author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 26/02/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

A delicious pickled cauliflower to put on rice, in salads, or as a side to almost any meal!

Ingredients

1/2 head of cauliflower

1 cup apple cider vinegar

1.5 cups water

2 tsp salt

1 lemon

1/2 tsp peppercorns

Method

- Cut up the cauliflower into small pieces, trying to keep the florets together so you have pieces that are easy to take out when it’s finished. Slice up the garlic, and cut slices of lemon rind off the lemon with a sharp knife. Slice up the remaining lemon into thin slices.

- In a medium-sized pan, put the water, vinegar and salt together and bring to the boil.

- Add the cauliflower florets and leave to boil for 5 minutes.

- Take off the heat, and in a large glass jar, add some slices of lemon and some pieces of lemon zest. Top this with some pieces of cauliflower from the pot.

- Continue making layers in this way, and about halfway, add in some of the garlic and peppercorns. Finish with a layer of lemon slices on the top.

- Fill up the jar to the top with the liquid left over in the pan. Use enough to cover the cauliflower completely.

- Let it cool down at room temperature, then put the lid on and put it in the fridge. The pickle will be ready to eat in around 48 hours, but it gets better and more lemony with time!!

Our food section provides ideas and inspiration for great, fresh food. Our recipes will always be open and free for everyone to use, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Vegan ‘nduja paste

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 04/02/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

Originally a spicy Italian salami paste used in sauces, dressings, salads, pasta, and more, this umami-filled vegetarian/vegan version is absolutely brilliant with watermelon and feta cheese as a salad, or in a tomato sauce with fresh pasta to add an extra kick of spice and flavour.

Ingredients

45 grams of sundried tomatoes (not in oil)

1 clove of garlic

1 tsp smoked paprika

2 heaped tsp miso paste

1 tsp fennel seeds

1/2 hungarian wax chilli, or two birdseye chillis, or chilli to taste

1 tbsp red wine vinegar

1 tbsp neutral oil like sunflower oil

Method

- Soak the dried sundried tomatoes in 1/4 cup boiling hot water for about 30 minutes.

- Cut up the chilli and garlic into fine slices, and then put into a blender or small food processor, along with the other ingredients including the tomatoes and the water.

- Mix together until you get a smooth paste.

- Store in the fridge until you need to use it!

Our food section provides ideas and inspiration for great, fresh food. Our recipes will always be open and free for everyone to use, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Pad kee mao

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 30/01/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

A delicious Thai-inspired dish that has been made vegan by making your own oyster sauce and fish sauce, and using tofu as your protein! The fresh basil takes it to another level, a great crowd-pleaser!

Ingredients

Serves 4

Vegan oyster sauce:

10 dried shiitake mushrooms, soaked in 2 cups water

1 tbsp finely chopped ginger

1 tbsp oil

1/2 cup coconut aminos

8 pitted dates

Vegan fish sauce:

1 cup water

3 tbsp dulse (seaweed pieces)

2 tsp salt

1/4 cup dried shiitake mushrooms

1 tsp miso

1 tbsp tamari (or soy sauce)

Pad kee mao sauce:

4 tbsp vegan oyster sauce

1/3 cup soy sauce

2 tsp vegan fish sauce

2 tsp brown sugar

2 tbsp water

1 tsp chilli sauce/fresh chilli

Noodles:

200g wide rice noodles

2 tbsp oil

2 shallots, or one onion

1 carrot, thinly sliced

200g firm tofu

4 cloves of garlic, chopped

1 courgette, sliced

1 small capsicum, sliced

2 spring onions, thinly sliced

1 tomato, chopped

1 cup of Thai basil, or regular basil, chopped

Method

For the vegan oyster sauce:

- Soak the shiitake mushrooms in warm water for around 4 hours, until soft. Take them out of the bowl, squeeze out the water, and then thinly slice them. Strain the remaining water to remove any dirt.

