costs, damages, and benefits of action taken on climate change will be felt and managed by people in different countries, economic groups, and localities. One group of climate justice thinkers advocate that those who have polluted the most should ‘pay’ the most, for example, the United States and other wealthy nations, resulting in these countries paying for the damage caused by climate change in other countries. Other thinkers argue that countries should be left to deal with the consequences of climate change by themselves. Others promote the idea that the atmosphere is a common space, no one country can pretend that they are doing ‘enough’ unless all countries are also pulling their weight.

Justice (environmental): this term appeared in the United States in the 1980s to refer to the actions taken by activists to redress what they believed were climate injustices, such as blocking streets, occupying land, etc. The first to feel the impacts of environmental mismanagement are often less wealthy and marginalised groups, who live and work in conditions with high pollution, and are employed to use pesticides and other toxic chemicals. These are also the groups who have the lowest greenhouse gas emissions per person, and the often the least impact on the environment in terms of pollution. Environmental justice aims to point out that those who perpetuate the destruction of environments should be the ones to face the worst of the consequences; or, at least, those who are not responsible should not be bearing the greatest burden.

K

Kaitiakitanga: the relationship based on an ethic of care and kinship bonds between human beings and their environment according to Māori. Often wrongly translated as ‘guardianship’; more correctly referred to as ‘stewardship’, keeping in mind that reciprocity is at the heart of this idea.

L

Limits: the idea of limits first became popular in the 1970’s with the release of the Limits to Growth report by the Club of Rome. At the time, common ideas of progress and growth were infinite – limitless. In fact, the planet has a finite number of natural resources; there is only so much fresh water, for example, or copper, or lithium for batteries. The idea of limits is central to ecological thinking, because we must recognise that nature and the Earth is not infinite, and all-giving, but a place with certain limits and restrictions. We cannot, for example, continue to pollute carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as we are now, unless we want to become extinct. We must therefore limit our emissions, just as we must limit our consumption.

M

Management (environmental): the belief that the natural systems of the earth require the governance and decision making powers of human beings in order to function in their optimal way. Environmental management presupposed that humans can determine an optimal state for a particular ecosystem or piece of land, and then that they can achieve and maintain this state without other negative effects being had either in this system or in neighbouring systems. In 1995 a study by Holling analysed attempts to manage environments on small scales and concluded that “environmental management leads to less resilient ecosystems […] and sets the conditions for collapse.”

Market: for economists, the market is an abstract idea of the circulation of goods, services, and money. In this system, decisions are decentralised amongst the actors in the system, and because these decisions are supposedly in opposition, price becomes the means by which the market functions. In a more socio-economic sense, the market is the collection of institutions which, through their functioning, come to provide a regulated ‘space’ in which transactions can take place. An example of this would be the fruit and vegetable market, where growers and distributors can sell their food.

Modes of life, ways of living: When we speak of natural destruction, we also often speak of the erosion of ways of life too. These modes are archetypical ways in which people have lived and related in the past. Due to globalised capitalism, industrialisation, technological advances, and more, these ‘ancient’ modes of living are no longer possible to live, even if one chose to. Likewise, modes of life also refers to the ‘consumption society’ – you can choose to live a certain archetypical life, by buying certain goods and choosing to behave in certain ways. Life, and its ways, have become commodified.

Money: simply, money is a means of exchange between two parties to ensure a transaction of equal value. Money gains its legitimacy through social and political institutions and conventions, which are adhered to by the citizens in the society. There need not only be one form of money in a successful society – in the Egypt of Pharaohs, multiple monies circulated and this scheme lasted a long time. Ecological monetary theory looks into the links between the current lending and debt-creation system, and environmental destruction. Loans promote and encourage the growth-addiction that our economy suffers from, and this addiction to growth in the long term leads to environmental destruction.

N

Nature: a hotly debated word in political ecology. Some say that nature does not exist, because nature is only defined in terms of what is not-human, what is outside society, outside the human boundary. Because human beings are a part of this ‘nature’, part of the natural systems on Earth, there is no such difference between ‘nature’ and ‘society’ or ‘culture’. It’s all one. On the other hand, Western societies (and others) have for many millennia reinforced a difference between humankind, and that which is not human, in the form of plants, animals, forests, clouds, wind, etc.

Neoliberalism: Neoliberalism is a political ideology that gained in popularity after the 1929 economic crisis in Europe. Neoliberalism rejects collectivism and the recourse to the dogma of the invisible hand, letting the market regulate itself. In the 1980’s, this became a political programme and economic model with the Thatcher and Reagan governments in the U.K. and the U.S. Now, neoliberalism takes many forms: the globalisation of exchanges, global financial systems, flexibility in the labour market, commodification of the environment and natural resources, structural development plans in less-developed countries, and more.

NIMBY: an acronym meaning ‘Not In My Back Yard.” Used to refer to an attitude towards development often held by ecologists and non-ecologists alike. These people oppose the development of environmental dangers such as large waste sites, nuclear power plants, incinerators, transport infrastructures like roads, but also social infrastructure like social housing, refugee centres, etc., which are proposed to take place in close proximity to them.

