Stories of ecological transition: Ebène l’Adelphe

1st lesson : when adults tell me everything is fine, I should probably worry

2nd Lesson: just "ecology" is white dude ecology

Well, about transportation, I am now in a dead end : I did my research about alternatives to the plane but it was not very successful. If you know reasonable options, please, let me know ! Reasonable means for my family : a travel mean over the summer vacations (1 month) and within 6000€ (ticket plane back and forth).

There you go. I had become a feminist and a radical socialist and ecologist. Those 3 fights were all important to me, and despite my belief that ecology embraced them all, I did not see the expected convergence in ecologist groups. Moreover, when I asked my activist peers what was ecology for them, many didn’t quite know, there was no consensus. I was quite disappointed about those people (I am not gonna lie, there were mostly white rich cis dudes) fighting for something they could not quite define. For me, ecology was about links between living beings, so if inter-human solidarity was dead, how could we claim to take care of our connection with the rest of the living?

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

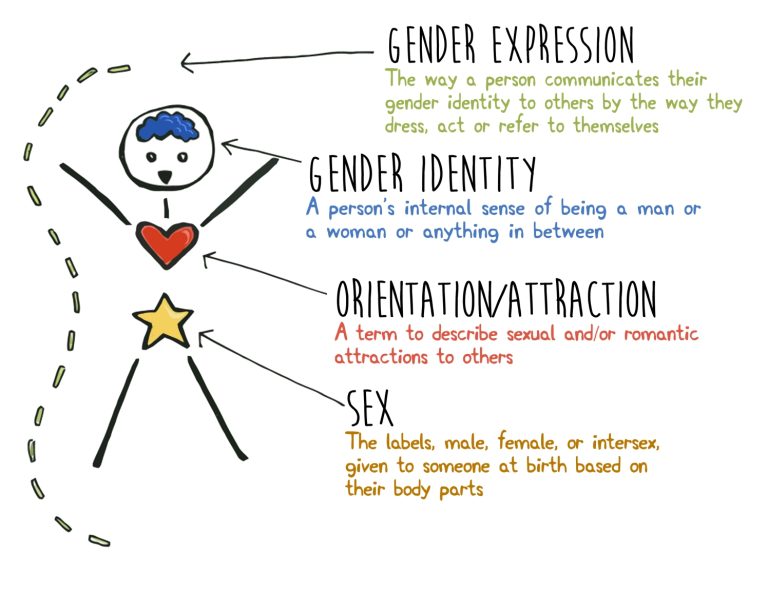

3rd Lesson: Intersectional queer ecology, alias ecofeminism

Bibliography

(1) Lefebvre, Olivier, Letter to Doubting Engineers, l’échappée, 2023.

(2) Preciado, b. Paul, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics, Points Feministe, Paris, 2021.

(3) Wittig, Monique, The Straight Mind, Boston, Beacon Press, 1992.

(4) Lovelock, James, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, Oxford University Press, 2000.

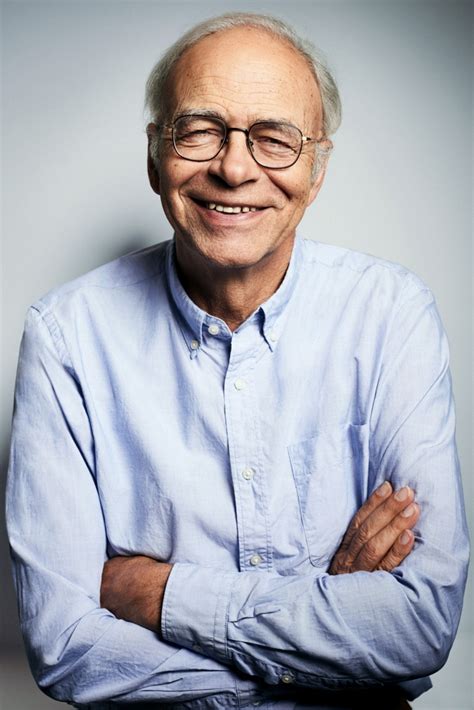

(5) Singer, Peter, Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals (1975), Melbourne, Ecco Press, 2001.

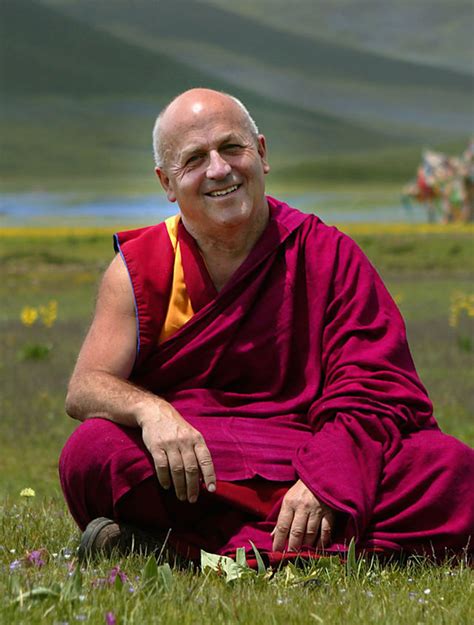

Ricard, Matthieu, Advocacy for Animals, Allary edition, Paris, 2014.

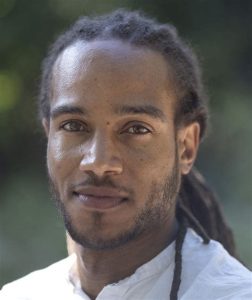

(6) Ferdinand, Malcom, Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World, Polity, Paris, 2022.

(7) Hoskin, R.A. Femmephobia: The Role of Anti-Femininity and Gender Policing in LGBTQ+ People’s Experiences of Discrimination. Sex Roles 81, 686–703, 2019.

(8) Herstory: oncept created/diffused first by the feminist journalist Morgan Robin

(9) Burgart Goutal, Jeanne, Being Ecofeminist – Theories and Practices, L’échappée, collection versus, 2020.

(10) Haraway, Donna, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

(11) Preciado, b. Paul, Dysphoria Mundi, Grasset, Paris, 2023.

(12) La Poudre with Lauren Bastide Episode 126: Myriam Bahaffou

Conversations écoféministes, Karina Kochan, Léa Chancelier, Jasmine Marty, Capucine

Néotravail #20: Des Paillettes sur le Compost de Myriam Bahaffou – Les coups de ❤️ d’Hélène & Laetiti

Avis de Tempête S2 E5 – Pratiquer les éco-féminismes depuis les marges

Book : Bahaffou, Myriam, Des paillettes sur le compost : Ecoféminismes au quotidien [Glitter on the Compost: Everyday Ecofeminisms], Le passager clandestin, 2022.

(13) Hooks, Bell, Feminist theory : from margin to center, Cambridge, MA : South End Press, 1952.

(14) Website of the association https://www.labodesresistances.fr/

(15) Bayeck, R. Y, Positionality: The Interplay of Space, Context and Identity. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2022.

(16) Sartre and the Existentialism, Camus and The Rebel… yes, yes, I know their are cis-white-het men, but don’t you think I need to add a bit of traditional Frenchness to this article to make it readable ?

(17) Hache, Emilie, RECLAIM, Anthologie de textes écoféministes, Editions Cambourakis, 2016

(18) Neimanis, AstridA, Hydrofeminism : becoming a water body, https://philo.esaaix.fr/content/hydrofeminisme/hydrofeminisme.pdf

Our Stories of Ecological Transition series puts a spotlight on inspirational people who have changed not only who they are, but how they treat the world. They've done this with courage and strength, and their stories help us all to see the ways we could change, too.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024

Guide to an eco-friendly Christmas

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 21/12/2023

- No Comments

- Ideas

share

In amongst the turkey, ham, barbecued meat, plastic toys, wrapping paper and gifts that you didn’t ask for, lies the desire for a Christmas where the main aim is not to consume as much as possible. This special day is for spending time with friends and family, whatever your religious beliefs. It’s also a time of year which we don’t have to dread – if we decide to choose sobriety over hyper-consumption.

Image: AI-created on perchance.org

What can we do to make our Christmas eco-friendly, and more about people than presents? Here are some of our best tips for the holiday season.

1. Have a vegetarian Christmas

Switching your meals from meat-based to plant based is one of the most effective actions you can take to lower your carbon footprint and the resource impact your food has on the planet. By choosing to skip the turkey and sausages, and instead opting for a vegetarian burger patty, a vege lasagne, or roasted or grilled vegetables, you will be reducing the ecological impact of your Christmas meal. This choice will also have a positive impact on your health!