- In a hot pan, heat up the oil. Then add the sliced mushrooms, ginger, and a pinch of salt. Sautée for about 4 minutes.

- Add a tablespoon of the coconut aminos to the mushrooms in the pan. Take off the heat after one minute.

- Put the mushrooms and ginger, the soaking water, the dates, and the rest of the coconut aminos in a blender and mix for a minute or so until you end up with a smooth liquid. Set aside to use later.

For the vegan fish sauce:

- In a saucepan, add the water, dried mushrooms, salt, and the dulse. Heat until boiling and leave to cook for 15 minutes on a low heat.

- Remove from the heat, and let it cool slightly. Pour the mixture through a sieve, and squeeze out the juice from the mushrooms and the seaweed.

- To the bowl with the liquid, add in the miso paste and the tamari. Mix these in to the sauce. Set aside to use later.

The noodles

- Prepare all the vegetables by slicing everything up and putting them in piles on your chopping board to use. The secret to this is being able to cook everything quickly in a hot wok or frying pan.

- Mix the ingredients for the sauce in a separate bowl and set aside.

- Heat up a pot of boiling water for the noodles, and when you are ready to cook the vegetables, put the noodles in the boiling water.

- In a wok, add one tablespoon of oil and heat until hot. Add the shallots/onions and the carrots, and cook for two minutes. Then add some more oil, and add the tofu. Cook until the tofu is golden brown.

- Add the vegetables and the garlic and cook for another two minutes.

- Strain the noodles when they are cooked, and add them to the frying pan on top of the noodles. Pour the sauce on top, and then mix the sauce into the vegetables and noodles. Stir until well mixed through.

- Take off the heat, and add the chopped basil, then serve!

Our food section provides ideas and inspiration for great, fresh food. Our recipes will always be open and free for everyone to use, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Spelt pasta with green beans, red onion and chickpeas

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 25/01/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

A delicious way to include home-grown green beans if you’ve got too many, and a perfect pasta salad for a warm lunchtime or dinner meal together.

Ingredients

Serves 4-6

Spelt pasta:

3 cups of white spelt flour

1/4 cup pumpkin seed flour (can omit if you don’t have it)

1 tbsp chia seed flour

cold water

Sauce:

1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil

4 cloves of garlic, sliced

1/2 large red onion

3/4 tin chickpeas, drained and washed

handful of fresh basil leaves

handful of coriander leaves

two handfuls of green beans

2 tbsp lime juice (add more if you like this lime flavour!)

salt and pepper to taste

optional: feta cheese or parmesan, cherry tomatoes on top

Method

For the pasta:

- Mix together the spelt flour and pumpkin seed flour in a large bowl.

- Create a ‘chia egg’ by mixing the chia seed flour with about 1/4 cup of water until you get a thick paste. Add this to the flours.

- Mix in the chia liquid with your hands into the flour. Start by adding flour on top of the chia, and mix it in, slowly adding more flour from around the sides of the bowl.

- Add more water once the chia egg is well mixed in, until you get a dry dough texture.

- Knead the dough vigorously for about 5 minutes until it springs back when pushed with your finger.

- Let the dough rest, covered, for 30 minutes.

- Uncover the dough, and break off about 1/6 of it. If you have a pasta machine, use this to roll out and cut the piece of dough. Otherwise, using a rolling pin on a floured surface, roll out the pasta sheet to about 3mm thick, and then fold it in half and roll it out some more. Continue this method of folding in half four times.

- Roll out the pasta until it is about 1mm thick. It should hold its structure well, but not be so thin that it tears. Generally a bit see-through is perfect.

- Cut the piece into long strips, like tagliatelle, or wider strips, if you want parpadelle pasta. Repeat for the rest of the dough.

For the sauce:

- If you have the oven on already, put the chickpeas in a roasting tin with some olive oil, salt, and a few of the herbs. Bake until crisp. Otherwise, in a saucepan heat up some of the olive oil and add the chickpeas, salt, and herbs. Cook them until they start to go golden brown and begin to crisp up.

