Stories of ecological transition: Ebène l’Adelphe

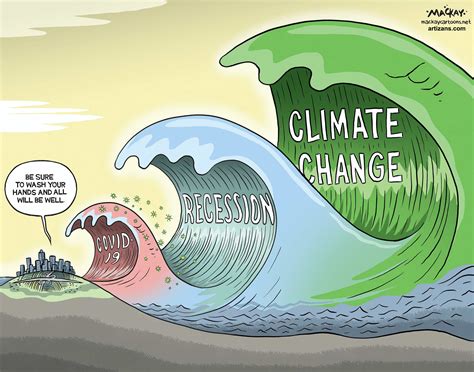

1st lesson : when adults tell me everything is fine, I should probably worry

2nd Lesson: just "ecology" is white dude ecology

Well, about transportation, I am now in a dead end : I did my research about alternatives to the plane but it was not very successful. If you know reasonable options, please, let me know ! Reasonable means for my family : a travel mean over the summer vacations (1 month) and within 6000€ (ticket plane back and forth).

There you go. I had become a feminist and a radical socialist and ecologist. Those 3 fights were all important to me, and despite my belief that ecology embraced them all, I did not see the expected convergence in ecologist groups. Moreover, when I asked my activist peers what was ecology for them, many didn’t quite know, there was no consensus. I was quite disappointed about those people (I am not gonna lie, there were mostly white rich cis dudes) fighting for something they could not quite define. For me, ecology was about links between living beings, so if inter-human solidarity was dead, how could we claim to take care of our connection with the rest of the living?

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

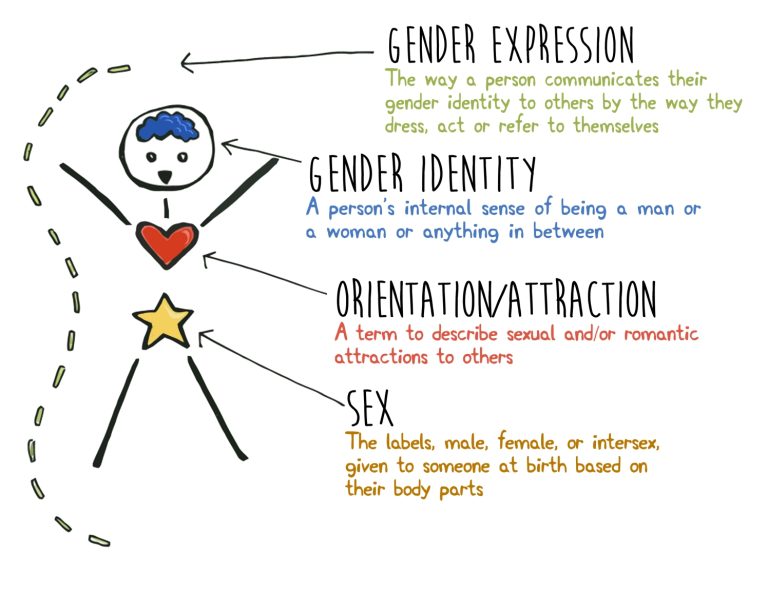

3rd Lesson: Intersectional queer ecology, alias ecofeminism

Bibliography

(1) Lefebvre, Olivier, Letter to Doubting Engineers, l’échappée, 2023.

(2) Preciado, b. Paul, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics, Points Feministe, Paris, 2021.

(3) Wittig, Monique, The Straight Mind, Boston, Beacon Press, 1992.

(4) Lovelock, James, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, Oxford University Press, 2000.

(5) Singer, Peter, Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals (1975), Melbourne, Ecco Press, 2001.

Ricard, Matthieu, Advocacy for Animals, Allary edition, Paris, 2014.

(6) Ferdinand, Malcom, Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World, Polity, Paris, 2022.

(7) Hoskin, R.A. Femmephobia: The Role of Anti-Femininity and Gender Policing in LGBTQ+ People’s Experiences of Discrimination. Sex Roles 81, 686–703, 2019.

(8) Herstory: oncept created/diffused first by the feminist journalist Morgan Robin

(9) Burgart Goutal, Jeanne, Being Ecofeminist – Theories and Practices, L’échappée, collection versus, 2020.

(10) Haraway, Donna, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

(11) Preciado, b. Paul, Dysphoria Mundi, Grasset, Paris, 2023.

(12) La Poudre with Lauren Bastide Episode 126: Myriam Bahaffou

Conversations écoféministes, Karina Kochan, Léa Chancelier, Jasmine Marty, Capucine

Néotravail #20: Des Paillettes sur le Compost de Myriam Bahaffou – Les coups de ❤️ d’Hélène & Laetiti

Avis de Tempête S2 E5 – Pratiquer les éco-féminismes depuis les marges

Book : Bahaffou, Myriam, Des paillettes sur le compost : Ecoféminismes au quotidien [Glitter on the Compost: Everyday Ecofeminisms], Le passager clandestin, 2022.

(13) Hooks, Bell, Feminist theory : from margin to center, Cambridge, MA : South End Press, 1952.

(14) Website of the association https://www.labodesresistances.fr/

(15) Bayeck, R. Y, Positionality: The Interplay of Space, Context and Identity. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2022.

(16) Sartre and the Existentialism, Camus and The Rebel… yes, yes, I know their are cis-white-het men, but don’t you think I need to add a bit of traditional Frenchness to this article to make it readable ?

(17) Hache, Emilie, RECLAIM, Anthologie de textes écoféministes, Editions Cambourakis, 2016

(18) Neimanis, AstridA, Hydrofeminism : becoming a water body, https://philo.esaaix.fr/content/hydrofeminisme/hydrofeminisme.pdf

Our Stories of Ecological Transition series puts a spotlight on inspirational people who have changed not only who they are, but how they treat the world. They've done this with courage and strength, and their stories help us all to see the ways we could change, too.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024