2. Minimise the gifts, make your own, and wrap them in a paper bag

Instead of giving gifts from each member of the family to every other one, decide to have a Secret Santa system where each person gets a gift for one of their family members. Not only does this simplify your Christmas gift-giving, it also cuts down on wrapping, plastic packaging, and ending up with too many gifts that you don’t really need. Opt to put your present in a plain brown paper bag, instead of using wrapping paper with a plastic layer on it, which often cannot be recycled. Fold the top of the bag instead of using cellotape, and write a message on the bag with a felt-tip pen. As for the choice of gift, making them yourself, or choosing something without plastic packaging, such as experiences, gift vouchers, and second-hand objects, are effective ways to reduce the waste produced at your Christmas party.

3. Avoid online shopping, instead use local stores

Instead of buying gifts from the other side of the planet, and giving your money to global billionaires like Jeff Bezos, choose local stores who will benefit from your purchases, just as you will benefit from their local products. Choose bookstores not billionaires, shop local, and other such campaigns point to effective ways to reduce transport emissions and support community businesses. The ecological transition is not only about carbon emissions, it’s also about creating a just and fair world for all. This includes challenging the wealth of global billionaires, which we cannot do whilst also shopping using their online platforms.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

4. Think twice about the Christmas tree and decorations

Although it’s nice to have a Christmas tree, the trees often come from monoculture plantations where trees are planted and grow just for the Christmas period. Perhaps worse is to have a plastic tree, unless you plan on keeping the same plastic tree for the next thirty or so years. Avoid buying more plastic decorations, tinsel, and the like, for your tree. Make some decorations with your kids or friends using paper and origami if you’re short on decorations. Only turn the lights on at night when you can actually see them to save on electricity use and power costs!

5. Decide on your Christmas convos before the day

It’s likely there’s one or two climatosceptics amongst your Christmas group, so think about other topics you can discuss with them during the day, or ways that you can talk about your sober decisions this Christmas that aren’t patronising or moralising towards them. Engaging others in a healthy discussion about their actions is good, but try to avoid blaming them. You could talk about the origins of Christmas being celebrated on the 25th of December, for example – around the celebrations of the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, and decorations of houses with leaves and branches hoping for good regrowth of the plants and food crops in the new year to come. This period of the year, in the Northern Hemisphere, is traditionally very connected with the natural cycles of the Earth.

6. Make your resolutions for 2024 ecological

Christmas is also the time of year when we think about the New Year to come, and for many, make resolutions about the things we could change in 2024. Making at least some of these resolutions related to your impact on the environment, your relationship with nature, and your efforts in restoring the natural environment, are important steps. If you are already very engaged, resolving to take time for yourself doing things you enjoy, or making other small steps towards further reconnection with nature, are good ideas. Bringing up the conversation of climate goals for 2024 could be a good idea at your Christmas party – up to you to choose, depending on the people!

A vegetarian Christmas...

Southern Hemisphere:

- Aubergines and tomatoes cooked in the oven, with optional fresh feta sprinkled on top afterwards

- Buckwheat salad with rocket, tomatoes, capers, olives, and grilled vegetables

- Lightly grilled courgette halves, on the barbecue

- Rock melon with mozzarella, honey, and balsamic vinegar, basil leaves on top

- Lentil burgers with your favourite spices, cooked rice, breadcrumbs and olive oil

- Vegetarian pizza cooked on the barbecue with your favourite toppings

- Salad with lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, fresh herbs, rocket, olive oil and lemon juice or balsamic vinegar

Desserts with local fresh summer berries are always nice, such as pies, tarts, trifle, pavlova, etc.

Northern Hemisphere:

- Oven-baked fennel, cut in half, sprinkled with salt and drizzled with olive oil

- Wok-cooked broccoli with soy sauce and ginger

- Japanese-style green beans, blanched with a sesame dressing

- Mushrooms with olive oil and garlic, served with polenta

- Roast potatoes (boil them slightly first, then roast them in olive oil and salt until golden brown)

Desserts with oranges, apples, pears, and dried fruits are perfect for this cold season – Christmas cakes, apple pies…

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024

Is recycling really that great?

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 30/10/2023

- No Comments

- Ideas, Politics

share

Recycling is often heralded by business and government as an effective way to combat climate change and pollution problems. Does that claim stack up? You’ll discover that in fact, reusable glass bottles are the best packaging option over short distances, and not recycling. It will also become clear that recycling is a way for companies to shift responsibility for their waste to consumers, rather than addressing the problem themselves.

Plastic brick company Lego announced recently that they are abandoning their project to make Lego pieces from recycled plastic bottles. Lego is trying to reduce its impact on the environment through changing the materials it uses to produce the bricks. They currently use acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), which needs about 2kg of petrol to make 1kg of plastic. The test involved recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) from plastic bottles, but the conclusion was, according to the company, that recycled bricks would result in higher carbon dioxide emissions and a larger environmental impact than the current process.

In New Zealand, only 29% of plastic bottles are recycled, yet the world average for plastic bottles is 50%. Consumer Magazine conducted some research in 2021 into the extent to which plastic packaging was recyclable. In New Zealand, 52% of plastic packaging was found to be, in practice not recyclable, despite some claims made by manufacturers. This result was the second worst (behind Brazil at 92%) among the countries tested. In Australia, only 14% of plastic packaging is not recyclable.

Despite this, New Zealanders still believe that recycling is one of the most effective actions to combat climate change. In some research into environmental attitudes by IPSOS in 2022, 62% of respondents are already recycling, and a further 33% are likely to start recycling in the next year, totalling 95% of the population who are now likely to be recycling. However, 50% of New Zealanders believe that recycling is one of the top three actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In actual fact, recycling comes in at 60th place, behind numerous other actions that are more effective.

As Lego have found out, recycling plastic isn’t exactly a carbon-friendly process. It involves the emissions of carbon dioxide in processes that transform the plastic from bottles into plastic that is strong to make Lego bricks. Recycling is a process which involves the addition of energy in order to transform one thing, into something else. As we will see, reusable packaging is more environmentally-friendly than recycling.

Plastic Recycling

In 2019, plastics generated 1.8 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions – 3.4% of global emissions. 90% of these emissions came from the production of plastic, because plastic is made through using fossil fuels like petrol. The OECD believe that by 2060, the impact of plastics is set to more than double, from 1.8 to 4.3 billion tonnes of GHG emissions.

In 2019, researchers from the University of California looked into the relative emissions of different ways of treating plastics. They concluded that it wasn’t recycling that had the largest impact; rather, using 100% renewable energy in the production process was the most effective way to reduce plastic emissions, by 51%.

The researchers analysed four different strategies:

- Replacing fossil-fuel plastics with bio-plastics, in this case made from sugarcane.

- Using renewable energy in the production process (using wind power and biogas).

- Recycling plastics

- Reducing growth in demand from 4% per year to 2% per year.

They report, “Our study demonstrates the need for integrating energy, materials, recycling and demand-management strategies to curb growing life-cycle GHG emissions from plastics.” In an interview with the University of California to release the article, the authors explained what they meant. “We thought that any one of these strategies should have curbed the greenhouse gas emissions of plastics significantly,” author Sangwon Suh said. But they didn’t. “We tried one and it didn’t really make much impact. We combined two, still the emissions were there. And then we combined all of them. Only then could we see a reduction in future greenhouse gas emissions from the current level.”

What this study shows is that recycling by itself has very little impact on the emissions generated by plastic. It is only when combined with other changes, including reducing the growth rate of our consumption of plastic, that we see an overall impact.

Plastic is a good material, economically speaking, because it is strong, lightweight, cheap to produce, and easy to make. That is why many companies use plastic, for construction, packaging, everyday items, and more. However, plastic is incredibly damaging to the environment, and in many cases today requires fossil fuels like petrol to produce. We should also be asking whether plastic is the material to be using in an ecological future. Is transitioning to a ‘circular economy’ of plastic recycling even a good idea?

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Is plastic recycling part of an environmentally-friendly future?

Chelsea M. Rochman, Mark Anthony Browne, and other scientists make the case for classifying plastics as hazardous waste materials, and not solid waste, as they are currently. This is for multiple reasons. Firstly, plastics break down slowly in the environment, where they gradually make their way into food webs of small animals such as fish, invertebrates, and microorganisms, which ingest small bits of plastics called microplastics. When microplastics enter an organism’s tissue, they cause harm, such as tissue degradation and cellular dysfunction. It is estimated that human beings ingest up to 5 grams of microplastics per week.

Further, the ingredients in plastics, such as monomers, polystyrene, polyurethane and polycarbonate can be carcinogenic – they can cause cancer. Polyethylene, however, which is used to make plastic bags, is often thought to be safer. However, even these plastics can become dangerous when they pick up traces of pesticides, and end up disrupting key physiological processes in the body. Plastics also contain endocrine disruptors – molecules that stop some of the functions of the endocrine system, leading to cancer, thyroid disruption, and other non-communicable diseases.