- Meanwhile, prepare the beans by cutting them into 3cm pieces. Using a steamer or just some water in a pan and a sieve on top, steam the beans for about 5 minutes or until tender. Don’t overcook them – some crunch is good!

- Transfer the chickpeas to a bowl. In the same pan, add the remaining olive oil, the sliced garlic, and some torn up basil leaves. Fry this on a low heat until the garlic and the basil go crisp. Add the lime juice and stir.

- Chop up the remaining basil and coriander into rough pieces. Also finely slice the red onion and add these to a bowl.

Finishing

- Heat up a large pot of water until boiling. Once it is on a rolling boil, add a pinch of salt to the water. Then add the pasta, and cook for about 3 minutes, or until ‘al dente’.

- Strain the pasta, and add a glug of olive oil and stir through to stop the pasta from sticking. In a large bowl, add the pasta, the beans, the herbs, the red onion, and then pour over the sauce. Add some salt and pepper to taste, and then mix your pasta salad together carefully to coat the pasta in the sauce.

- Plate up with the chickpeas on top, adding cheese and tomatoes if you like!

Our food section provides ideas and inspiration for great, fresh food. Our recipes will always be open and free for everyone to use, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Why eating well is ecological

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 25/01/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

The Plurality.eco food section is all about eating in ways that are better for your own health, and for planet Earth. But just how is eating well going to be better for you? And how can a way of eating be considered ‘ecological’, meaning that it also makes a political statement at the same time?

Let’s briefly think about what we mean by ‘eating well.’ We might say that everyone’s ‘eating well’ is different, and that’s true. Here, eating well means buying fresh, unprocessed and low-packaged food that is cooked and prepared at home. This is what many people call a ‘whole foods plant-based diet’ which is very close to the Mediterranean diet. Eating well means reducing meat and dairy consumption because you are aware of both the environmental and health impacts of eating these foods. It means being aware and conscious of what you are eating, and what effect this will have on your health, and on the health of the ecosystems in which this food is produced.

There are many ways in which eating well is ecological. Let’s go through them one by one, exploring both the theoretical foundations, as well as the scientific evidence for these reasons.

Image: Jacopo Maia on Unsplash

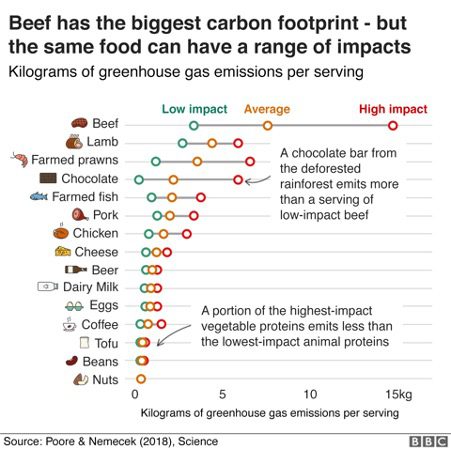

1. Eating a vegetarian diet lowers your carbon emissions, and a vegan diet lowers them even more. Seasonal and local is better than out of season products from everywhere.

One of the pledges that governments across the world have made is to lower their emissions of greenhouse gases. This is so that the global warming which is occurring at the moment will slow down, because fewer gases like carbon dioxide in the air mean less warming on a global level.

This engagement is something that needs to be taken up by individuals, companies, and governments. Each has their part to play in the reduction of emissions. One of the ways that people can reduce their own carbon emissions, or ‘carbon footprint’ is through eating less meat and dairy, especially from animals like cows, which release large amounts of methane into the atmosphere. In the short term, methane is about 80-100 times more powerful at warming the planet than carbon dioxide.

