author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 14/12/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology

share

A wrap-up of 2023’s major climate events.

Image: AI-created on perchance.org

Global trends

We had multiple days in 2023 where global temperatures were more than 2˚C greater than pre-industrial levels. The Paris Agreement states that governments should aim to keep global warming to a maximum of 1.5˚C, so this trend of increasing temperatures is alarming.

The estimation for this year’s average temperatures is around +1.40˚ – 1.46˚C above pre-industrial norms, +0.13˚C higher than the hottest year on record, 2016. This will make 2023 the hottest year since records began.

In terms of carbon dioxide, levels in the atmosphere are 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.

Scientists across the globe are alarmed at the rate of change in climatic conditions shown in 2023. They are concerned because 20 of the 35 different “vital signs” for the health of the planetary system are now at record extreme levels. Read the Plurality.eco article about this here.

Month by month

In February, Cyclone Gabrielle hit the upper North Island of New Zealand, causing severe damage to homes and agricultural land. It was declared the worst storm to hit New Zealand this century.

In March, Cyclone Freddy hit Madagascar, Mozambique and Malawi, causing severe damage, and affecting hundreds of thousands of people. Cyclone Freddy travelled 10,000km over 35 days, making it the longest, and also the most powerful storm ever recorded. Mozambique received the same amount of rain in one month that it would normally get in a year.

Long-term drought conditions continued to worsen in Central and South America, with rainfall 20-50% lower than normal in the first half of the year.

Record-breaking temperatures were recorded in Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria, with temperatures reaching 49-50˚C in July.

The deadliest wildfire in more than 100 years of US history occurred in Hawaii at the beginning of August. At least 99 people lost their lives, and whole towns were burned to the ground.

June-July-August 2023, the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere, were the hottest experienced on Earth for at least the past 120,000 years. The average global temperature was 16.77˚C.

In September, Cyclone Daniel caused extreme rainfall and flooding in Greece, Turkey, Libya and Bulgaria, with a heavy loss of lives in Libya in September.

October was the most humid month since weather records began. This is due to higher-than-normal global temperatures and the El Nino weather event.

The COP28 conference finished mid-December in the United Arab Emirates, where the major discussion was about the phase-out of fossil fuels. 2,500 fossil-fuel lobbyists attended the conference. The President of the Conference, the Sultan Al Jaber, declared that there was no scientific proof behind the phase-out of fossil fuels. The Conference is, despite this, one of the only places where each country can have its voice heard, including developing countries who often speak about climate justice.

The World Meteorological Association provided an overview of climate events in 2023 here.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

It’s easy to forget the climate events that have happened this year, especially when news cycles are so short, and new information and events are appearing each day. Taking the time to look at events such as climate change over the space of a year can help us to understand just how this phenomenon is affecting us, across the world. Climate change is not coming, it is most certainly already here. As the IPCC’s Sixth Synthesis Report pointed out, it’s what we do now that will determine how bad the effects will be in the coming years.

More on climate science...

To understand more about the climate crisis, and the larger ecological crisis, read our article What is the Ecological Crisis here.

To read about the climate science that we currently have, from the IPCC report earlier this year, read our summary article here.

To read about what we know about biodiversity and ecosystem services, check out our article on the IPBES report here.

You can also donate to Plurality.eco, to support articles like this breaking down climate science and bringing a balanced perspective to the climate debate.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

On social media

Need some help to get to the next stage of your ecological journey?

Copyright © Plurality.eco 2024

2023 Surprises Scientists at Pace and Scale of Climate Change

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 26/10/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology

share

Have we passed the point of no return with the climate and planetary systems? The warning signs are there.

Image: AI-created on perchance.org

Since 2019, a group of scientists have published a “State of the Climate” article which discusses some of the major climate events and climate-related research to date. The 2019 article declared a climate emergency, which has since been signed by 15,000 scientists worldwide. The 2023 article by Ripple et. al has just been published in BioScience here: The 2023 state of the climate report: Entering uncharted territory.