The rich and climate change: their real impact

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 12/02/2024

- No Comments

- Politics

share

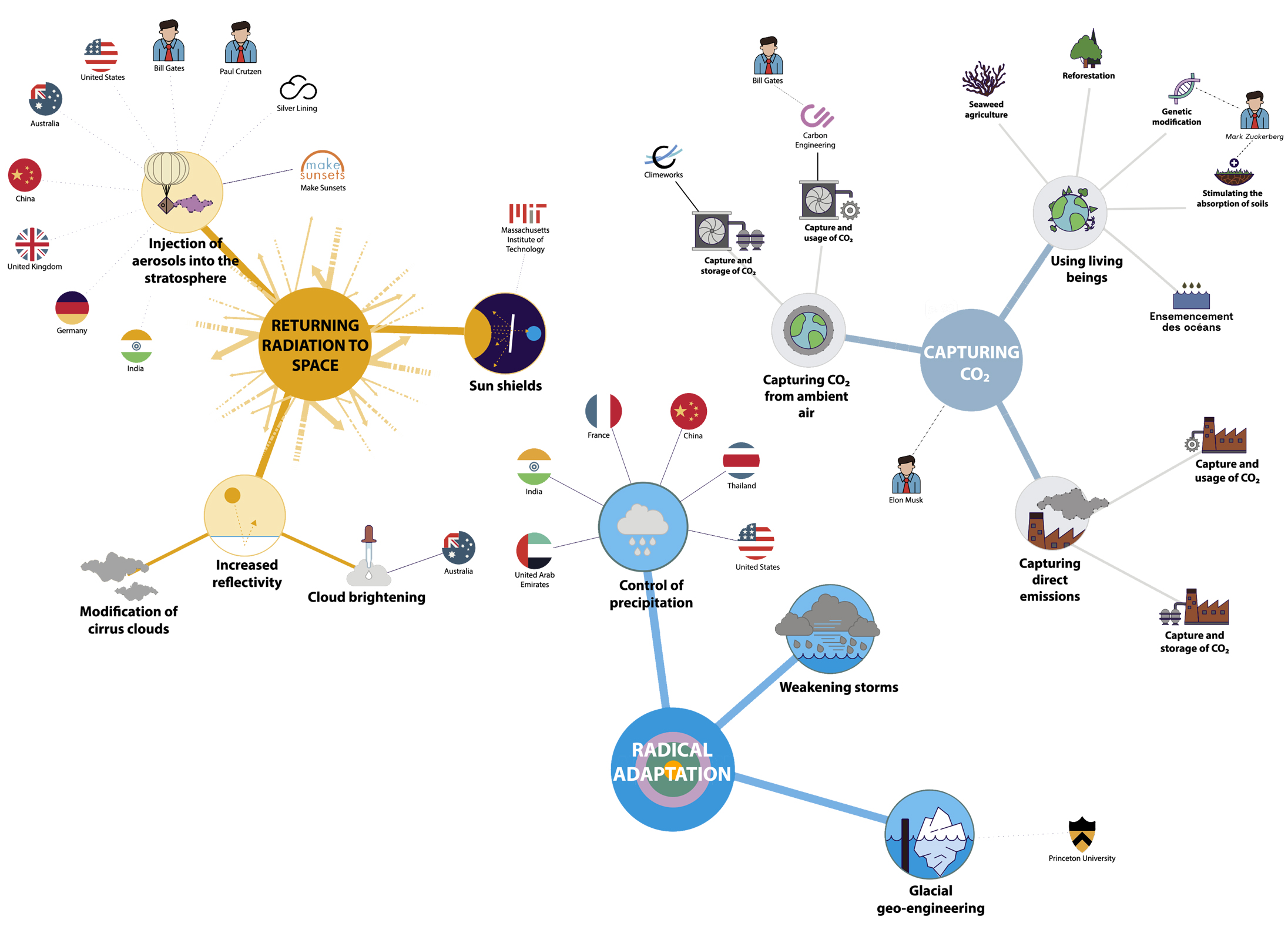

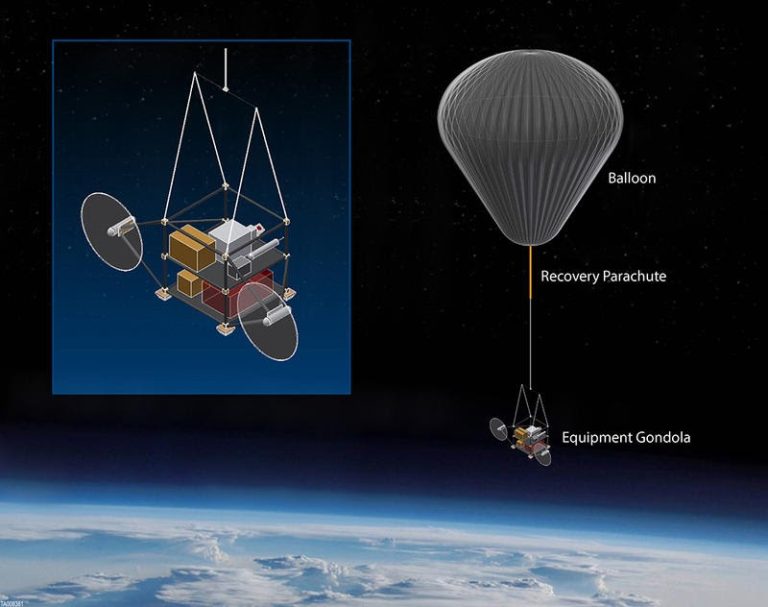

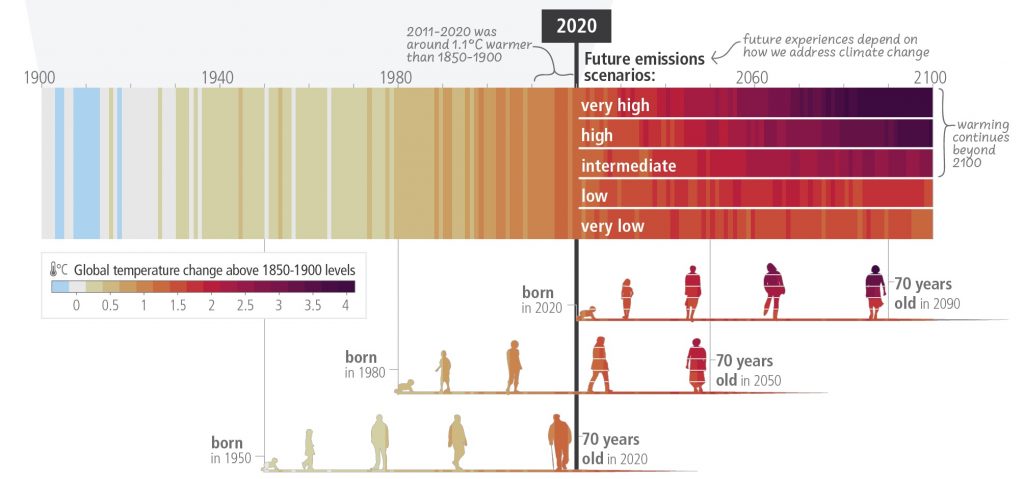

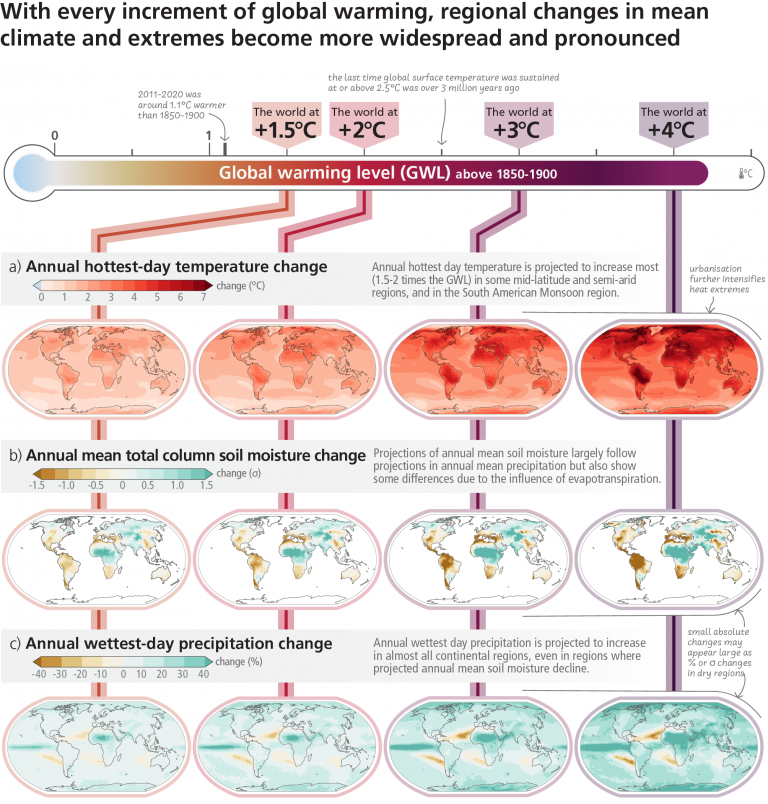

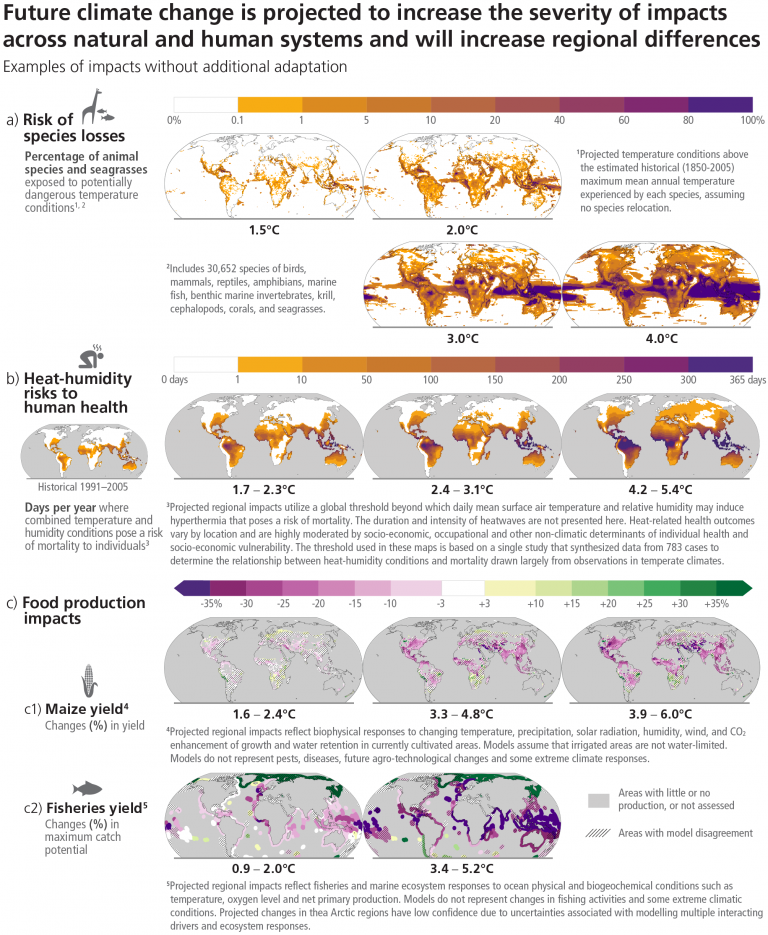

Much of the international debate on sustainability focuses on individual behaviours. This criticism is the same, whether you are a farmer from Canterbury or Jeff Bezos in the United States. However, the influence of the mega-rich and their entourage, through their investments and their control of the framing of the climate debate, is much more important than how many flights they take in their private jets.

Image: Billionaires Bill Gates, Richard Branson, and Mike Bloomberg, with other wealthy individuals who fund climate projects. Francois Mori/AP.

In an interview with Sophia Money-Coutts on Tatler in 2018, Johan Eliasch said something which reveals the attitude of many rich people towards climate change. She reports him saying in their interview:

‘I can do anything I want because I’ve got my rainforest,’ he says, smiling. ‘I’m probably the most carbon-negative individual in the world.’

Eliasch is part of a special class of people: the global elite of the mega-rich. He is worth an estimated 3.6 billion GBP, or $7.5 billion NZD. As well as being Chairman of the sportswear company HEAD, Eliasch has held various positions in the British Conservative Party relating to the environment, and runs an organisation called Cool Earth dedicated to protecting the tropical rainforest. He bought 1,600 km2 of Amazonian rainforest in 2005, and closed down all logging operations on the land, which he is now ‘protecting’ for the good of everyone.

In 2008, he wrote a report for HM’s Government in the UK about the possible benefits of using financial mechanisms to preserve forests and prevent deforestation. This report then went on to become influential in guiding policy decisions for the development of REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation), a global initiative which is part of the International Climate Change Convention. This initiative means that he can earn money on the land in Brazil that he is protecting from deforestation.