The authors note that the same approach was used to clean up the atmosphere of Chloroflurocarbons (CFCs) some years ago: they were classed as hazardous materials, and began to stop being used, and when they are used, they are treated with extreme caution. Rochman and Browne therefore call for the most harmful plastics to be replaced by safer materials, and then for a closed-loop recycling of these safer materials.

Currently, 430 million tonnes of plastic are produced yearly, according to the United Nations Environment Programme, which is more than the weight of all human beings on the planet (390 million tonnes). Globally, 95% of all plastic used in packaging is disposed of after one use, and one third of this is not collected – it therefore enters the environment unmanaged, and causes pollution.

The best solution to waste management problems such as this is to not produce the waste in the first place – especially as a huge proportion of plastic packaging is used once and then disposed of. There are alternatives to this packaging that exist, for example, selling items in bulk, or in reusable containers, which have much lower emissions, and do not produce waste. The pollution problem with recycling schemes is the leaks in the system: every time plastic is not thrown away into a bin, it enters the environment and is then incredibly difficult to clean up, as it begins to affect other animals and plants.

What about glass and aluminium cans?

In 2020, Zero Waste Europe conducted a study to measure the difference in emissions between different types of packaging. They found out that in most cases, reusable glass bottles are the best option.

Recycled glass bottles require 75% of the energy used in the production of new glass bottles. However, glass bottles can also be washed and re-used. Reused glass bottles produce 85% lower emissions than single-use glass bottles, 75% lower emissions than plastic (PET) and 57% lower than aluminium cans. However, emissions for glass per unit of packaging are consistently 3-4 times greater than for plastics and aluminium.

When comparing reusable glass bottles to single-use PET plastic bottles, the glass bottles are preferable. Despite having much higher initial emissions, gradually the emissions balance out when the glass bottles are reused. However, this is only the case with smaller bottles. 2-litre plastic bottles and re-used glass bottles have approximately the same emissions.

Looking at aluminium cans, reused glass bottles seem to win again. After only three uses, glass bottles have lower emissions than single-use cans.

Transport distance also plays a role in the emissions involved in a particular type of packaging. With distances of more than 100km, reusable glass bottles have higher emissions than cartons or bags in a box, because of the transport of the bottles to be cleaned, refilled, and sent back to the distribution point.

In sum, the authors conclude that 76% of studies they looked at showed that reusable packaging is the most environmentally friendly option. Recycling is more energy intensive than reusing packaging, and recycling involves a new input of energy each time, whereas the effects of reusing packaging are balanced out over multiple uses. The more something is reused, the lower the total emissions for this type of packaging.

Is recycling a worthwhile behaviour, then?

Recycling is a behaviour done, in most cases, by the consumers themselves. When you buy a bottle of Coca-Cola, or a can of peaches, it is up to you to make the choice whether to recycle or not. This of course depends upon the recycling facilities in the area where you are using these items: if you are in a park with no recycling bins, the bottle of Coca-Cola probably won’t end up being recycled; when you’re at home, the tin of peaches probably will be recycled.

This is a good and easy solution for companies. They do not have to take any responsibility for their products, and the impacts of the packaging that they use. If something is not recycled, or is found in the environment somewhere, it is because a careless consumer put it there – not because the producer made a product in a plastic bottle. The possibility that their products can be recycled is both a selling point and a way to shirk responsibility. In the mid to late 1970’s, Coca-Cola switched from reusable glass bottles to plastic bottles, which were more light-weight and cheaper to produce. Coca-Cola and Pepsi were among the founding members of Keep America Beautiful, an organisation aimed at reducing the amount of waste thrown into the environment. The result? Cheaper costs of production for Coca-Cola, and advertising campaigns placing the responsibility on those who drink these beverages, rather than the company that produces them.

As we have seen, reusable glass bottles are one of the most carbon-friendly packaging options. Recycling is a process that involves adding a lot of energy to transform the old item into a new one. Reusing packaging means that we must simply clean it, and then use it again.

How do I decide which packaging is best?

For most of us, the most effective action when it comes to packaging is to follow these simple rules, in order:

- Does this item I am purchasing need packaging? If not, don’t use it or don’t buy a version of it with packaging. For example, buy loose apples rather than plastic-wrapped ones. Avoid packaging wherever possible.

- If the item needs packaging, can I use a glass bottle or jar to buy the item? Most pantry goods, as well as cleaning liquids, can be bought in bulk in this way. You can get flour, oats, soy sauce, olive oil, laundry detergent, and more, and use reusable glass jars.

- If the item cannot be bought like this, is there an option which doesn’t involve plastic? For example, buying soap wrapped in paper rather than plastic, jam in a glass jar rather than plastic pot, etc.

- Finally comes the choice of recyclable packaging. Which among the options involves recyclable packaging? This is sure to be better than single-use throw-away plastic.

As we have seen, there are many alternatives to recycling, and purchasing items in recyclable packaging is a good action, but by no means the most effective way to reduce emissions.

To have the most impact, the companies producing goods must change the packaging and distribution of the goods they are selling. Consumers are not the ones responsible for this packaging, nor are they able to start buying in reusable jars if the producers do not sell their products in this way. By pointing out the inefficiency of recycling to your favourite brands on social media, and choosing to shop at places where reusable containers are welcome, we can force companies to change their packaging.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Geo-engineering

IN-DEPTH SPECIAL

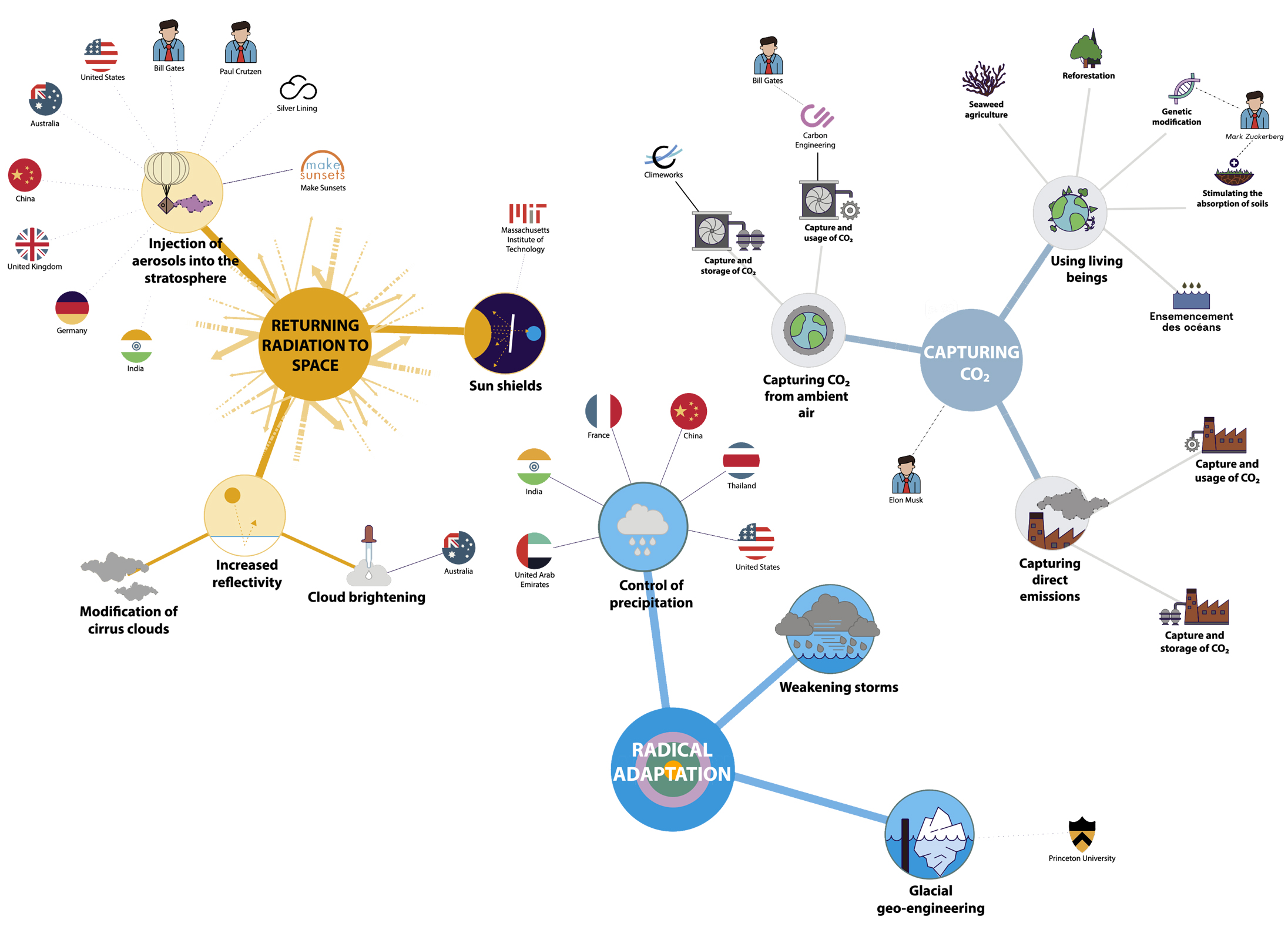

Shooting chemicals into the atmosphere to reflect the sun’s rays back into space, and adding them to clouds to make them brighter, are no longer part of our science-fiction imaginary. Geo-engineering, in its many forms, is gaining ground as a necessary and inevitable way to protect the earth and its inhabitants from the worst effects of climate change.