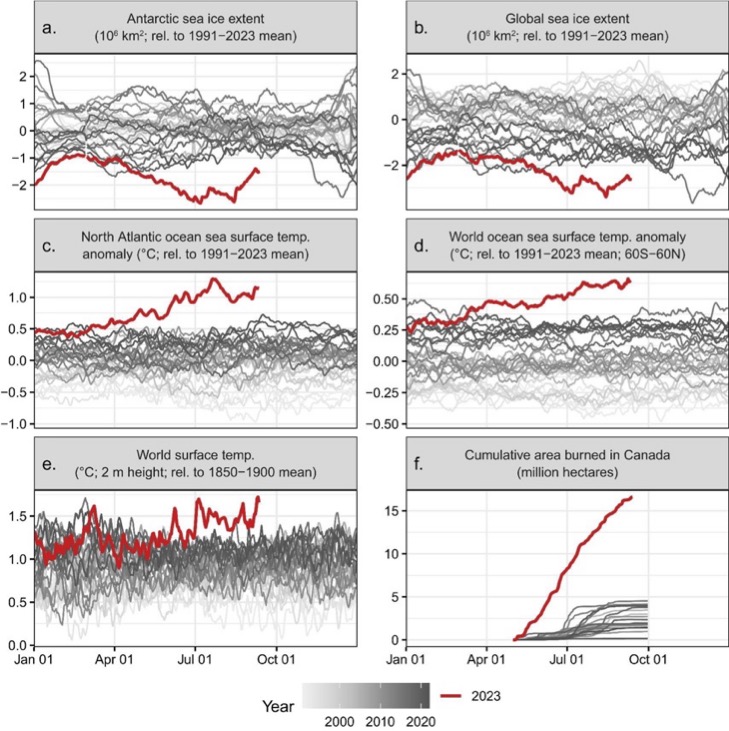

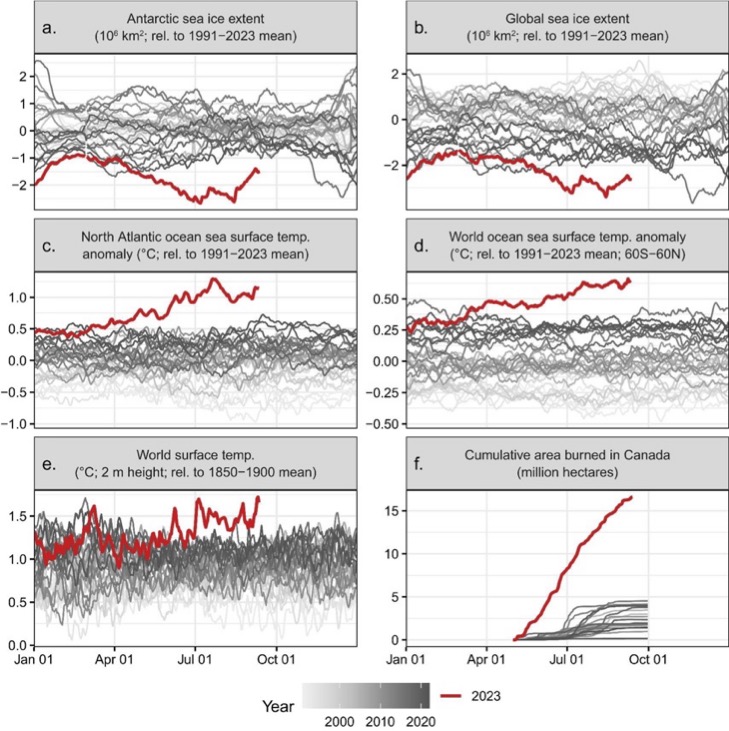

2023 has been particularly notable as a year of climate instability, major climate disasters, and records being broken by huge margins. Scientists are concerned because 20 of the 35 different “vital signs” for the health of the planetary system are now at record extreme levels.

The authors write, “The rapid pace of change has surprised scientists and caused concern about the dangers of extreme weather, risky climate feedback loops, and the approach of damaging tipping points sooner than expected.”