The same story is told countless times over, for countless other mega-rich people, in the study by Edouard Morena, Fin du monde et petits fours: Les ultra-riches face à la crise climatique (End of the world and petit fours: the mega-rich face the climate crisis). According to an Oxfam report, in 2019, the richest 1% of people worldwide were responsible for 16% of global carbon emissions: the same as the emissions of the poorest 66% of humanity (5 billion people). Despite their obvious personal implications in causing this crisis, these wealthy individuals saw an opportunity to increase their power, their fortune, and their wealth. They decided to take action on the back of the crisis.

Morena shows in his book how these wealthy individuals are intentionally directing the climate debate towards a certain version of ‘green capitalism.’ This system ultimately benefits businesses and the wealthy, at the expense of the poor and the environment which the system is supposed to be protecting.

We will explore how the mega-rich, along with a group of relatively well-off academic and professional elites prevent the advent of a just and adequate ecological transition. You, the reader, could be part of a bright and connected future that is both ecologically sober and greatly fulfilling, and create this future in a way which doesn’t increase the wealth and power of a small number of people at the expense of everyone else. If there’s one thing that you take away from this article, it is that there is another way.

The Climate Glitterati and their interests

Kevin Anderson, a British climatologist, calls some of these wealthy elites the “climate glitterati.” Who are they, and what are they doing?

Each year, the World Economic Forum is held in Davos, Switzerland, where countless members of the climate glitterati come together to discuss what must be done to save the world. Thought leaders, prime ministers, wealthy billionaires, and more, are in attendance. They sit in opulence and talk about key issues such as climate change and inequality. In 2020, Morena reports, Al Gore and Jane Goodall talk about the climate crisis. Goodall blames overpopulation for the problems we have now, saying that “we wouldn’t have these problems if the population was the same as it was 500 years ago.” She repeats the same neo-Malthusian arguments that many wealthy people use to shift the responsibility of climate change onto the shoulders of someone else. It’s not us that are the problem: it’s them. Morena quips that they will be “invited again” to Davos, because they have managed to softly reassure the champagne drinkers that their actions are completely rational and safe.

These wealthy individuals and powerful people seek one thing, according to Morena: to save themselves. The champagne and small bites of food on platters continue to be served whilst discussions about the future of humanity unfold. The contrast could not be greater, yet these people seek comfort and reassurance in the face of the crisis.

They go about it in two different ways:

- One group prefers to distance themselves from everyone else, and live in a secure bubble on their own estate. They’ve bought land in New Zealand or Patagonia, where they can travel by private jet if everything turns to chaos. They can be called the survivalists.

- The other group are what we referred to before as the “climate glitterati.” They want to save themselves too, but instead of hunkering down, they prefer to travel the world telling other people how to solve the problem. They’ve realised that they have more to gain (or perhaps less to lose) by directing the global climate debate and ensuring that their interests are protected.

“Their climate emergency is not the same as our climate emergency”

Everyone is exposed to the risks of climate change. The fact is, however, we are not facing the same outcomes. The wealthy fear that their golf courses, enormous mansions by the sea, and their investments in fossil fuels will be hit by the effects of climate change. The value of their portfolios might decline, which makes them, like everyone else, anxious and fearful. They might lose power, status, or credibility. The more fiscally sober among us might fear increased prices, an unpredictable storm that wipes out an apple orchard, or an unbearably warm summer which results in the deaths of countless elderly. This is most certainly not what the ultra-wealthy are worried about.

Instead of owning up to their responsibility for the climate crisis, these billionaires want to paint themselves as heroes. We are supposed to see them as the only people who have the wealth, the ideas, the power, and the guts to save humanity from this mess (the mess that they bear a greater responsibility for, remember). They are the new shining lights of our society, and we should desire to be like them.

Just like Johan Eliasch, Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon and one of the richest people on the planet, has begun to paint himself as a climate hero and invest in climate-related organisations and schemes. After an emissions-intensive trip into space a few years ago, Bezos is said to have realised the fragility of life on Earth. Following this, he set up the Bezos Earth Fund, worth 10 billion USD, and another Amazon Climate Fund worth 2 billion USD. With this money, he has begun investing in organisations and companies which support his vision for the future. He’s also been speaking at conferences about the climate and the need to act (with technology and market-based solutions, as we will see).

Bezos is doing this to save himself and protect his assets. In order to justify being at the head of a company with an immense emissions report, and a track record of injustice and human rights issues, he must donate some of his money to support the climate effort. In doing so, he turns the attention away from the inequality that his company is responsible for, and towards the bright, shiny, technological future he is creating (for us).

As Morena writes, “It’s an indirect way of promoting yourself, legitimising yourself and putting the figure of the innovative entrepreneur at the heart of the climate debate and society in general.”

He donates so that he can continue polluting. He donates so that he can take flights around the world, and continue a high-emissions lifestyle. He donates to justify the fact that his company is responsible for huge emissions. He donates to protect his investments and his assets. He donates so that we ignore his anti-climatic actions.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Their goal: more markets, more capitalism, more technology

In a nice house in London, George Polk hosts dinner parties to educate the rich and the leaders of Western society on how to solve key social and economic problems. He’s the founder of The Catalyst Group, “a London-based organisation which works to educate international business leaders on major issues of public policy.”

Morena reports that people come to these dinners to learn about climate change, and in turn, be informed on the ways in which public policy should act to solve it. Of course, Polk is out to educate them about the possibility that business and investments can be protected through a beautiful thing called “green capitalism.” It’s possible to have your cake and eat it too.

The key aspects of Polk’s strategy to fight climate change are the same as the ideas put forward by the consulting company McKinsey, Al Gore, and a host of other elites seeking to manipulate the climate debate in a certain direction. There are two pillars to their approach towards green capitalism:

- The marketisation of nature,

- The reliance on technology and innovation

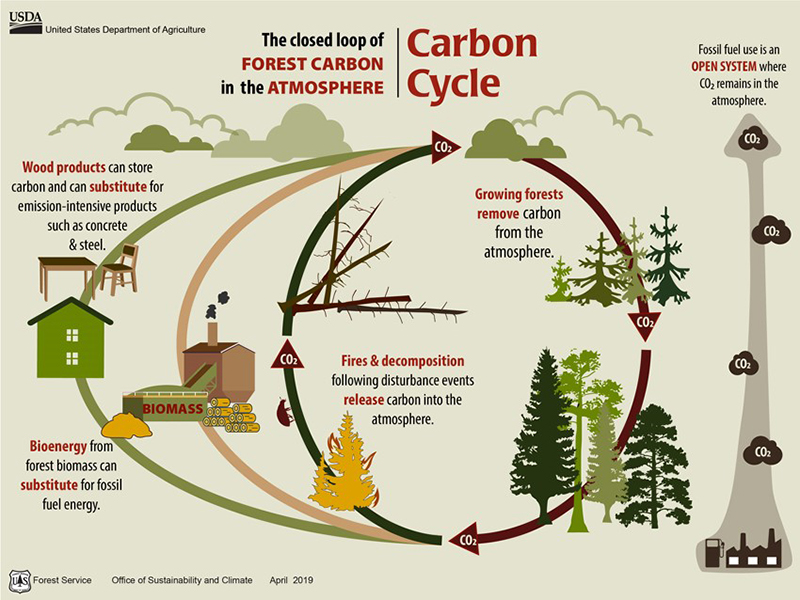

The first of these, the marketisation of nature, is referring to several schemes set up to pay people who own land and who don’t cut down the trees on that land (or who plant more trees). The idea is that wealthy people and businesses can continue to pollute, because somewhere there are trees that are sucking up all this pollution and storing it in the ground. The person who owns those trees is providing a service to the rest of society, so should be paid for that service.

This marketisation of nature takes many forms in global agreements, being referred to as a carbon credits scheme, an emissions trading scheme, the global programme REDD… This scheme benefits landowners, who extract massive profits from these schemes from companies who have no intention of changing their business plan in order to reduce their ecological impact. What’s more, in places such as Brazil, locals are being forced off land that they have occupied for generations, because this land is now owned by wealthy billionaires or companies engaged in carbon credit trading. Consequently, they are no longer able to use this land for sustenance: most of the time in ways that are sustainable and respectful to the forests themselves. Others, who are employed in the logging industry, are similarly losing their jobs, which previously was one of the only ways to make money in some of these regions. You can read the Guardian article about these communities being forced off their lands here. A similar study based in Asia on Mongabay about the communities who are responsible for taking care of forests is available here.

The Guardian also studied the effectiveness of these projects at stopping deforestation, and the real impact that they have on offsetting carbon emissions. The title of the main article says it all: “More than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows.” That’s almost ALL of their projects that have almost no ecological impact, yet they are behind an industry worth more than $3 billion NZD. The Guardian undertook nine months of research into these schemes to uncover several cases of human rights abuse, very little action to stop deforestation, and gross overestimates of the amount of carbon being stored. This article in Science concludes that “most REDD projects are less beneficial than is often claimed.”

The marketisation of nature is completed by the economic viewpoint that nature is something that renders services to human beings, each of which can be calculated and valued in monetary terms. The value of a particular forest might be $200,000; the value of a small lithium mine $2 million, and so on. Economists are therefore able to make calculations according to this about whether it is worthwhile destroying the natural environment, because now we know what it is ‘worth’. These calculations take no account of the real ecological impact of disturbing the land, and forget the fact that once we have sawed the branch we are sitting on (completely disturbed the biosphere), no amount of money will be able to get these environmental conditions back.