Geo-engineering is, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “A broad set of methods and technologies that aim to deliberately alter the climate system in order to alleviate the impacts of climate change..” Therefore, all the studies and research into ways that we can change the climate ourselves, to be protected from climate change, are projects of geo-engineering. This ranges from adding chemicals into clouds above the ocean to save the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, adding silver iodide into clouds on the Tibetan plain by the Chinese Government to modify rainfall patterns, carbon capture and storage systems in Iceland, and those researched in the UK and US (among many other countries), and at its most basic level, New Zealand’s planting of monoculture forests to capture carbon dioxide from the air.

Two forms of geo-engineering

There are two main ways of going about modifying the climate. Let’s call them the pump, and the thermostat.

The pump

The pump method refers to the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, in various ways. We try to pump the emissions that we have already created back into the ground, to store them there instead. This could be through ‘natural’ means like planting trees, or through technologies like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). We do this to reduce the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, which is one of the leading causes of climate change and the wider ecological crisis.

The thermostat

The thermostat method tries to control the average temperature of the biosphere. Human activity is causing increasing temperatures in the atmosphere, which world governments have pledged to keep below an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius. In order to reduce those temperatures, we can either make the earth’s surface shinier, so that the sun’s rays are reflected back into space, and are not absorbed by the ground here, or we can modify the atmosphere itself, so that it lets through less light from the sun, and therefore less heat energy.

The pros

There are many reasons why we might consider geo-engineering methods. If the world cannot reduce its carbon emissions before the worst effects are felt, which seems to be the case, it will need to find ways to protect life from the effects of these emissions. Geo-engineering is one way to buy us time to decarbonise, and achieve the net-zero targets that have been set. Another reason is that it is relatively cheap and easy to deploy some of these solutions, which, according to certain sectors in the economy, would be easier than decarbonising their industries. Geo-engineering also has support from a moral or ethical standpoint, with some people claiming we must do everything we can to stop the disastrous consequences of climate change. Major proponents of geo-engineering include Mark Zuckerberg (Meta), Bill Gates (Microsoft), and Elon Musk (Tesla, SpaceX, Twitter). Almost all researchers and funders of geo-engineering in the United States are white, middle-aged, and male.

The cons

Those who disagree with geo-engineering projects currently seem to outnumber those who are in favour of it, however there does appear to be some silent support among scientific, technical and economic communities. Arguments against geo-engineering point first and foremost to the risks involved in these projects. The ‘thermostat’ methods of geo-engineering could disrupt rainfall, including the Indian monsoon season, putting the lives of billions of people at risk. Furthermore, once you start injecting clouds or modifying the atmosphere, you cannot stop. Some models predict up to 800 years of continuous climate intervention to avoid a termination shock where world temperatures increase by around 4 degrees in 10 years, rather than 100 years. These projects require enormous amounts of energy, water, and in some cases mineral resources to run, which would have to be sustained through government changes, war, pandemic, and more. There is also no current way to regulate or govern the countries (and wealthy private individuals) who may start geo-engineering projects: anyone can, at present, add sulphur to the atmosphere, and this decision will impact not just one country, but the whole planet. Likewise, once one country begins, we may enter a war of the sky, where countries vie to control the modification of the atmosphere. Geo-engineering is also another reason for climate delay and inaction, allowing us to continue to emit and pollute. Solar geo-engineering would turn the sky white, having potential impacts on mental health worldwide. Finally, we don’t actually know what effect geo-engineering will have on a large scale: all we have are experiments and models. The side effects of any project, including carbon storage, could be much, much worse. Major detractors of geo-engineering include Andreas Malm (The Future is the Termination Shock), Naomi Klein (This Changes Everything), and Elizabeth Kolbert (Under a White Sky).

Who is geo-engineering?

Mark Zuckerberg supports a company attempting to genetically modify plants, such as rice, corn and wheat, so that they absorb more carbon dioxide (The Innovative Genomics Institute in San Francisco). Bill Gates supports the start-up Carbon Engineering, aiming to increase the amount of petrol extracted from wells through carbon capture and storage technology. Elon Musk’s foundation, XPrize, has allocated $100 million USD to the development of carbon capture technologies. The United States government in 2021 allocated $3.5 billion USD to create four hubs for carbon capture and storage. The Chinese government is involved in a project called the Celestial River, aiming to artificially increase the rainfall over the Tibetan plain. Governments in Australia, the UK, Thailand, France, India, United Arab Emirates, and Germany are also involved in geo-engineering projects and/or research at some level.

And New Zealand...

New Zealand is not currently involved in any technical geo-engineering projects, however natural geo-engineering is very much part of the country’s strategy. Using seaweed to sequester carbon is being researched and carried out. Likewise, planting trees (unfortunately usually monoculture forests) is a key part of the Government’s zero-carbon strategy for 2050, with the One Billion Trees Programme. The debate on geo-engineering in New Zealand seems to be almost dead, with the Government associating any mention of the word with conspiracy theory and false suggestions that storms such as Cyclone Gabrielle were man-made.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

That's just the overview. Click on the topics below to learn more about geo-engineering.

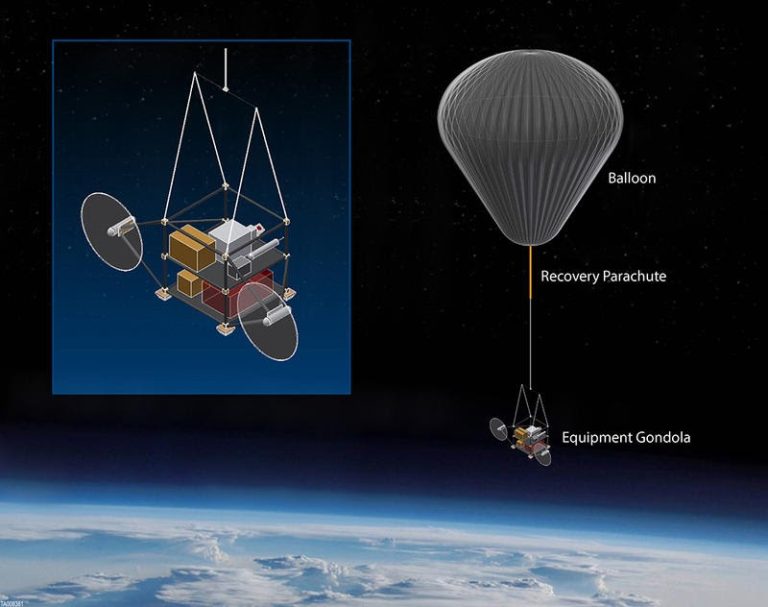

Solar Radiation and Protection

Sweden’s Space Agency, along with backers and technicians from Harvard University in the United States, were preparing to launch the pilot project SCoPEx in the summer of 2021. This project would be one of the first experimental trials of solar radiation geo-engineering in the world. Until this point, researchers had only been able to use computer models to predict what might happen, and to design potential balloons to disperse aerosols into the stratosphere.

But, after protests from indigenous groups and climate activists, Sweden’s Space Agency called off the test, citing concerns over safety, and potential risks and hazards for the Earth’s atmosphere. Blocking the sun to fight climate change would have to remain a project within the computer models for some time to come.

How does it work?

Solar radiation geo-engineering aims to inject aerosols into the upper part of the Earth’s atmosphere, the stratosphere, in order to block sunlight from reaching the Earth. Normally, a small amount of these compounds are found in the atmosphere, such as ozone, which protects the Earth’s inhabitants from excessive sunlight. By increasing the amount of these gases such as sulphur in the atmosphere, engineers hope to be able to stop the Earth from warming. This is because the radiation from the sun will be reflected back into space by the aerosols that we inject. The process is like a human-engineered, continuous volcanic eruption: when volcanoes erupt, they spew out large quantities of sulphur gases into the atmosphere. In 1991, Mt Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted, and 20 million tons of sulphur reduced global temperatures by 0.5 degrees Celsius for one year.