By becoming vegetarian, you can reduce your carbon footprint by around 1.4 tonnes per year. Eating only a quarter of your yearly meat consumption will reduce your footprint by one tonne. Given that the average footprint for a New Zealander is 15 tonnes per year, this is quite a large reduction! Especially as it is one that we can choose to make immediately, and it will have a large impact if many of us decide to reduce or eliminate our meat consumption.

Looking at the graphic from the BBC below, you can see that plant-based proteins have lower emissions than many other foods.

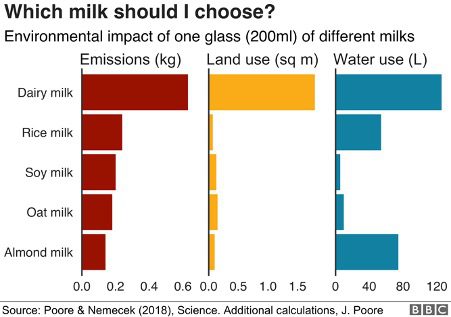

You might be trying to reduce your carbon footprint, but as we discuss here, carbon emissions are only one part of the ecological crisis. There are also other concerns – like the amount of fresh water we use to grow certain crops or raise cattle for food. When it comes to water usage, vegetables seem to require the least amount of water to produce, then fruits, then animal products, which require very large amounts of water. This article by TheDataAnalyzer is a great explanation of the water resources required for different food products. You can also see and download the whole dataset, to know just how much water is used by things such as cacao beans, nuts, grapes, beer, and more.

We should watch out here, because we might think that almond milk is a good alternative to dairy milk – which, overall, it is. However, the amount of water required to produce almonds for this purpose is much more than that required to make oat, soy, or rice milks.

Becoming a vegetarian, or even a vegan, is one good way to reduce your carbon emissions, and the fresh water usage required to produce your food. Eating vegetarian requires much fewer resources, in terms of both land and water, and will emit fewer greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

One criticism of this choice is that, with increasing requirements for vegetarian protein sources, like soya, almonds, etc., it is becoming necessary for farmers to intensify their production of these crops. This is meaning more almond trees per square kilometre, greater pesticide use, and mechanised farming systems in order to keep up with demand. Monocultures like this end up having negative effects on the soil quality, plants begin to produce their own toxins to fight against the use of the pesticides, and there is a greater chance of disease and pest infestation in the farm. The European Union explain this in more detail here.

Likewise, organic farming is on average around 20% less efficient than more conventional intensive farming methods. This means using more land, which would not be so much of a problem if we weren’t using large amounts of land for raising animals to eat them; however in the current situation more organic farming would mean using more resources and more land for farming.

Overall, the benefits in terms of lower resource use and lower greenhouse gas emissions means that becoming vegetarian or vegan is a great way to reduce your personal impact on the environment. The more people who eat in this way, the greater the efficiencies in the production of these foods can become. Fewer animals will need to be raised to contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, and land can be used and reconverted into growing crops for human consumption.

2. Taking back agency and having greater self-determination

The second way in which eating well is an ecological act is more political than the first. Being ecological means realising that the interests of large companies have come to dominate many areas of our lives, in ways which do not always have the interests of human health at the forefront.

One such example is the use of bisphenol-A (BPA) in plastic products. BPA was used in plastics coming into contact with food, and is still used in many products like cosmetics, eftpos receipts, phone cases, and more. BPA is used by companies to make a shatter-resistant, lightweight and clear plastic. However, peer-reviewed research has found that BPA is what’s known as an ‘endocrine disruptor.’ This means that it stops the body from functioning properly, causing diseases such as breast, ovary, colon, and prostate cancer. Even touching products with BPA in them causes the compound to enter the body through the skin. BPA is used because of its practical and financial benefits. As these plastics became more widespread, no interest was taken by its producers in its effects on human health.