By valuing nature like this, economists believe that we can then act to protect the most ‘valuable’ parts of the natural environment. This will be society’s conservation project, to protect and restore ecosystems. To complement this, we need to do something about the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions which are causing global warming. For this, we need technology, the elites will say, and for that technology, we need money in the form of investments.

Investments and partnerships are another financial tool used by the elite to facilitate business despite the ecological crisis. You might have heard of green investments, or investing in green-tech or clean-tech, referring to low-carbon technological projects. These private investments are often guaranteed by the state through various banking mechanisms that mean that the state will bail out investors if their investments don’t end up creating value. Morena writes, “Their aim was in particular to transfer the risks associated with their investments in the low-carbon transition to the states – and therefore to society as a whole – and thus to participate in the advent of a “derisory green state”, to use the terminology developed by the economist Daniela Gabor.” These investors campaign for ‘green finance’ including tax credits, guaranteed loans, and public-private partnerships, to shift the risk for their investments in the future they want to create over to the society, rather than bearing this risk themselves.

The figure of the entrepreneur is a key promotional tool in order to communicate about the technological future these elites envision. Morena writes, “by emphasising freedom, innovation and the individual as vectors of social and environmental progress, this discourse contributes a little more to positioning the figure of the innovative entrepreneur, both careerist and heroic, at the heart of our social and economic imagination. [… This is part of] a broader effort to construct and present enlightened and enterprising economic elites as climate savers and leaders of the low-carbon transition.”

Those who know how to run a business, how to build a brand, how to make good investment decisions, and how to seize the opportunities of the market are, according to this story, those who are most capable of ‘saving’ societies from the risks of climate collapse. I fail to see the connection here. Understanding the functioning of ecosystems, mechanisms of life on Earth, and the ways in which humans extract and produce resources seem to me to be the most important qualities for someone who might be able to propose a solution for a collective. However, those exact skills which have led to the development of extractive and dominating business practices seem very unlikely to be the skillset to also present the solution.

Their promise hits at the heart of what many people today in the West consider as freedom, and therefore as something they are unwilling to give up: the freedom to choose what to buy, what we want to consume. To be free, for many, is an economic freedom, rather than an inner freedom or a freedom from punishment for example. We can continue to be free individuals under this scheme, because the basics of capitalist production will remain the same. The goal of becoming a wealthy and powerful individual remains, and the figure of the ‘greened’ entrepreneur, rags to riches story can remain in place. The mega-rich and their supporters are content, because we don’t have to change the story we tell ourselves about success – all we need are a series of market mechanisms and more science and technology to respond to the ecological crisis.

The method: Curves and Communications

The ultra-rich, in the beginning, were not part of international climate debate. However, through a series of coordinated actions, they have become central players through their ideas about the future, in the frameworks established at climate conventions across the planet.

Morena writes, “This state of affairs is the product of an epistemic community of researchers, experts, government representatives, NGOs and think-tanks, entrepreneurs and consultants who, through their coordinated efforts, have made it possible for the ultra-rich to join the international climate debate centred on the UN negotiations.” It is not only the ultra-rich themselves, but a collection of wealthy, educated individuals who all believe in the same mechanisms, who are supporting the story of the ultra-wealthy as climate heroes and implementing their policies in government accords.

A key player on this scene is the consulting company McKinsey & Company. Acting as a kind of glue between the ultra-wealthy and the political elites in many countries around the world, McKinsey is responsible for billions of dollars’ worth of consulting services to governments. What do they do? “McKinsey has an unrivalled ability to identify the latest ideas and trends, synthesise them, reappropriate them, amend them, repackage them and sell them back to its clients in the form of PowerPoint presentations.”

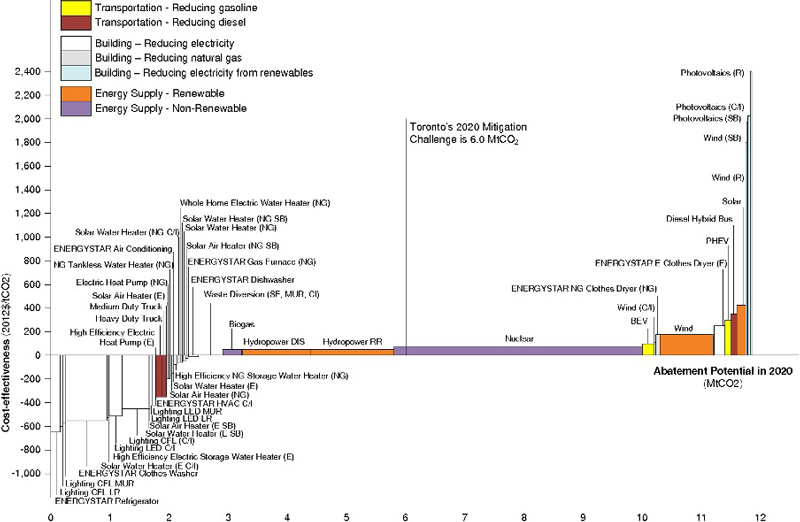

Frédérique Six, a junior consultant inside McKinsey, developed the Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC) curve to demonstrate how to decarbonise a company. These charts, or curves, tell a company which actions will most effectively decarbonise their economic activities, and the relative monetary cost of each option. In one chart, we can see the actions which cost the least and lead to the greatest carbon dioxide emissions reductions, and therefore these actions are the ones to be selected in the environmental blueprint for the company. These curves were made for all sorts of companies and states.

The MAC curve has many critics, however. In the beginning, Morena reports, McKinsey were criticised for failing to take into account certain important data in their calculations, for underestimating or omitting certain costs like non-financial costs, for making extravagant and/or unverifiable projections, and for failing to reveal just how they went about calculating the information displayed in these curves. Fabian Kesicki and Paul Ekins discuss some of these flaws in their journal article here.

Conference of the Parties, COPs around the world

Where is this message of green capitalism communicated? Now that these economic and political elites have created a ‘climate calendar’ of yearly meetings and discussion papers about the response to climate change, it is very difficult to exist as an activist outside of this calendar, and still have impact. It is at these meetings that decisions are made, even if they are made with the underlying blueprint developed in accordance with the interests of the mega-rich.

Greta Thunberg now attends the World Economic Forum in Davos, which is one of the places where climate policy is discussed among politicians worldwide. Thunberg must attend this conference, because it is there that decisions are made. However, the other participants are unlikely to listen to her real views. Not attending would be akin to having no voice, and she would lose the little impact she might have. It’s an impossible situation. Morena writes, “Thunberg’s presence in Davos is symptomatic of a wider difficulty in existing outside the arenas – UNFCCC, IPCC, One Planet Summit-type climate gatherings – which, taken together, make up what is commonly referred to as the “climate governance regime”. […] The climate movement has become structurally dependent on these elites and their political agenda.”

It’s no longer possible to have an impact as a climate activist and at the same time not attend the very meetings where countries agree on climate response mechanisms. At the COP21 in Paris in 2015, according to interviews conducted by Morena with climatologists who attended the meetings, those who could possibly have spoken out against the propositions in the Paris Agreement were silenced by a group of communication experts. They received the message: if this agreement does not pass, “you cannot exonerate yourselves from the possible consequences of your negative statements.” In other words, if an agreement is not reached, it is your fault for not supporting it – whether it represents a true and meaningful emissions reductions plan or not.

In order for the Paris Agreement and the technological and market-based mechanisms to become popular, many foundations, think tanks and experts sponsored by the ultra-rich began communications campaigns to incorporate their vision into the climate movements. They had to spread their message and their vision far and wide, so that their agreements were seen as the only possible logical and acceptable solution for all countries around the world to decarbonise their economies.

David Fenton is an expert in public communications who runs a business in the US called Fenton Communications. He specialises in public relations campaigns on environmental, public health and human rights issues. Morena uses Fenton’s analysis to detail the mechanisms through which these communications experts spread the message of the ultra-rich.

Common psychology will tell us, according to Fenton, that the brain is capable of thinking only about messages that are either true or false. Thus, we need to be either FOR or AGAINST climate action. By simplifying the message, we can create two groups of people: those who are for doing something about climate change, and those who are against it. In this way, those activists who support other means of climate justice and emissions reductions can be neutralised by reminding audiences that everyone is on the same page: we all want emissions reductions, and it just so happens that market mechanisms and technology is the way that we, the elite, have agreed to go about it.

It became possible, and is still possible, for companies to paint the picture that they are active and engaged in the fight against climate change, yet continue business as usual. When the ability to distinguish between different ‘shades’ of green is removed, everything that is painted green becomes of equal value – whether this is true or not.

The urgency of the situation is another mechanism that is used to push forward a singular agenda for fighting climate change. Because we ‘don’t have time to think of other solutions’, we need to use the ones that we currently have, i.e. markets and technology, so that we can confront the crisis. This of course ignores the many hundreds of other, well-elaborated solutions that are more democratic and more effective at responding to the ecological crisis.

How do the rich prevent change?

Hervé Kempf, a French journalist, wrote a book in 2007 called “Comment les riches détruisent la planète (How the Rich Destroy the Planet).” More than 15 years ago, the same issues were at play, and it became clear how the ideas that certain people were pushing onto the society were preventing the collective from making the decisions that were, and still are, necessary, to respond to the ecological crisis.