This is necessary because of the largely unsuccessful Kyoto Protocol, in which 147 parties, (governments), pledged to decrease emissions by individually agreed targets. We are already at 1.2 degrees of warming, and the Earth is projected to reach 1.5 degrees of warming by 2050, if not before.

The arguments

In 2006, Paul Crutzen, a scientist in Germany and the United States, published an article on stratospheric injections which broke the taboo on the topic amongst researchers. He argued that we needed to develop this technology, because it is a hugely effective way of reducing global temperatures almost immediately at relatively little cost. We needed solar radiation geo-engineering in our back pockets, if things go disastrously wrong, or if we are unable to decarbonise our economies in time. Geo-engineering is therefore the deus ex machina waiting in the wings, ready to save the planet when the time is right. It buys us time to decarbonise, and reinforces the fact that human beings are still the masters of their own destiny: innovation and technology will be able to save the day.

This position follows a technical and engineering logic: we have the technology available, we have the means, and it doesn’t cost too much, so why not develop it? Proponents believe that all technological means to fight climate change are good, if they are rationally used and controlled by world governments. Taking out 1-2% of sunlight would be enough to undo 2 centuries of fossil fuel combustion. The whole problem of climate change could go away, if we are able to design and operate this technical solution in a rational manner. And, according to David Keith in 2000, this whole process would be cheaper than climate mitigation and the reduction of emissions. $30 million USD would compensate one years’ global emissions. Proponents of solar geo-engineering now say that both emissions reductions and geo-engineering are necessary.

Andreas Malm, a Swedish researcher in climate and ecological politics, and a climate activist, wrote an article series in 2022 decrying the risks of solar radiation geo-engineering. The biggest risk with solar geo-engineering is what he terms “termination shock.” Once anyone in society – a business, a government, a wealthy private individual – starts putting aerosols into the atmosphere with the aim of reducing solar radiation on earth, the process must be continued or, theoretically, scaled down very slowly, otherwise the Earth’s temperatures will rebound incredibly quickly. To illustrate this, think about what happens when you try to fix a leak in a pipe under your kitchen sink. To stop water from going down into the pipe, you put the plug into the sink. Water builds up in the sink, but doesn’t flow down into the pipe, so you can fix it. It looks like there’s no leak any more, because you have stopped the flow of water. But, if for whatever reason, the plug is removed, dislodged, or faulty, lots of water will flow out into the pipes, making the leak worse. The same thing happens with the aerosols in the atmosphere. We can pretend that there is no longer any global warming, all the while increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. When we stop injecting aerosols, all of a sudden, the sun’s radiation would heat up the Earth by about 4 degrees in 10 years, rather than 100 years.

What reasons might cause us to stop or pause solar geo-engineering, once it was started? Another pandemic like COVID-19 might be cause to force people to stay home for months, meaning the operators and engineers of this technology couldn’t go to work, fix problems, and operate the planes or balloons that inject the aerosols. The workers could go on strike over low pay and high-risk conditions, or they could object to the risks or potential damage their job was doing to the world. China and the United States could begin a war to control the skies, each wishing to be the one determining how much of the aerosols were pumped out, and therefore how many tonnes of CO2 they could continue to emit. A rogue state could decide they wanted more, and start their own programme, meaning that the official programme of geo-engineering would need to immediately be scaled back, otherwise we could completely block out all sun light, and all living beings would die. There are numerous possible scenarios which would mean that this geo-engineering project would stop, and the effects of the termination shock would make themselves felt.

As a result of the termination shock, Malm says it would be like opening the door to a furnace on Earth. No species would be able to adapt itself to radical temperature increases in such as short space of time. Smith compares solar geo-engineering to morphine – it’s incredibly addictive, and once begun, it’s hard to stop.

Further, the modelling shows that solar geo-engineering would disrupt current climate systems, meaning the possible end to the Indian monsoon season, affecting the possibility of life for more than 2 billion people. The Earth’s overall climate would become more even – the tropics would overcool, and the poles would over-heat, according to the models. Some researchers, such as Holly Jean Buck, argue that this is a tool for equality and peace – if we all have the same climate conditions, how can we complain? I’m not entirely sure we would find anyone in the tropics who thought that their inequality with the West could be fixed by making the weather patterns of their region more like the United States and Europe…

Those who argue for solar geo-engineering make a big assumption, which Malm points out. They assume that the technology will be rolled out and managed in a rational, controlled, and pre-determined manner, and that it will remain this way for the up to 800 years of solar radiation blocking necessary to cool the Earth. But, if the world was rationally run, we would not need geo-engineering in the first place. The threats of global ecosystem collapse from the 1970’s would have been heeded, our economies decarbonised, and crisis avoided, well before getting to the point of needed to engineer the climate. Someone, somewhere, must steer the planet from harm just at the right time, with the right amount of action.

Would the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) be able to do that? Or perhaps the United Nations? Or the United States Government? Let’s ask another question: do states currently listen to and follow the directives of the IPCC? No, because again, if they did, emissions would be radically declining and we would not have crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries. We cannot expect such things to happen if we start geo-engineering, either.

Other risks include the fact that the sky will turn a milky-white colour, for the duration of the programme; disrupted climate systems across the globe; potential crop losses as a result of reduced sunlight for plants to grow; collapse of the rain systems across the globe; solar power plants producing less electricity; ozone depletion; air pollution and therefore human health consequences; more acid rain; the coagulation of sulphates in the atmosphere, and more. What’s more, climbing temperatures is one of the major reasons currently to decarbonise, and by masking this problem, we could lull ourselves into thinking that further carbon emissions are acceptable.

These effects sound just as bad, if not worse, than the effects of the climate change and global warming that solar radiation geoengineering is attempting to solve. It would seem the only rational question is, “why not just reduce our emissions?” It is a safe and effective way of responding to climate change. If done well, it will reduce inequalities, improve mental health, reduce waste, reduce habitat and species loss, and more.

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

The United Kingdom company Drax is promising to be part of a sustainable energy revolution in the UK. Instead of burning coal, Drax has reconverted its factories to burn biomass instead. Biomass is a fancy word for wood chips. Through a legal loophole, by burning wood instead of coal the company avoids its emissions being counted as part of the national emissions total. The UK, through Drax’s power, can reduce its emissions without actually reducing them.

Drax claims that their wood chips are sustainably sourced from offcuts and sawdust in wood factories. This, however, as the New York Times has investigated, is not the case. Drax cuts down forests in the United States and Canada, some of which are primary growth forests (those that have never before been cut down for human use), and ships the trees to the United Kingdom to be burned at their plants. Drax are also researching Biomass Energy Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), so that the carbon dioxide released from burning the wood chips is captured and stored in the earth, rather than released into the atmosphere. They hope to build two power stations by 2030, each capable of removing 8 million tonnes of CO2 per year. That’s equal to 1.6% of the UK’s national yearly emissions. As yet, however, despite calling their enterprise sustainable, they continue to cut down trees and burn them, releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

This is just one example of how carbon capture and storage is being used in conjunction with other supposedly sustainable methods of energy generation to “reduce” carbon emissions in the world’s largest economies. The largest project of carbon storage is the Orca factory in Iceland, run by the Swiss company Climeworks. The factory currently occupies 1,700m2 of land, filled with fans to capture the carbon dioxide in the air. The gas is liquefied then stored one kilometre underground in basalt rock. The cost of this project sits at $15 million USD, and the factory currently sucks out 4,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. That’s equivalent to three seconds of global emissions. Climeworks want to capture 1% of world emissions by 2025. Based on current progress, the dreams of millions of tonnes of CO2 being sequestered every year seem very, very far off.

How does it work?

There are two main methods of removing carbon: collecting carbon dioxide directly from chimneys (Carbon Capture and Storage, CCS), or sucking the gas out of the air (Direct Air Capture, DAC).

Capturing carbon directly from chimneys involves attaching a capturing device to the infrastructure already present, such as the wood burning factories of Drax in the UK. Then, the carbon dioxide is compressed, and needs to be stored somewhere deep in the earth where it is not going to be released.