Eating well therefore means that you are active and aware of what you eat, what you put into your body. When you eat well, you don’t buy products with chemical preservatives and flavour enhancers in them, because you don’t need these to make a good meal, and don’t want them in your food. You choose not to buy products and containers with BPA in them, for example. You’re therefore asserting your agency, your ability to choose, against a system which has other interests at its centre. You are declaring that your own interest in your health is more important to you than participating in a food system where profit drives production choices.

It is precisely this money and profit-driven economic system which is responsible for the ecological crisis. By not including the ecological impacts of production in their business analyses, companies destroy ecosystems and extract resources at rates much faster than these resources can regenerate themselves. They then sell us the idea, through advertising, that we have to buy their new product, which is better than the one we’ve got, and we generate more and more waste which takes thousands of years to decompose.

The ability to say no, and to make your own food choices, is a way of fighting back against a production system causing the ecological crisis. The more people who decide to make conscious food choices – whether that be vegetarian/vegan or not – the less this power this system has in our overall decision making. When no-one buys products with toxic plastics, these toxic plastics will no longer be used, even if it is only because the companies do not want to lose their customers.

And there is evidence that companies are listening to this kind of consumer behaviour. For example, the number of products that are certified organic has increased dramatically over the past decade. In New Zealand there are 11 different ways in which products can be registered as organic, according to the Ministry for Primary Industries. The organic industry in New Zealand grew by 4.5% in 2021, and is expected to continue this growth rate for the next few years. As we mentioned above, organic doesn’t always mean a smaller environmental footprint, because of the extra resources required to grow organic food. It does however mean better health outcomes, for humans, and for the soil and ecosystems in which the food is grown.

3. Better health outcomes, both physical and mental

Eating well – that is, eating unprocessed, fresh whole grains, fruit and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and legumes – is going to lead to you living a healthier and longer life.

One of New Zealand’s leading nutritional and psychological scientists, Julia Rucklidge, at the University of Canterbury, has written a lot about the impact of diet on mental health.

She concludes that a whole-foods plant-based diet, often called a Mediterranean diet, shows remarkable results in improving mental health across different populations. Those on a poor-quality diet are 60% more likely to suffer from mental health conditions like anxiety and depression. Rucklidge encourages those who do suffer from depression to adopt a whole foods plant-based diet, which in the SMILES trial, showed that diet intervention was more effective at treating depression than social interventions. You can take Rucklidge’s online course in Mental Health and Nutrition to learn more about these links here.

On the physical health side, eating a whole-foods plant-based diet of unprocessed fresh foods has been shown in numerous cases to lead to reductions in the risk of what we call “non-communicable diseases”, which are the most prevalent causes of bad health and death in Western societies today. These include diabetes, cancer, dementia and Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular disease, and more.

One very accessible book discussing the research done on the relationship between diet and health outcomes is Simon Hill’s “The Proof is in the Plants.” Discussing recent studies as well as looking into the claims made by industries, Simon Hill does a great job of sorting fact from fiction when it comes to health. Many industries will publish studies that provide confusing results, or that support the industry, and to do this they design their research study in order to get the results they want. One example could be to release a study which says that “eating dairy is good for your health.” This could be a study which shows a group of people who eat lots of red meat and processed food, and another group who eat all that, plus dairy, and on certain measures have better health outcomes. This doesn’t mean, however, that people on whole-food plant-based diets won’t have even better health outcomes, without dairy.

Some of the conclusions that Hill comes to in his book are quite important. There is a big misconception that people on vegetarian and vegan diets don’t or can’t get enough protein in their diets. This is simply not true: he writes “if you are eating a whole-foods plant-based diet with just moderate diversity, your body will get all the EAA (essential amino acid) protein building blocks it needs.” This is based on a review of many different large-scale studies.

Hill also writes that “it’s estimated that dietary choices may be linked to as many as 50–75% of all deaths by breast, prostate, colorectal, endometrial, pancreatic and gallbladder cancers.” In Australia, 95% of people fail to meet the daily recommended fruit and vegetable intake guidelines. It’s no surprise that this is the case.

Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) has recognised the role that processed meats play in causing cancer. Meats such as bacon, salami, sausages, ham, etc. were listed as Group 1 carcinogens in 2015, along with tobacco and asbestos. These foods are just as potent and dangerous, and likely to cause cancer, as smoking cigarettes. They also happen to be highly transformed foods, which go through factories and production processes to fill them with chemicals and additives. The WHO also classified unprocessed red meats like beef, lamb, pork, horse, goat… as Group 2A carcinogens, meaning that they are “probably carcinogenic (cancer-causing) to humans.”

So, eating red meat has a higher carbon footprint, requires more land and water to produce, is probably causing cancer in human beings… The reasons to eat a whole-foods plant-based diet are just increasing.

Eating well is therefore ecological because you are taking care of your health. In personal terms, this means living happier, for longer, with a much lower risk for disease. In political terms, this means less money needing to be spent on preventable diseases in the hospitals and care centres – money which can then go towards other ecological political measures.

4. Better state of the planet and local ecosystems

Intensive farming of animals for human consumption requires a lot of resources, as we have seen. It also emits a lot of greenhouse gases – more than any other food product. But we must remember that these farms of dairy cows and sheep are not in isolated and unconnected silos. Rather, each farm sits on the Earth and its impacts influence the soil underneath the farm, as well as the surrounding areas, especially where water and air are concerned.

Farming animals in such large quantities in small areas produces enormous amounts of dust from feeding troughs, which ends up in the air that we and other forms of life breathe in. This dust contains biologically active organisms such as viruses, mould and fungi from the food and the animal faeces which is in the dust. Likewise, animal waste is collected in pools so that it can be treated before being used as fertiliser on crops such as vegetables, oats and barley. In these pools, the waste evaporates and releases toxic chemicals into the air. This has an effect on human health, as this New York Times article discusses.

Besides air pollution, there is also water pollution to consider. When all the toxic animal waste is spread onto the land in order to fertilise crops, it also ends up in the waterways and lakes, which then takes it to the sea. In the Gulf of Mexico there is what we call a ‘dead zone’ where all the plant and animal life has died. This is because of toxic runoff in the form of nitrogen from industrial farming practices, which travels by the Mississippi River to the sea. In this study, researchers looked at the impact of shifting away from crops destined for meat production, to growing other protein sources for human consumption in the Mississippi Basin. They found that doing so would reduce the size of the ‘dead zone’ to being almost non-existent.

By switching to a vegetarian or vegan diet (a whole foods plant-based diet), we are reducing the amount of land which is needed to grow crops for animal consumption, which in many cases is causing this toxic runoff into waterways. We are also reducing the greenhouse gas emissions, because there will be fewer cows, sheep, and other animals producing warming gases. We’re also improving air quality when animals are no longer factory-farmed to meet our needs.

There are many small-scale alternatives to industrial farming, which can improve the quality of local ecosystems, such as regenerative farming, permaculture, and biodynamic farming. The trouble is that in many cases, we are unable to know as consumers under what conditions our fruit and vegetables are grown. Thus, eating well potentially means improving the quality of soils and creating resilient farms, rather than environmental destruction. At this stage there is no good way of knowing for sure that what we are buying and eating was grown in this way.

When we farm in regenerative ways, or even simply in organic farming, we are using fewer pesticides on the foods, which in turn makes for a healthier ecosystem too. Pesticides are very often not specific – they kill everything that comes into contact with the spray. Using these sprays simply mean that the pests we are trying to kill develop resistance to them – therefore rendering the sprays less effective. When plants are planted with high levels of diversity, i.e. not all the same plant in one area, the plants will naturally be resistant to most pests, and will help each other out to keep the pests under control. Because our food system is more interested in efficiency and cost savings, we plant one single variety in large areas, and this natural pest resistance is lost.