According to Kempf, there are four ideas that block us from changing:

- The belief in growth (especially economic growth)

- The idea that technological progress will resolve ecological problems

- The idea of the fatality of unemployment

- The common destiny of the US and Europe (and we could add, other allies).

These ideas represent a certain view of the world that is completely opposed to any kind of ecological measures. Continued economic growth, and growth in consumption, is not possible in a world with finite resources. Technological progress cannot attempt to understand, replicate, and modify natural systems that took thousands of years to evolve. All current trials of technologies don’t show much promise in a time frame that we would need them, and require immense resources to run and deploy. That’s not to mention the risks involved in their deployment. Unemployment is a way for the capitalist system to ensure low wages to keep the costs of production down. However, the green transition involves the creation of many, many jobs across the world. Finally, the US and Europe are not on the same path: Europe follows most of its climate pledges, the US does not (or does not even engage in making pledges). Similarly, New Zealand following these Western powers prevents any kind of original and local solutions from emerging.

If these ideas are the ones that are dominant, and are stopping us from changing, it seems evident that we need new ideas. We have them. However, they are not taken up. Why? Kempf provides several reasons:

- The elites (our politicians, CEOs, investors, and many academics) are trained in economics, politics, and engineering. Not in ecology. It’s a natural human bias to tend to minimise the impact of the things we don’t understand.

- We favour an economic representation of everything in society and in nature.

- People continue to give responses like, it’s not a big problem, we have technology and science to save us

- The way of life of rich people is cut off from the reality of climate change and social inequality. They don’t see the problem, so cannot imagine what the impact is.

- The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 meant that capitalism had a chance to sink its roots deeper into societies the world over, and any other forms of social organisation were ignored for some time.

We can see these ideas playing out on an everyday basis. When it comes to constructing a new road, Governments prefer to look at a cost-benefit analysis, rather than an ecological impact report. They think it’s possible to weigh up the cost of a project against the damage that might be caused to the environment, when in fact these are two completely different things. We also see that very, very few politicians and CEOs have any training on climate change and the ecological crisis. If they don’t understand something, of course it will not be seen as particularly important. And finally, a belief in the new ‘God’ of science and technology coming to save us continues a narrative of non-action, rather than taking necessary steps today to solve the problems we face.

The problem of ‘truth’ in the climate debate

After having read this article, you might be thinking: well, how do I know what is true anymore? How do I know who to believe?

That is a very difficult question to answer. Almost everything in our current economic and social system is sponsored or supported by a certain agenda or viewpoint on the world. It’s very, very difficult to know what to believe.

I find it useful to think about the following questions when I come across a climate policy or suggestion:

- Who is behind the idea? What is their experience – are they an ecologist, an economist, a physician, a politician, a doctor…? Does this experience relate to the proposition they are making?

- Who finances this person, or this organisation? Are they sponsored by big business, wealthy entrepreneurs, Jeff Bezos/Bill Gates…?

- Where was this research or policy produced?

- What happens when I perform an internet search on this idea? Or on ‘criticisms of x…”? Are there strong counter-arguments to it?

The other thing to keep in mind is that there is no ‘true’ solution to climate change. There isn’t even a ‘solution’ to it, because the problem is so complex and so widespread throughout societies across the world that no one mechanism or set of policies will enable us to respond adequately.

Conclusion

What have we learned about the ultra-rich? That their class interests (money and power) and their climate anxiety (about losing these things) have encouraged them to act in a coordinated manner to impose a certain narrative of climate change and climate solutions.

Morena concludes his book: “They may talk to us, feigning emotion, about apocalypses, collapses, a burning planet and the point of no return, but their climate emergency is not our emergency, and even less so that of the vulnerable populations already hit by the effects of global warming. It is the rich who are destroying the planet.”

It’s important to highlight this point: “their climate emergency is not our climate emergency.” Their reasons for fear, the things they will lose, and the things they want to protect are not the same as the majority of people on this planet. And when we understand this, we understand why they believe that market mechanisms and technological inventions will save us from climate collapse. The market mechanisms are in place so that they can continue to generate wealth from their investments, and the technological approach enables them to build a future where they retain their power.

Morena writes, “The climate policies implemented for their benefit – based on tax breaks, tax credits, guaranteed loans, public/private partnerships, voluntary commitments and market mechanisms – come at a high price for society. As well as being ineffective, they unfairly place the financial risk and cost of transition policies on the community.” Instead of helping address the climate crisis, these policies put the cost of a society-wide ecological transition on the community, rather than on those who are most responsible for the destruction of living ecosystems, the loss of biodiversity, and the changing climate.

You could be part of an ecological transition where you will become happier, wealthier, and more connected to other people and to the planet. These carbon credits and technological solutions will in no way benefit you in the long term. They are mechanisms designed by those who have power and money, so that they may continue to have power and money as the climate changes and their investments and assets are threatened.

I agree with Morena’s conclusion: End of the world. End of the month. End of the ultra-rich.

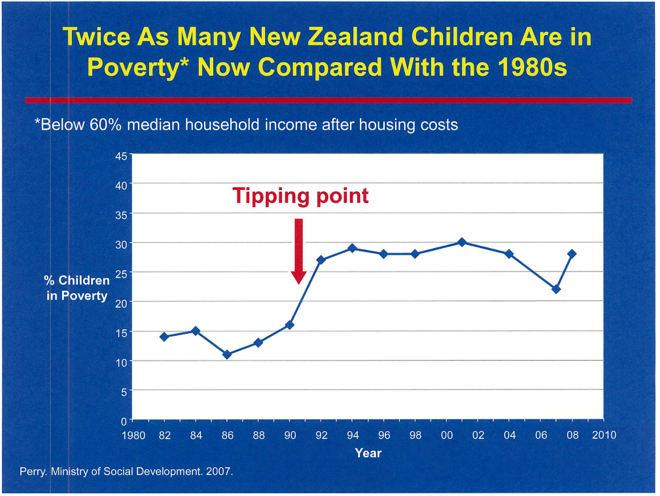

They are the same battle. Climate change, poverty, and inequality are three sides of the same problem. They certainly won’t be solved by more of the same thinking that created them.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024

Eco-emotions: eco-anxiety, solastalgia, eco-depression…

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 07/12/2023

- No Comments

- Politics

share

The way we feel when we think about climate change and environmental doom is different for each person. Some of us feel hope, others feel powerless and even depressed. What are these eco-emotions, how prevalent are they, and what can we do about them?

In this article...

- Anxiety is an extreme fear of a perceived future threat. Eco-anxiety is the fear that comes from environmental doom and an uncertain future for human societies.

- Around 59% of young people aged 16-25 are very or extremely worried about climate change around the world. This is a widespread phenomenon.

- Eco-anxiety seems to be both an emotional and a behavioural condition. It affects our mood and our ability to function in everyday life.

- Critics of eco-anxiety say that this only occurs when we don’t know the cause of our anxiety and how to act. We know what causes climate change and we know how to reduce our emissions, so we should be furious, not anxious.

- Some of the best ways to cope with eco-anxiety are taking action at a local level, and talking amongst like-minded people about how we feel.

In 2019, the term eco-anxiety became a buzzword in media across the world, with dramatic increases in the use of the term and reporting on the issue. Some years on, the term seems to have dropped from our everyday usage, but the evidence suggests that the phenomena is still widespread, and particularly affects young people.

Eco-emotions refers to the range of emotions that we can feel in response to environmental disasters that occur in our home cities, as well as responses to climate change, the future threat of climate change, and the possible extinction of species or even humanity in the future. Eco-emotions commonly include anxiety, grief, depression, anger, hopelessness, helplessness, powerlessness, sadness, and guilt.

The ecological crisis is a real threat to humanity, and it is one that has been caused by human beings themselves. It is important to state from the beginning that these emotions are normal responses to perceived threats in our everyday life. Real environmental disasters like cyclone Gabrielle in early 2023 are traumatic events for those who are involved, and it is entirely appropriate to feel a range of emotions after these events. Likewise with the threats that climate change pose to our livelihoods: worry and anxiety about the future are quite normal responses to a lack of certainty around how the future will play out.

When looking at ecological emotions, there are a range of commonly used terms which describe particular states related to our responses to climate change. These include, according to Coffey et al.:

- Eco-anxiety: the feeling that arises as a response to worsening environmental conditions, or a chronic fear of environmental collapse.

- Ecological grief: the emotion related to the losses of species and specific environmental or social conditions

- Solastalgia: the distress produced by environmental change within the local or home environment

- Eco-angst: despair at the fragile condition of the planet

- Environmental distress: the lived experience of doom and the desolation of their local or home environment

Eco-anxiety

Solastalgia and eco-anxiety are perhaps two of the most commonly used terms. Eco-anxiety is a form of anxiety, which means that it is an emotion arising out of a fear of something anticipated or something in the future. The American Psychological Association defines it as a chronic fear of environmental doom. Lise van Susteren talks about eco-anxiety as a form of pre-traumatic stress, rather than post-traumatic stress (PTSD). It is a kind of stress that arises now, in the present, but relates to a trauma which is yet to happen, something that exists in the future: climate breakdown, environmental doom, the extinction of species… She says, “We are on the tracks, the train is coming, we can hear it, we can see it, and we’re wondering if we’re going to do what’s necessary to save ourselves in time.” For van Susteren, eco-anxiety is a condition, and not a disorder. The real disorder, for her, is to not have eco-anxiety: this means that someone is not concerned about the future of the planet.