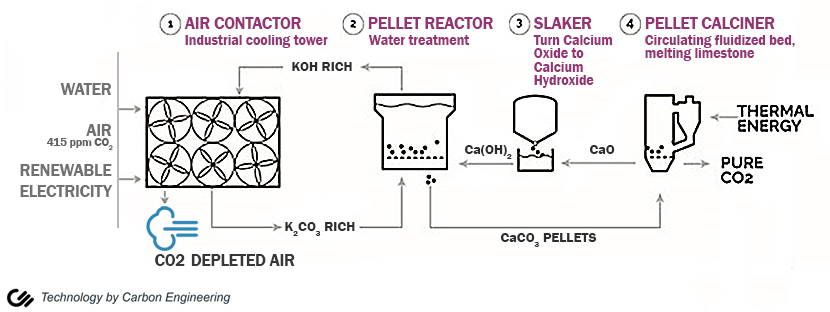

Capturing carbon from the air involved hundreds of huge turbines, sucking in air and capturing the carbon dioxide as the air passes through. These turbines are constructed in an industrial cooling tower, which pumps water around to stop them from overheating. The carbon dioxide in the air is converted into potassium carbonate, through a reaction with potassium hydroxide sitting on thin plastic sheets within the turbines. These pellets of chemical salt undergo further chemical reactions to produce pure carbon dioxide.

Today, this technology is primarily used by petroleum companies. They extract carbon dioxide from the air, in order to pump it back into the oil wells and force the oil to the surface. They use the emissions of burning fossil fuels in order to extract more fossil fuels…

In a trial in Iceland with the first carbon being injected into the ground, the researchers on the CarbFix project realised that micro-organisms in the rocks were feeding on the carbon dioxide being injected, meaning that injection possibilities were considerably reduced. Now, instead of injecting the CO2 at 100 degrees Celsius, it’s injected at 250 degrees Celsius, killing off all microbes, and potential microorganisms in the rocks. It’s estimated that 60% of species living 1km into the earth’s surface are still unknown to humans, but this has not been factored into the plans or risks involved, as noted by those who are using the technology.

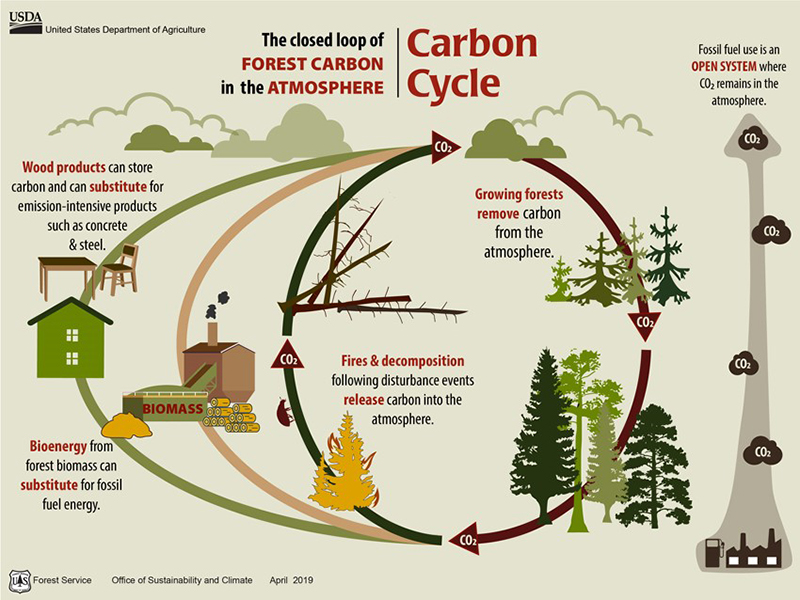

Another, more ‘natural’ method of carbon sequestration, is through using trees and other plants. New Zealand, like some other countries, has committed to planting 1 billion trees by 2028. When plants grow, they use the carbon dioxide in the air to make the organic molecules they need. These molecules of glucose are stored in the plant. The water that the plant absorbs is also taken up and converted into oxygen, which the plant releases. This process is called photosynthesis, which is part of the Earth’s carbon cycle. Therefore, trees such as the radiata pine tree are often used to capture and store carbon, because they require carbon dioxide to grow, therefore taking it out of the atmosphere. Often, the trees planted are not native trees to the area, and are planted with the idea that they will be cut down eventually. This means that we are not creating biodiverse native forests with habitats for other species; rather, we are engineering a human ‘forest’ for the sole purpose of sucking out carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

All other plants do this too – corn, wheat, and soy for example. Mark Zuckerberg supports research by the Innovative Genomics Institute, exploring how to genetically modify these crops, so that they absorb more carbon dioxide from the air: they want to make the process of photosynthesis go faster, and occur in greater quantities in the same plant. This gene-editing technology is called CRISPR, developed by Nobel prize winner Jennifer Doudna.

Using trees to suck up carbon

Using seaweed and the ocean

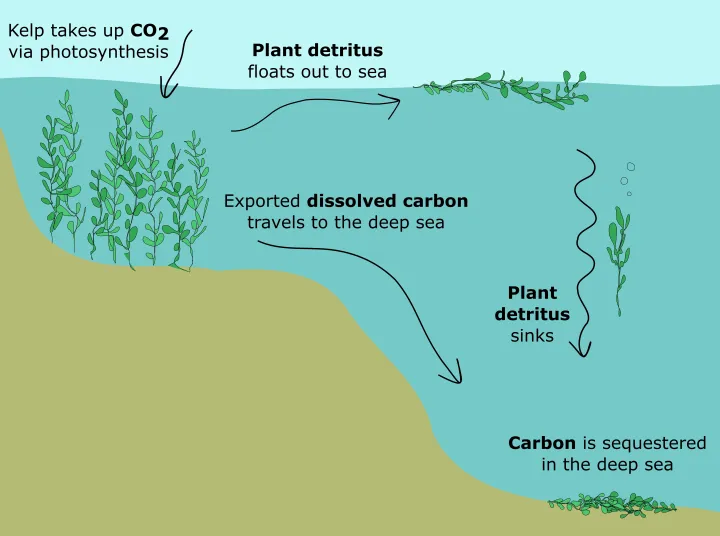

The ocean is another large storehouse of carbon on the planet. So much so that the IPCC has written a paper in their 6th cycle of reporting on Ocean Carbon Storage. According to them, over the past 200 years the oceans have taken up 500Gt of CO2, whilst humanity has emitted 1,300Gt of emissions in the same period. Not all carbon dioxide goes into the atmosphere, therefore: quite a large proportion of it ends up in the ocean. Carbon dioxide can be injected into the ocean, or we can use plants such as kelp (seaweed) to the same effect. New Zealand firm Blue Carbon is researching this method, and hopes to more effective at sequestering carbon than its land-based alternative. A trial in South Korea showed that for one hectare of algae, 10 tonnes of CO2 were captured, per year. That’s an almost insignificant amount, less than the average emissions of one New Zealander in a year.

By adding fertilisers such as iron and nitrates into the ocean, we can encourage seaweed to grow faster, taking up more carbon dioxide. There are, once again, several risks with this method, including the destruction of all marine life through the de-oxygenation of areas of the ocean. Ocean acidification, warmer oceans, and disrupted current flows are also possible consequences. It is, however, possible for this process to occur somewhat naturally – that would involve returning sea life to pre-industrial levels (sustainable fisheries, elimination of ocean pollution, reduction of ocean acidification, and more).

The arguments

The arguments for Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), Direct Air Capture (DAC), and carbon sequestration through land or sea are very similar to the arguments in the case of solar radiation. We need more time to be able to decarbonise our economies; we have the technology available, so we should pour money into researching ways to make it commercially viable; and the fact that we should be fighting climate change “by any means necessary.” Geo-engineering projects allow Western societies to keep the status-quo lifestyle intact, and not make major changes to their dominant way of life and values. By allowing us to overshoot the target of 1.5 degrees, it permits emissions to continue for longer than they would otherwise be able. This current generation in power will not have to deal with the reality of climate change.

Capturing carbon from the air and from chimneys is seen as a much less risky way of geo-engineering than solar radiation and protection. It doesn’t involve disturbing ecosystems and climate patterns in quite the same way as injecting aerosols into the stratosphere. There is no risk of termination shock – any and all carbon captured and stored is a net benefit to the planet and humanity, and any that remains will be the cause of global warming – which we are currently facing. No added consequences will be felt.

The problem with all these technologies is that they require large amounts of energy, materials such as rare earth metals, and water, to be able to run. Each CCS plant requires around 6km2 of land space, and 30km of air-sucking machinery. To remove 1 trillion tonnes of CO2 (we have emitted 1.3 trillion tonnes since industrial times) would require land twice the size of India, or the whole of the land mass of Australia. That means large amounts of land would need to be reconverted to carbon capture plants, throughout the world. Land that could be reforested, used for farming, or housing, would have large turbines installed to capture and collect the carbon. In terms of water use, to capture and store just the yearly emissions of the United States, 130 billion tonnes of water would be necessary, each year. Estimates for the costs of such endeavours could be up to $570 trillion USD this century.