O

Overshoot: this concept first appeared in 1980 by William Catton. He advocated for an entirely new approach to sociology and thus a new ecological paradigm. He explains how occidental societies support their lifestyles through excessive consumption and environmental destruction. Instead of looking at the human effects on nature, Catton looked at the environment’s effects on society; namely, that there were only a certain number of resources that we could use before our ideas of development and growth, and the possibility for deluxe lifestyles, would fall to pieces. The term is now popularised by the Earth Overshoot Days, the point at which each country has used up its annual allocation of resources, sometimes only a few months into the year.

P

Permaculture: a contraction of the words permanent and agriculture, permaculture is a form of land use which diverse forms of agriculture are used in order to create lasting and resilient production systems, where the ecosystems and farmland are maintained in their quality, or even enhanced in the long term, by the diverse strategies used. This is in order to avoid the waste and environmental destruction caused by industrial agriculture, such as loss of soil quality. plants and pests developing resistance, etc.

Petrol: for at least a century, petrol has been the most precious material to all of industrialised humanity. Without petrol, it’s unlikely that our standards of life would have improved significantly since the 18th century. However, because petrol is a resource provided by the earth in limited quantities, we will soon run out, and the grandeur of modern lifestyles will begin to decline. The burning of petrol emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which is the principal cause of global warming and climate change.

Political ecology: this term has a different meaning depending on the linguistic tradition. In English, political ecology refers to the empirical and interdisciplinary science which explains the different degradations of the environment by political and economic factors at different scales. In the French tradition, however, écologie politique refers to a movement: no-one will get together to support scientific information, so we must politicise ecology, and take back control of our destiny as human beings. Ecology becomes a political force.

Pollution: an unwanted product of a particular process, which enters an environment with negative consequences for the species living in that environment. Carbon dioxide pollution causes global warming; nitrous oxide pollution causes human health problems, pollution in the form of waste being dumped in rivers kills off fish and plants in the river ecosystems, etc.

Population: a group of individuals that we put together because we believe that they have certain attributes in common, and they function together as a whole from an ecological, genetic or evolutive perspective. The viewpoint of population allows greater understanding of a particular species, but also promotes the idea that such a grouping of individuals can be controlled and managed according to certain criteria.

Principle of precaution: In the face of a potential future major disaster, it is necessary to put in place certain preventative measures in order to limit or stop the damage caused by this disaster. According to this principle, groups, companies, governments, individuals, have the duty to prevent potential major damage if they know a disaster such as climate change is coming. This principle is used by philosophers and ethicists, but also by the justice system and in law, to argue for the protection of people or places.

Progress: a grand idea forming much of the motivation for development in modernity, progress is the idea that things develop and grow along a linear line in time, and that each successive development is inherently better than the previous ones. This concept has religious foundations, coming from the idea of a positive infinity, the linear progression of time, and the destruction of the cosmic world for the scientific world after Galileo Galilei. The victory of abundance has reached its end; abundance no longer exists and the very idea of progress is brought into question in ecological politics. Just where are we going, how, and why?

Property: a three-way relationship between a thing, a person, and a group of others who agree to a particular relationship between this thing and this person. The state accepts to protect the right to ownership over particular things by individuals, companies, and other legal entities. This is what underpins the growth of capital – if I own something, you cannot use it, and must pay me for it. Property also underpins the legal system – I can bring a justice claim before the courts because I have a right to something which is exclusive, and when you breach that exclusivity, the courts see fit to punish you. Te ao tawhito, the ancient Māori world, did not function in terms of individual property, but rather in terms of collective property. Items did not belong to people; rather people belonged to nature, and items were given to them by nature to look after and use.

Prosperity: another big idea from economics linking growth to better living standards, prosperity is the idea that more is better. Ecological economist Tim Jackson is one of the world’s leading thinkers on prosperity without growth, and how we can create a new vision of a thriving human community which doesn’t depend upon economic growth and the ensuing environmental destruction.

Q

Queer: A concept often used in gender studies, but which has implications in ecology too. Queer refers to the blurring of boundaries between what has previously been defined as dualistic oppositions. Male/female is but one example. When we look at what ecology tells us about our place in nature, we see that in fact we are all interrelated, that both ecology and queer theory demand intimacy with other beings, and that ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ are not clear places but rather perspectives that require a certain violence to uphold. For more on this connection, see Timothy Morton’s “Queer Ecology,” and the journal “Undercurrents.”

R

Racism: the belief that humans can be divided into specific entities called ‘races’, accompanied with the belief that some of these races are superior in nature to others. Racism is also the practice of discrimination based on the division of people by race. Anti-racism is ecological because the same mechanisms that supported a racially divided world, like colonisation and economic globalisation, and values of domination and control, are the same causes of the ecological crisis. Malcolm Ferdinand is one contemporary thinker pointing out the links between racism and ecology.