On the other hand, solastalgia is an emotion relating to the present and past environmental disasters that occur close to home. In 2003, the Australian Glenn Albrecht coined the term, and talked about seeing his country disappearing without him actually leaving it. Solastalgia is the suffering that we have in the face of climate destruction: it is watching the rivers dry up, hearing fewer and fewer birds, seeing the trees get diseases… all the small experiences in everyday life that demonstrate a changing climate and environment.

There have been a few articles about eco-anxiety in the New Zealand press, as well as some studies involving eco-emotions amongst university students in Wellington. This Stuff article laments the fact that older generations think that those who experience eco-anxiety are hysterics, and should just calm down. RNZ published a story on eco-anxiety in young people in particular, noting the experiences of some parents regarding their young children, who are experiencing distress because their favourite animals are at risk of extinction. Slightly older children are also distressed because they have realised that their future almost certainly will not be as rosy as it could have been.

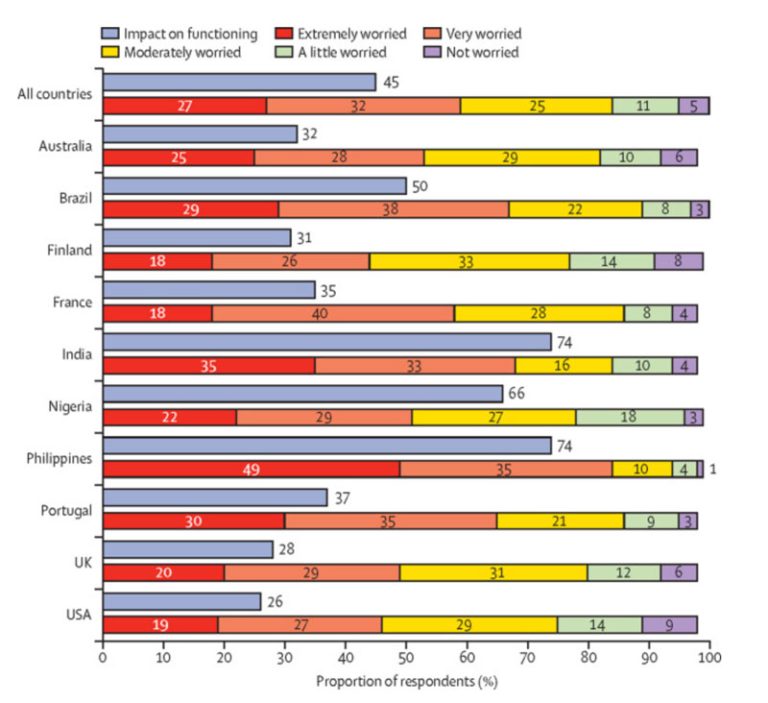

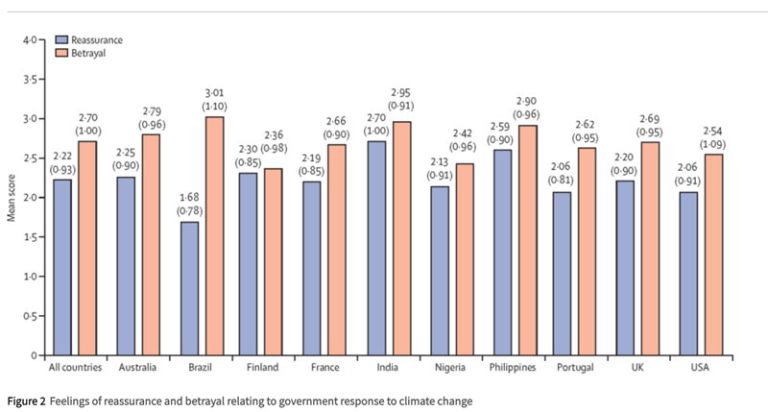

Just how prevalent is eco-anxiety, then? In 2021, a study was published in The Lancet that collated the experiences of 10,000 young people from 10 countries across the globe: “Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey” by Caroline Hickman et al.). Children aged 16-25 were surveyed from Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the UK, and the USA). They found that 59% of respondents were very or extremely worried about the impacts of climate change, and 84% were at least moderately worried. More than 50% reported feeling sad, anxious, powerless, angry, helpless, or guilty.

The researchers wrote: “These factors are likely to increase the risk of developing mental health problems, particularly in more vulnerable individuals such as children and young people, who often face multiple life stressors without having the power to reduce, prevent, or avoid such stressors.” Young people know the risks that are present and they know that their future may not be so bright, but they are quite powerless to do something about it.

There are many ways that we can respond as a result of experiencing eco-anxiety. The researchers write, “Defence mechanisms against the anxiety provoked by climate change have been well documented, including dismissing, ignoring, disavowing, rationalising, and negating the experiences of others. These behaviours, when exhibited by adults and governments, could be seen as leading to a culture of uncare.” As a result of these adult behaviours, more respondents felt betrayed by their governments than reassured by their actions.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

“The destruction of life forms every day makes me anxious. It’s also the difference between the political announcements and the actions taken to change things. This creates cognitive dissonance and a feeling of a lack of power. I can sometimes let myself be submerged by emotions. When these emotions are really present it’s difficult to have a logical discussion. We end up feeling like we don’t get across the urgency of the problem. I also put a lot of responsibility on myself to act in the right way and make a lot of effort to do certain things which makes life difficult.

I think we must welcome and accept eco-anxiety. It’s a process of mourning for a world and a way of life that is no longer possible, and mourning many, many species that are losing their lives. Action is the best way to leave the state of depression. Taking action, finding friends, and making statements about what you believe in.

I don’t want to cure my eco-anxiety, because I find it healthy.”

Interview with Lucie Lucas, in Vert.eco (translated from the French)

Does eco-anxiety stop people from living normal lives?

For Lucie Lucas, her eco-anxiety was something that motivated her to act. According to much of the research, eco-emotions are often motivating emotions, meaning that they lead to us taking more actions to prevent climate destruction. We can harness these emotions and use them to guide our actions, making positive decisions for our future and the future of our planet.

However, some research suggests that eco-anxiety can also be an emotion that has behavioural consequences: we can no longer function normally in the world as a result. This is one of the reasons why understanding eco-anxiety and its prevalence among young people is particularly important, and could be a potential problem for our societies. Certain studies claim no connection between eco-anxiety and behavioural changes; other studies such as one conducted at Victoria University in Wellington and Canberra University in Australia, claim a clear connection between eco-anxiety and some kind of cognitive impairment.

This study, published in 2021, by Hogg et al., noted that 54% of respondents experience eco-anxiety at least some of the time. Some of the common physical or behavioural responses included changes in mood (20%), unable to sleep or unable to eat (11.38%), trouble concentrating or constant rumination about how one’s actions affect the environment (6%) and an impacted ability to work or study (4.49%).

The aim of the study was to determine a scale or set of behaviours and emotions upon which we could measure eco-anxiety. The Hogg scale, as they called it, measures eco-anxiety with some reliability, and includes both emotional experiences, and behavioural changes, indicating that eco-anxiety is both an emotional and a physical condition.

In 2021, Stanley et. al looked at the impact that eco-emotions might have on our willingness to take action to stop climate change. They looked at three emotions: eco-anxiety, eco-anger, and eco-depression. They found that eco-anger was a good predictor of personal action taken to stop climate change. All three emotions were good predictors of actions taken at a collective level, with eco-depression and eco-anger being most likely to predict collective action. The researchers note that eco-anger might not be the cause of personal action, rather there might just be some relationship between those who experience eco-anger, and those who take personal actions.

Critiques of eco-anxiety

Does eco-anxiety really exist? Is it something we should be talking about, or is it just another way for us to label and categorise an experience, instead of focusing on the actions needed to respond to the ecological crisis?

The German philosopher Gunter Anders said that fear is a necessary stage we must pass through, in order to take meaningful social action. We must feel the fear for a future we do not want, before we are to really commit to living in a different way and fighting for a different future. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a kind of fear when we don’t know what the cause is and we don’t know how to respond to that cause.

This point of view is supported by Frédéric Lordon, a French philosopher and economist. In a contentious and provocative article in Le Monde Diplomatique (in French), he argues that in the large majority of cases, people are not experiencing an anxiety, but a form of fear. Anxiety is a condition which leaves us unable to act, because we are anticipating a problem which has not yet happened. He writes, “Eco-anxiety is to see the climate disaster, but to not have any idea from where this disaster comes or how to address it, to defend oneself.” Climate change, however, is a known problem, and we know what we need to do to respond to this problem: reduce CO2 emissions, reduce our consumption of natural resources, stop industrial farming practices, reduce pollution in waterways, in the ground, and in the air… There are many known actions that need to be taken. It is clear what to do to respond.

The media is presenting eco-anxiety as a new trend, and this, according to Lordon, is a neoliberal tendency to psychologise things – to make normal emotional responses to everyday life into particular psychological conditions that require ‘treatment’. This depoliticises these emotions, meaning that instead of looking at the social and political causes of eco-anxiety, we see that the individual person is at fault for experiencing these emotions and try to ‘cure’ them of their condition or disorder. It becomes ‘your fault’ for worrying about your future, rather than the fault of power imbalances and the actions of a certain few, wealthy and powerful individuals.