The technology for carbon capture and storage is currently being used in large part by oil companies to increase the yields of their oil wells, by injecting carbon dioxide that they have captured from the air. CCS is a way to increase profitability from oil deposits where the oil is difficult to extract. It’s hard to see carbon capture and storage as something other than a profit-seeking initiative by the companies who engage in it. As will be discussed in more detail in the Carbon Markets section, the first company who can capture and store 1 tonne of carbon dioxide for less money than the price of one tonne of carbon on the carbon market, has themselves a way of making immense profits. Perhaps that is why it is often not governments investing in this technology, but private individuals such as Elon Musk and Bill Gates.

In the case of biofuels, and Biomass Energy Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), growing large plantations of monoculture forests requires a very large amount of land. Were this to be taken up large-scale, land would be required both for agriculture and food, and energy. A fire, storm or flood that wipes out food crops and monoculture biomass forests would deprive a community of both electricity and food. Plants and animals that previously lived in areas devoted to monoculture forests would lose their habitat, and would be threatened with extinction. Even “marginal land” is not completely devoid of life. Further, if biofuel becomes more profitable to grow than food, there is nothing to protect people from farmers who convert their agricultural farms into forests to earn more, resulting in potential food shortages.

For the methods that use living organisms to sequester carbon, such as radiata pine trees on land and kelp in the oceans, these methods are not without their risks. All trees require time to sequester carbon from the air into the soil: this is not a process that happens immediately. Further, native biodiverse long-growth forests are much better in the long run at sequestering carbon than monoculture pine forests. They also support other living beings in diverse ecosystems, in a permanent way. If the land where these trees are grown is subsequently tilled or ploughed, much of the sequestered carbon will be released back into the atmosphere. The other oceanic option, growing kelp, risks massive de-oxygenation of areas of the sea, where it becomes impossible for any other marine life to live.

Money, Carbon Markets, and Investors

Why are world governments not funding geo-engineering projects at the same scale as private wealthy individuals? Who are the proponents of geo-engineering, and why are they advocating for it? Where is the money flowing, and who stands to benefit from geo-engineering projects? An important part of ecological analysis is to consider flows of capital, both material capital and money. Let’s dig into these questions.

More power, more money

Bill Gates has put $8 million USD into solar radiation management and direct carbon capture technologies. Elon Musk has allocated $100 million USD to carbon capture technologies. The Chan-Zuckerberg Foundation has given $11 million USD to genetically modify plants to increase their photosynthesis capabilities. Meanwhile, the United States Government in 2019 authorised only $4 million to be spent in geo-engineering research. In 2021, a 300-page report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in the United States, “Reflecting Sunlight,” for the first time recommended a coordinated national research programme to explore geo-engineering possibilities. Governments and think tanks around the world seem to be showing little interest in geo-engineering. New Zealand’s Government seems scared of the very use of the word, associating anyone who talks about it with conspiracy theory. A look through the Official Information Act requests demonstrates this.

To think that people such as Gates and Musk are simply benevolent and compassionate human beings looking after the welfare of the rest of the planet would be quite naïve. Surely they cannot have realised the colossal destructive impact that their empires have had on this planet, and are now repenting by paying us back with the invention of technologies to save the world. If they really did recognise the threat, they certainly would not be taking private jets around the planet, and would probably have wound up their businesses with interests in fossil fuels (most of them).

More likely, therefore, is that they are proposing geo-engineering because it is a way for them to keep the capital – in the form of wealth and power – that they have accumulated through a capitalist economic structure. They have a direct interest in keeping this fossil-fuel dominated way of life alive: it brings them more money and means they are powerful people.

These elites will retain their power because geo-engineering enables them to mask the true effects of increased carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Without solar radiation reflecting light back, world temperatures will increase by more than 1.5 degrees in at most 20 years. With it, however, world temperatures can be kept at an acceptable level. “Climate change” can be averted, never mind the other consequences. Their dream of a techno-rational empire, where science and technology are able to solve all of the problems of humanity, is one step closer to proving itself as the only way forward. Such an empire, of course, will not be controlled by world governments or organisations, like the United Nations; rather, it will be owned and run by private enterprise: the enterprises of Musk and Gates.

How will these wealthy individuals make money through geo-engineering the planet? The answer lies in the global carbon markets. In New Zealand, we have set up an emissions trading scheme (ETS) which puts a price on each tonne of carbon emitted. Companies can purchase the right to emit carbon into the atmosphere, and land owners or carbon extraction companies can sell credits to these companies, because they are storing carbon in the ground.

The first company or person who can store carbon for less money than it costs to emit one tonne of carbon enters into a very beneficial position: they can make others pay, through the carbon market, for them to store carbon in the ground, and make a profit.

For example, if it costs a company $100 to store 1 tonne of carbon in the ground, and the price of carbon on the carbon market is $200, for every tonne of carbon they store using their technology, they make 100%, or $100. A company with one plant that stores 8 million tonnes a year would, in this model, make $800 million a year.

The whole idea behind the carbon market is that the price of carbon will increase, so that net emissions will decrease. There is no future projection, in the long run, in which the price of carbon decreases, because that would mean more carbon emitted into the atmosphere, which is what the scheme is trying to regulate. It’s like investing in something with guaranteed returns.

Example: Make Sunsets

Make Sunsets, a start-up in the United States, is selling “cooling credits” at $17 USD each. These aren’t just for companies, but also individuals who want to invest in geo-engineering. Apparently, one cooling credit equals 1 gram of sulphur dioxide released, which will offset the warming effect of 1 ton of carbon dioxide for one year. This incredibly easy maths seems too easy to be true, and may in fact just be clever marketing more than accurate science. What’s more, individuals like you and me could offset our 15 tonne-per-year average emissions by paying $255 a year. Set and forget, monthly subscriptions are possible: the site looks just like any other online site where you could buy a coffee machine or a pair of shoes. We could just pay the money and wash all our sins away, and forget about any responsibility we have towards ecological destruction.

Their website’s FAQ has the following question: “I would like you to stop doing this.”

Their (quite arrogant) response is: “And we would like an equitable future with breathable air and no wet bulb events for generations to come. Convince us there’s a more feasible way to buy us the time to get there and we’ll stop. We’ll happily debate anyone on this, just confirm an audience of at least 200 people and we’ll find the time to try and convince you. 😉” As of May 2023, they have completed 20 flights for 96 customers. If they had $50 billion USD a year, they could offset the effects of all man-made emissions. They want more time for other people to do the work of decarbonisation, and because their actions are not regulated, they can deploy sulphur into the air, and make money from doing so. When the cooling credits were launched, they were $10 each in 2022. As time goes on, their cooling credits increase in price (now at $17), whilst the cost for deployment decreases as more people buy credits. Costs decrease, price increases, and the company makes a lot of money.

What they do not do, however, is take any responsibility for the consequences of their projects. They do not plan to donate any money to people affected by the deployment of sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere. Such a thing is too hard to prove, and no research could be conducted (and likely wouldn’t be financed in the first place): was it global warming’s fault or Make Sunset’s fault? All responsibility lies outside the company, and externalities are recognised but financially and legally ignored.

Make Sunsets is just one part of a host of companies and individuals financing carbon removal and solar radiation projects. A similar bet is being placed by Drax in the UK: burning wood chips is carbon neutral. If they can store the carbon actually released from burning the chips, then they have a net carbon-negative business. As well as selling energy, they make money through selling carbon offsets on the carbon market. The more trees they burn, the more they can sell on the carbon market.

The perpetrators of the problem are the ones that stand to benefit the most from geo-engineering projects. These companies are using investment money and promising returns on investment just like any other investment in Apple or Microsoft or SpaceX. The global carbon capture and storage market could reach $4 trillion USD by 2050, according to estimations by Exxon Mobil, a petroleum company.

In the end, investing in carbon capture technology is an investment in one’s own wealth, not in the future of the planet. Such an beneficial outcome for the planet is not even guaranteed, and comes with incredible risks: none of which will be paid for or recognised by the investors, who will have made their financial returns, and moved on to financing space villages, after destroying the climate system on planet Earth.

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. (2022) Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future. Crown Publishing.

Kolbert looks at the ways that human civilisation manages the environment, and the future of this management through geo-engineering. - Morton, Oliver. (2017) The Planet Remade: How Geoengineering Could Change the World. Princeton University Press.