Eating well is, once again, shown to be ecological – it means that ecosystems are given the chance to ‘breathe’ without toxic animal waste and parasites being loaded into them. Waterways can become cleaner, soils can regenerate, and the air becomes less polluted with harmful contaminants.

5. Food becomes important – and a moment of connection

Being ecological means recognising the importance of relationships. Ecology tells is that everything is interconnected, and that each thing is made up of connections, of relationships, between different things in its environment, and beyond.

Food is one way in which many of us connect. Eating together is a way of sharing a moment together, and focusing on developing our relationships with other people. We all eat the same food, we share the same meal, and at the same time share parts of ourselves as well.

When you are eating well, and intentionally, then you are choosing to value the meal times that you have. Instead of sitting in front of your television, mobile phone, or computer, you choose to sit with others, and share your eating moments with them. Food habits become ecological behaviours, ways of caring, ways of understanding relationships.

The sixth reason would be the classic vegan argument – ethics! But I think this argument is fairly well known by most people. It goes something like this: Eating living sentient beings is morally wrong because we are causing them suffering in order to feed ourselves. Ethical and value-based thinking is also ecological, but we must always make sure that we are not supposing ourselves to be moral judges of others and their behaviours. We are not here to blame or point out the faults of others. The ecological crisis will not be overcome by counting the number of supposedly ‘good acts’ each person does, and punishing those who have done fewer than others.

This kind of thinking does not empower people to take active steps to understand themselves and the crisis that we are in, and it further reinforces the idea that environmentalists (because many of them tend to be vegans) are just annoying people who think they are morally superior to others (which sometimes can be true, but not always!). More on that perception in another article, however!

As you can see, there are many reasons why eating well is ecological. You can lower your carbon footprint, improve your own health, improve the quality of the soil and water systems where food is grown, take back your own agency and decision-making power, and spend more time connecting with others. Food is important to us: each and every culture has its own unique food traditions, which we can continue to share with each other when we eat in intentional ways.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

Manifesto for good food

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 17/01/2023

- No Comments

- Food

share

A poem to express the importance of good, fresh food. The Plurality.eco food section is all about how fresh, healthy food can save both you and the planet.

Image: Jacopo Maia on Unsplash

Amongst all the plastic, the additives, the chemicals and the gunk,

there lies a very simple component that somewhere got sunk:

the vegetable itself, of course, or the fruit,

the bean, the grain, and the nut minus the suit.

These simple elements at the heart of our dishes

don’t need citric acid, flavours, colours and wishes,

they shouldn’t be found in packets and boxes

nor mushed up, nor hidden, nor covered in toxins.

These things are not food for they sure aren’t nutritious,

they’ll give you inflammation and disease

and surely aren’t that delicious.

Vegetables, dear friends, are the solution to your woes:

they taste great, they look nice,

and oh how they come alive

with oil and spice!

And beans, I tell you, are powerhouses of goodness,

there’s vitamins and minerals and protein in hummus –

just enough for each day of course,

and even for those who eat like a horse!

But wait you are saying,

you cannot be right:

I can’t cook vegetables

and I’m not prepared for the fight!

Then all you must do is get to know them:

what they love, what they hate,

who they envy, and their mates.

So cook, dear friends, and watch your palate come alive,

with colour and flavour and a wee little jive,

you might be disappointed with your first try,

but again and again and you’ll surely fly.

Just remember these rules and you’re sure to be right:

fresh and nothing less, that’s every night.

A grain, a vegetable, a bean and some leaves

add a few herbs and spices or even some cheese.

Try, test, experiment and explore,

the exciting world of food will only leave you wanting more!

Our food section provides ideas and inspiration for great, fresh food. Our recipes will always be open and free for everyone to use, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. By eating well, and in ways that have a better impact on the environment, we can begin to change the way the whole society produces food.

If you've learned something today, or feel inspired, please consider donating, to help us produce more great recipes and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.