This in turn means that we can continue doing very little to confront the ecological crisis, because the media have neutralised the emotions that could lead to positive climate action. Instead of mobilising these emotions, they are referred to as the latest condition to plague young people and make their lives miserable, rendering them incapable of participating normally in society. These particular people need psychological interventions, to help them participate in society – the very society which is causing climate change and ecological disaster. Lordon would say that it is the society that is sick, not the individual.

“The only way to break the deadlock is to repeat the same thing over and over: there is ecocide, it is capitalist, there is no solution capitalist, therefore…

We have to put clear and distinct ideas in the heads of people about what is destroying them. That way, we can’t say we have no idea what to fight against, we can’t say we’re eco-anxious, because we know the cause, and we know what to fight.”

Frédéric Lordon

Lordon prefers to refer to himself and others as eco-furious. He is reacting to the ecological crisis, and also to the fact that very little is being done by governments and those in power to stop this crisis. Instead of being anxious because we don’t know what to do, we should be furious because we know what we need to do, but it is not being done.

A second critique of eco-anxiety asks the question, “who profits from eco-anxiety?” In an article on Vert.eco (in French), Vincent Bresson looks at eco-anxiety as a new way for certain people to make money and capitalise on the emotions of everyday people in a world which works against their interests. He notes that streaming services such as Netflix produce and buy content related to the environmental crisis. They play on the fear of the world disappearing, humans being overtaken by robots, or some calamity wiping out life on earth, to produce content that people pay to watch.

Similarly, there are many conferences and YouTube videos and talks which discuss “transform your climate anxiety into positive action” or “overcoming climate anxiety,” which are sponsored by large groups and corporates. These “gurus”, as Bresson calls them, come onto the stage and talk about how people can turn their climate anxiety into actions such as recycling, living without plastic, driving the car less, giving climate talks in local schools… They do this, instead of drawing attention to the current social and economic systems which lead to climate anxiety, and produce the ecological crisis. Instead of helping people to see that the causes of these problems are also much larger than the individual actions they are responsible for. As a result, many solutions are proposed by budding entrepreneurs looking to turn problems into solutions, such as charging $200 to spend a day in nature hugging trees, visiting a specialist eco-psychologist who will somehow make this uncertain future okay…

These two critiques draw attention to the social and political causes of eco-anxiety, and remind us that an individual is not necessarily responsible for being in a state where they fear their future. However, these critiques miss the mark when it comes to very young people. Children cannot take actions to stop climate change, yet they are coming to understand the implication of the world that they live in. This creates a very real anxiety, which cannot and should not be ignored. The child who is afraid of the elephants becoming extinct probably does not understand enough about why this is the case, and can do almost nothing about this problem. The stress and anxiety this child feels is a condition we should be concerned about, as we introduce more and more climate-related education into our schools.

What to do about eco-anxiety

If you are experiencing eco-anxiety, or any of the other eco-emotions, it can sometimes be difficult to see how to overcome this debilitating worry about the future. This is especially the case when the actions taken by governments and businesses are nowhere near the level necessary to confront the ecological crisis.

There are two things that are particularly effective as strategies to cope with eco-emotions. The first of these is to take action at the local level. This can be in whatever way you like, with whoever you like, and focused on whichever cause you feel most strongly about. For some people, this might be volunteering with a conservation group once a week to plant trees and restore a local habitat. For others it might be joining a climate organisation as the treasurer and helping with their accounting. For others still, it might be starting a climate focus-group in their business or workplace to look at how the business might be rethought, resources might be re-used, and circular principles implemented.

Taking action means that we no longer feel quite so helpless and powerless, and we begin to see that the things we are personally doing can have an impact on the lives of other people and the state of the planet. Every tree we plant, and every discussion we have with colleagues will change the state of the web of connections which forms our cultural fabric. Just as one tree helps an ecosystem to recover, one conversation, one policy adopted in your workplace will help us get closer to the systemic changes which are really needed. By acting, we leave the realm of thoughts and rumination in our heads, and take practical actions to change the world around us. And it feels great!

The second thing we can do is learn to let go of the feeling of personal responsibility for climate change. Yes, some of our actions are responsible global temperatures increasing and biodiversity loss. But unless you are Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos (or a member of this kind of wealthy elite), your real contribution to climate change is infinitesimal. Many of the decisions we make in everyday life are often forced decisions: unless we really go out of our way to live a zero-waste life, the things we buy will be packaged in single-use plastic, and there isn’t much we can do about this, unless a large proportion of consumers take action against the companies that are responsible for these choices. It’s not your fault, and your fault alone, and you cannot bare the burden of the responsibility for climate change. A series of decisions made over centuries of human action have led us to this point – and a large majority of those decisions were made when you were not alive. Climate change isn’t your fault.

Dr. Jackie Feather, a New Zealand psychologist, suggests that opening up and coming back to the present moment are also important strategies to confront eco-anxiety. Instead of imagining a terrible future situation, we can confront the present moment with honesty and look at who we are and what we are doing, and take actions to change the present. The future hasn’t happened yet, and you are not the only person responsible for how this future will play out. But the present moment – that is yours alone to create!

Matthew Adams, a psychology lecturer at the University of Brighton in the UK, emphasises that eco-anxiety cannot be fixed. It is a “normal response to a crisis or threatening situation.” His tips to cope with eco-anxiety include learning to acknowledge and accept difficult emotions, and realising that you are not alone with these emotions. Many young people around the world are feeling similarly powerless and fearful for their future.

Eco-psychologist Mary-Jane Rust talks about the loss of a connection with nature that is prevalent in many Western societies. She says, “There’s a sense of dullness in our comfortable world. We’ve lost a sense of our wild selves. You see many humans go in search of that. We create the adventure that we’ve lost.” By seeking out a connection with the world around us, and creating opportunities for adventure and exploration, we learn to love the wild – the natural environment. This in turn helps us to feel more embodied and to gain wisdom, experiential knowledge, rather than just theoretical knowledge and facts.

The website Carbon Conversations, which has recently become Living with the Climate Crisis, has a set of free resources to help people facilitate sessions where participants explore their eco-emotions and learn strategies to cope with these emotions. This is based on over 15 years of eco-psychology sessions in Oxford, England, started by Rosemary Randall and Andy Brown.

Where to get help

If you are experiencing anxiety or depression that you feel you cannot manage, it’s a good idea to get help from someone who knows and understands these feelings. Contacting a psychologist or psychotherapist near you is a good place to start. It takes courage to recognise that we might not be able to overcome these emotions by ourselves, and it takes time to accept them, but once they become a motivating force, they can lead us towards positive actions, deep friendships, and more meaningful connections with human beings and the natural world.

If you need to talk to someone, there are people ready to help you. In New Zealand, you can call these numbers 24/7:

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP)

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234

Anxiety NZ – 0800 269 4389 (0800 ANXIETY)

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Is recycling really that great?

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 30/10/2023

- No Comments

- Ideas, Politics

share

Recycling is often heralded by business and government as an effective way to combat climate change and pollution problems. Does that claim stack up? You’ll discover that in fact, reusable glass bottles are the best packaging option over short distances, and not recycling. It will also become clear that recycling is a way for companies to shift responsibility for their waste to consumers, rather than addressing the problem themselves.

Plastic brick company Lego announced recently that they are abandoning their project to make Lego pieces from recycled plastic bottles. Lego is trying to reduce its impact on the environment through changing the materials it uses to produce the bricks. They currently use acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), which needs about 2kg of petrol to make 1kg of plastic. The test involved recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) from plastic bottles, but the conclusion was, according to the company, that recycled bricks would result in higher carbon dioxide emissions and a larger environmental impact than the current process.

In New Zealand, only 29% of plastic bottles are recycled, yet the world average for plastic bottles is 50%. Consumer Magazine conducted some research in 2021 into the extent to which plastic packaging was recyclable. In New Zealand, 52% of plastic packaging was found to be, in practice not recyclable, despite some claims made by manufacturers. This result was the second worst (behind Brazil at 92%) among the countries tested. In Australia, only 14% of plastic packaging is not recyclable.

Despite this, New Zealanders still believe that recycling is one of the most effective actions to combat climate change. In some research into environmental attitudes by IPSOS in 2022, 62% of respondents are already recycling, and a further 33% are likely to start recycling in the next year, totalling 95% of the population who are now likely to be recycling. However, 50% of New Zealanders believe that recycling is one of the top three actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In actual fact, recycling comes in at 60th place, behind numerous other actions that are more effective.

As Lego have found out, recycling plastic isn’t exactly a carbon-friendly process. It involves the emissions of carbon dioxide in processes that transform the plastic from bottles into plastic that is strong to make Lego bricks. Recycling is a process which involves the addition of energy in order to transform one thing, into something else. As we will see, reusable packaging is more environmentally-friendly than recycling.

Plastic Recycling

In 2019, plastics generated 1.8 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – 3.4% of global emissions. 90% of these emissions came from the production of plastic, because plastic is made through using fossil fuels like petrol. The OECD believe that by 2060, the impact of plastics is set to more than double, from 1.8 to 4.3 billion tonnes of GHG emissions.

In 2019, researchers from the University of California looked into the relative emissions of different ways of treating plastics. They concluded that it wasn’t recycling that had the largest impact; rather, using 100% renewable energy in the production process was the most effective way to reduce plastic emissions, by 51%.