An account of the reasons for geoengineering to take place, and the necessity to continue researching this. The book explores the history, politics, and science of geoengineering. - Malm, Andreas. (2022) The Future Is the Termination Shock: On the Antinomies and Psychopathologies of Geoengineering. Part One and Part Two. In Historical Materialism 30.4, 3–53.

Malm discusses the rational-optimist viewpoint towards the world in this article series. He strongly criticises geoengineering movements from all sides. - Science for the People. (2018). Summer Special Issue: Geoengineering.

https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/geoengineering-special-issue/

Science for the People break down all the viewpoints on geo-engineering in the United States context, with a variety of articles by different contributors on the topic. - New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2018) Low Emissions Economy.

The Productivity Commission discuss the ways in which New Zealand can transition to a low emissions economy. Discussed here are natural means of geo-engineering, namely, reforestation and carbon capture through tree planting and carbon credits (ETS). - Official Information Act requests on geoengineering in New Zealand, on FYI.org (here, question by Chris McCashin), shows the extent to which the Government deny any knowledge of or involvement with geoengineering. Also, in the comments on this page, you can see how a reasonable request is taken up by those supporting conspiracy and misinformation, who demand the Government be held to account for inaccurate responses.

It took more than 60 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

The corporate strategies to avoid change: an activist’s guide

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 13/07/2023

- No Comments

- Ideas, Politics

share

How do businesses and government deal with protests and demands for change? What is their strategy, and how do they go about maintaining their power and their position, throughout and despite the protests? And what about dialogue: how does that work, do meetings between activists and perpetrators often lead to change?

There are examples where activism has led to meaningful, systemic and long-lasting change. These examples, however, are few and far between. Western societies have known about the climate crisis at a societal level for at least 50 years, and in some cases longer. Environmental damage and conservation movements have existed for many hundreds of years. Yet, the same companies continue to destroy the environment, and governments around the world have proven themselves to be inadequate and insufficient for confronting the systemic problems leading to global ecosystem collapse. Dialogues at 27 yearly Conference of the Parties (COPs) so far, have led to zero reductions in net global carbon dioxide emissions.

So, how do companies deal with activists to keep doing the same thing? How do they neutralise the threats posed to their interests: making profit, assuring production of goods and services, and maintaining their power within the current economic and social system? This article explores the strategies and classifications used by companies, and increasingly by Governments worldwide to reduce threats posed by activists with valid claims for social and environmental justice.

The types of activists and how to deal with them

Ronald Duchin was a founding member of MBD, a company hired by the agriculture industry, the tobacco industry, the chemical industry, and many other non-declared clients, due to the secretive nature of the company. “Get Government Off Our Back” and “Regulatory Revolt Month” are some of the major campaigns brought about by the group in the US, always in favour of free and unbridled enterprise, and with the aim of shutting down all social and environmental activist movements.

In 1991, he gave a speech to the National Cattleman’s Association in the United States, entitled, “Take An Activist Apart and What Do You Have?”. In this speech, he described four groups of activists, and the characteristics of each group. This was the basis for the strategic work that MBD did with large companies to neutralise the threats posed by activist groups “who want to change the way your industry does business – either for good or bad reasons.” These four groups are the radicals, the opportunists, the idealists and the realists.

1. The Radicals

Those who “want to change the system,” and “can be extremist or violent.” These people are involved in specific causes because of underlying socio-economic or political motives, hate business and enterprise, and seek larger systemic transformation than the particular struggle they are fighting. With them, there is nothing to be done, according to Duchin. They must be isolated from the rest of the group so they lose their credibility.

2. The Opportunists

Those who are looking for “visibility, power, followers, and perhaps even employment.” They move from cause to cause, and are quick to change position or move to the forefront of a potential change in the following. If the society changes its opinion, they will change their stance to return to the front of the pack. They seek personal gain, and look for issues with the greatest potential for themselves. With these people, you must give them the impression of a partial gain or win. They are not interested in reality, but in their following, so if “the opportunist is provided the chance to be a participant in that final determination of policy, he/she has his/her victory, and he/she is satisfied.”

3. The Idealists

These are the moral and principled people, attracted to causes because they care about the outcomes for people and the planet. They are “usually altruistic, emotionally involved, naïve, and generally unaware of the unforeseen consequences.” They “want a perfect world and find it easy to brand any product or practice which can be shown to mar that perfection as evil.” They are credible and believed in the media and by politicians, because of their altruism and values. However, this makes them hard to deal with. “Idealists must be cultivated and one should respect their decision. […] They must be educated.” For Duchin, this means showing them that their opposition to a cause will cause harm to others and is not ethically sustainable in the long term. Once an idealist has realised the consequences of their position, they will be converted to a realist.

4. The Realists

The group of people to which companies should interact with the highest priority. They are “pragmatic, not interested in radical change, can live with trade-offs, and understand the consequences.” To respond to their demands, business must “meet with them, listen to their concerns, and be open that the industry’s agreed-upon solution may not be the best.” The solution agreed upon by the realists is often the one that is adopted by all members, if business is part of the decision-making process. If industry is not part of this process, then the radicals and idealists can gain more strength.

The main strategy is to listen to the realists, educate the idealists to convert them to realists, and ignore the radicals and opportunists at the beginning. These groups can be converted to believe in the position of enterprise and industry, with small adjustments to suit the demands of the realists. The radicals only have power when they are supported by the other groups: when they are alone, they lose their public credibility, so they must be isolated. The opportunists can be invited to join in the final policy resolution, as long as they have a moment to be in the spotlight. The issue will be resolved with the least fuss and the least change for the industry involved.

We see this strategy deployed all the time in relation to concerns regarding the environment and social justice. Protests occur, and the organisation in question will call for the protests to stop (isolate the radicals), put out their own statement with strong ethical language (educate the idealists), and then invite the realists of the group to a meeting to discuss their concerns (convert the realists). At the end, the opportunists get a photo with the high officials involved (swallow the opportunists), and the issue goes away, with very little change.

This was the strategy with the Save Passenger Rail protesters in New Zealand recently, too, in regard to the Government’s lack of climate action. Their actions were quickly denounced in the media as being a public nuisance, dangerous, and examples were found of people in their cars who missed appointments or were otherwise inconvenienced by the movements. The radicals were isolated from public opinion, so they lost their credibility for their cause. Showing that hard-working kiwis “just trying to get to work to feed their kids” were disrupted by the action played on the empathetic nature of the idealists. Meetings were had with the realists; the opportunists had a photo…

But, think of the disruption climate change will cause. Cyclone Gabrielle was disruptive. People on the streets for a few hours is nothing compared with the disruption climate change is causing, and will continue to cause, without serious measures taken by Governments and businesses worldwide. The counter-strategy was so effective that the protesters never really got to express their views to the public and explain the situation. Neutralised and the conflict brought indoors, to private meetings, the whole issue went away very quickly. The second time the protesters tried their action, the Government refused to meet with them again: “you’ve been unfaithful,” they said. “You’re disrupting our lives and our cities.” Instant de-legitimising and loss of credibility for the protesters. The realists were portrayed as no longer being realistic, but being radicals: isolating them all from the larger society once again neutralised the threat.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Dialogue as a means to inaction

At the beginning of the 1980’s in the United States, the calls from campaigners and social and environmental activists to regulate business action and for companies to adopt responsible business practice became louder and louder. To counteract these calls, industries in the US needed a new way of dealing with this, to protect their interests, guard against offensive government regulation, and neutralise the criticisms coming from various corners of the society.

As a result, companies joined in on the “ethical communication” bandwagon that was beginning to take hold at the time. Instead of fighting against ethical communication and openly promoting their profit-based interests, large companies realised they could be the champions of ethical communication. They could see their critics not as adversaries, but as partners, who needed to be brought to the table to bring about resolution to the problems they pointed out. Instead of fighting opposition, they could just swallow them up.

What this actually meant was that dialogues needed to be had, so that the companies could convince the critics that the position of business and industry was just, fair, socially motivated, and had everyone’s best interests at heart. They knew that they had to identify the realists amongst the critics, and talk with them to bring about solutions. Jean-Claude Buffle writes, in Dossier N… Comme Nestlé, “for them (the business), dialogue was not a way to open oneself up to the other, it was a strategy, another method to wage their war.” The goal of these discussions was not to exchange or negotiate, but to “convince people of their (business) point of view and motivate them to act for the company’s interests.”

In his book detailing the genealogy of authoritarian liberalism, Grégoire Chamayou notes six different virtues of dialogue as a strategy to maintain and guard power (p. 129-130). These are:

- Intelligence-gathering: having a dialogue with opposants means that companies can figure out potential problems before they reach the public arena and cause harm to the company’s image in the public eye. Companies can understand how the campaigners think, what’s on their minds, and what their future projects might be.