The researchers analysed four different strategies:

- Replacing fossil-fuel plastics with bio-plastics, in this case made from sugarcane.

- Using renewable energy in the production process (using wind power and biogas).

- Recycling plastics

- Reducing growth in demand from 4% per year to 2% per year.

They report, “Our study demonstrates the need for integrating energy, materials, recycling and demand-management strategies to curb growing life-cycle GHG emissions from plastics.” In an interview with the University of California to release the article, the authors explained what they meant. “We thought that any one of these strategies should have curbed the greenhouse gas emissions of plastics significantly,” author Sangwon Suh said. But they didn’t. “We tried one and it didn’t really make much impact. We combined two, still the emissions were there. And then we combined all of them. Only then could we see a reduction in future greenhouse gas emissions from the current level.”

What this study shows is that recycling by itself has very little impact on the emissions generated by plastic. It is only when combined with other changes, including reducing the growth rate of our consumption of plastic, that we see an overall impact.

Plastic is a good material, economically speaking, because it is strong, lightweight, cheap to produce, and easy to make. That is why many companies use plastic, for construction, packaging, everyday items, and more. However, plastic is incredibly damaging to the environment, and in many cases today requires fossil fuels like petrol to produce. We should also be asking whether plastic is the material to be using in an ecological future. Is transitioning to a ‘circular economy’ of plastic recycling even a good idea?

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Is plastic recycling part of an environmentally-friendly future?

Chelsea M. Rochman, Mark Anthony Browne, and other scientists make the case for classifying plastics as hazardous waste materials, and not solid waste, as they are currently. This is for multiple reasons. Firstly, plastics break down slowly in the environment, where they gradually make their way into food webs of small animals such as fish, invertebrates, and microorganisms, which ingest small bits of plastics called microplastics. When microplastics enter an organism’s tissue, they cause harm, such as tissue degradation and cellular dysfunction. It is estimated that human beings ingest up to 5 grams of microplastics per week.

Further, the ingredients in plastics, such as monomers, polystyrene, polyurethane and polycarbonate can be carcinogenic – they can cause cancer. Polyethylene, however, which is used to make plastic bags, is often thought to be safer. However, even these plastics can become dangerous when they pick up traces of pesticides, and end up disrupting key physiological processes in the body. Plastics also contain endocrine disruptors – molecules that stop some of the functions of the endocrine system, leading to cancer, thyroid disruption, and other non-communicable diseases.

The authors note that the same approach was used to clean up the atmosphere of Chloroflurocarbons (CFCs) some years ago: they were classed as hazardous materials, and began to stop being used, and when they are used, they are treated with extreme caution. Rochman and Browne therefore call for the most harmful plastics to be replaced by safer materials, and then for a closed-loop recycling of these safer materials.

Currently, 430 million tonnes of plastic are produced yearly, according to the United Nations Environment Programme, which is more than the weight of all human beings on the planet (390 million tonnes). Globally, 95% of all plastic used in packaging is disposed of after one use, and one third of this is not collected – it therefore enters the environment unmanaged, and causes pollution.

The best solution to waste management problems such as this is to not produce the waste in the first place – especially as a huge proportion of plastic packaging is used once and then disposed of. There are alternatives to this packaging that exist, for example, selling items in bulk, or in reusable containers, which have much lower emissions, and do not produce waste. The pollution problem with recycling schemes is the leaks in the system: every time plastic is not thrown away into a bin, it enters the environment and is then incredibly difficult to clean up, as it begins to affect other animals and plants.

What about glass and aluminium cans?

In 2020, Zero Waste Europe conducted a study to measure the difference in emissions between different types of packaging. They found out that in most cases, reusable glass bottles are the best option.

Recycled glass bottles require 75% of the energy used in the production of new glass bottles. However, glass bottles can also be washed and re-used. Reused glass bottles produce 85% lower emissions than single-use glass bottles, 75% lower emissions than plastic (PET) and 57% lower than aluminium cans. However, emissions for glass per unit of packaging are consistently 3-4 times greater than for plastics and aluminium.

When comparing reusable glass bottles to single-use PET plastic bottles, the glass bottles are preferable. Despite having much higher initial emissions, gradually the emissions balance out when the glass bottles are reused. However, this is only the case with smaller bottles. 2-litre plastic bottles and re-used glass bottles have approximately the same emissions.

Looking at aluminium cans, reused glass bottles seem to win again. After only three uses, glass bottles have lower emissions than single-use cans.

Transport distance also plays a role in the emissions involved in a particular type of packaging. With distances of more than 100km, reusable glass bottles have higher emissions than cartons or bags in a box, because of the transport of the bottles to be cleaned, refilled, and sent back to the distribution point.

In sum, the authors conclude that 76% of studies they looked at showed that reusable packaging is the most environmentally friendly option. Recycling is more energy intensive than reusing packaging, and recycling involves a new input of energy each time, whereas the effects of reusing packaging are balanced out over multiple uses. The more something is reused, the lower the total emissions for this type of packaging.

Is recycling a worthwhile behaviour, then?

Recycling is a behaviour done, in most cases, by the consumers themselves. When you buy a bottle of Coca-Cola, or a can of peaches, it is up to you to make the choice whether to recycle or not. This of course depends upon the recycling facilities in the area where you are using these items: if you are in a park with no recycling bins, the bottle of Coca-Cola probably won’t end up being recycled; when you’re at home, the tin of peaches probably will be recycled.

This is a good and easy solution for companies. They do not have to take any responsibility for their products, and the impacts of the packaging that they use. If something is not recycled, or is found in the environment somewhere, it is because a careless consumer put it there – not because the producer made a product in a plastic bottle. The possibility that their products can be recycled is both a selling point and a way to shirk responsibility. In the mid to late 1970’s, Coca-Cola switched from reusable glass bottles to plastic bottles, which were more light-weight and cheaper to produce. Coca-Cola and Pepsi were among the founding members of Keep America Beautiful, an organisation aimed at reducing the amount of waste thrown into the environment. The result? Cheaper costs of production for Coca-Cola, and advertising campaigns placing the responsibility on those who drink these beverages, rather than the company that produces them.

As we have seen, reusable glass bottles are one of the most carbon-friendly packaging options. Recycling is a process that involves adding a lot of energy to transform the old item into a new one. Reusing packaging means that we must simply clean it, and then use it again.

How do I decide which packaging is best?

For most of us, the most effective action when it comes to packaging is to follow these simple rules, in order:

- Does this item I am purchasing need packaging? If not, don’t use it or don’t buy a version of it with packaging. For example, buy loose apples rather than plastic-wrapped ones. Avoid packaging wherever possible.

- If the item needs packaging, can I use a glass bottle or jar to buy the item? Most pantry goods, as well as cleaning liquids, can be bought in bulk in this way. You can get flour, oats, soy sauce, olive oil, laundry detergent, and more, and use reusable glass jars.

- If the item cannot be bought like this, is there an option which doesn’t involve plastic? For example, buying soap wrapped in paper rather than plastic, jam in a glass jar rather than plastic pot, etc.

- Finally comes the choice of recyclable packaging. Which among the options involves recyclable packaging? This is sure to be better than single-use throw-away plastic.

As we have seen, there are many alternatives to recycling, and purchasing items in recyclable packaging is a good action, but by no means the most effective way to reduce emissions.

To have the most impact, the companies producing goods must change the packaging and distribution of the goods they are selling. Consumers are not the ones responsible for this packaging, nor are they able to start buying in reusable jars if the producers do not sell their products in this way. By pointing out the inefficiency of recycling to your favourite brands on social media, and choosing to shop at places where reusable containers are welcome, we can force companies to change their packaging.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

4 ways to think about the economy

Big questions: Economics

What actually happens in the economy? And how do our representations of the economy influence the way we try to solve the problems that we have identified? Are there alternatives to this dominant neoliberal paradigm, which isn’t working? These key questions will be answered here.

New Zealanders have just elected a new Government for the next three years, led by the National Party. As Toby Boraman remarked on The Conversation and RNZ, “Labour out, National in – either way, neoliberalism wins again.” The orthodox and dominant economic thinking in New Zealand has for some time been neoliberalism. In 2021, Branko Marcetic wrote an article for the Jacobin entitled, “The New Zealand “Socialists” Who Govern Like Neoliberals” with exactly the same message: New Zealand’s political parties, and the economists that support them, might claim to wear different colours, but underneath they’re exactly the same.

This isn’t the case everywhere in the world, although dominant economic, scientific, and technical thinking is becoming more prevalent in many countries. Markets, competition, free trade, and cut backs vs spending are not the only way to look at the economy. Nor are they the only instruments a government has at its disposal to respond in times of need.

Liberal economists and financial markets

In 21st century western societies, economists are constantly making predictions and analysing the forces of the market, in order to determine what our lives will be like. You would be justified in thinking that these market forces, in particular the financial markets, are the direct determinants of the wellbeing of our citizens.

This is only partially the case. Whilst financial markets have become some sort of ruling deity for governments and businesses, where every decision is calculated so as to not displease these markets, they are not the only way to look at the relations between people in a society. I’m sure you’ve heard yourself referred to as a consumer, and those companies who make the things you buy as producers. You exchange money and goods with them inside a market, and this forms the basis of the relationships you have, besides those with your family members, as an adult in society. There are, however, other relationships going on, and other exchanges being made, which are also economic in nature, but which are not best carried out in this model of a free market.