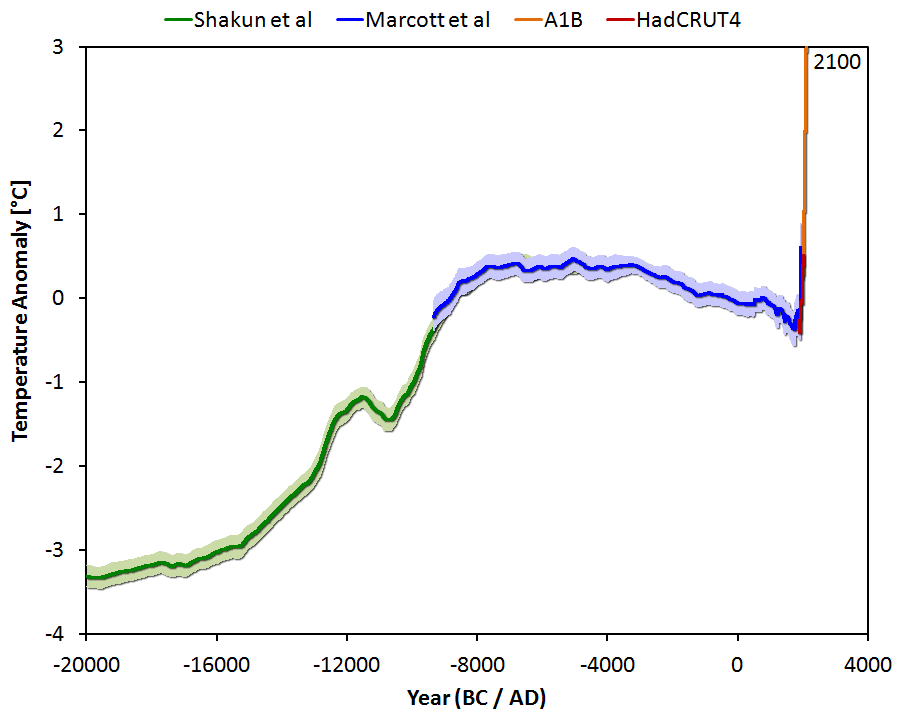

The authors, climate scientists, are surprised by the magnitude of the changes we are seeing: “Even more striking are the enormous margins by which 2023 conditions are exceeding past extremes.” As we see in the image, following the red line for 2023 shows huge differences compared to past norms on these six different metrics for climate change.

Why are scientists surprised?

Climate science has always been approximative – we make the best guesses we can about the possibility of extreme weather events in the years to come, but this is only based on the information we know about the climate. The existence of so-called ‘tipping points’ is not necessarily something that exists in nature, but rather a way for human beings to mark out the point at which a system which was previously quite stable, becomes very unstable. Just when and where these tipping points are, and what causes them to be reached, is still the topic of much scientific research.

Because we still know so little about the climate system, and the Earth’s other regulating systems, it’s difficult to know whether the predictions that have been made will be accurate in the future. It would seem that the rise in unpredictable climate events has occurred sooner than we thought – many climate scientists have predicted reaching or passing tipping points around 2030. However, we may have already gone too far, and already passed the point at which the planet can cope with our activities.

350 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is the goal we have for a safe and stable climate system. In 2023, we reached 420 parts per million, and this number is increasing year-on-year. Global emissions are not decreasing, which they must do in order for humanity to confront the climate crisis.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

The challenge for scientists

The article reads a little bit like something from the film Don’t Look Up, which explored the emotions scientists feel towards societies which don’t act in the face of a disaster. In the film, the group of scientists who discovered that a meteorite was going to destroy life on Earth attempted to warn people, but in the end, those in charge and some parts of the population chose not to listen to these warnings – and not to act in the face of them. In the face of this, the scientists became emotional – angry, sad – and therefore lost the objectivity that we like to think science has.

The series of State of the Climate articles are hotly debated amongst scientists for their lack of real rigour, and the inclusion of moral sentiments and the promotion of certain solutions. The group of scientists responsible for these articles have started talking about what we should and should not do, rather than just presenting what we know about the situation. Is this the role of the scientist?

For example, the report states “We also call to stabilize and gradually decrease the human population with gender justice through voluntary family planning and by supporting women’s and girls’ education and rights, which reduces fertility rates and raises the standard of living (Bongaarts and O’Neill 2018).”

Is the reduction of the human population through fertility control an acceptable conclusion for a scientist to make about climate change? And is an article on the state of the climate the right place for this kind of opinion?

It is difficult for scientists to balance the care they feel towards their lives, their loved ones, their countries, and planet Earth, with the requirement that we place on them to be objective and only present what we know as fact.

The report also relies a lot on media reports, and includes photographs of climate-related damage. We could also ask, is this kind of strategy, to elicit an emotional response in a scientific article, the right way to present information to other scientists and the public? Or does it, once again, cost us the objectivity that we require of the sciences?

Being a climate scientist and reporting on the state of the climate is tough. Especially when the facts paint a very distressing picture of the future of life on planet Earth. That is why it’s particularly important to act now. Every tenth of a degree of warming sets up a more hospitable future. You can act to reduce your emissions, talk to your local council or Member of Parliament about their plans to respond to climate change, and try to discuss climate change with your friends and family.

More on climate science...

To understand more about the climate crisis, and the larger ecological crisis, read our article What is the Ecological Crisis here.

To read about the climate science that we currently have, from the IPCC report earlier this year, read our summary article here.

To read about what we know about biodiversity and ecosystem services, check out our article on the IPBES report here.

You can also donate to Plurality.eco, to support articles like this breaking down climate science and bringing a balanced perspective to the climate debate.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

What is deep ecology?

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 30/05/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology, Politics

share

Perspectives in political ecology series

The aim of this series of articles is to delve into the different perspectives in political ecology. It is absolutely not the case that there is only one way to address climate change. There are, in fact, many! More technology, carbon removal, and business as usual is but one way of confronting the crisis, and this approach misses the mark in so many ways. Read on to discover what deep ecology is, who its founders were, and whether we see many deep ecology movements amongst climate activists today.

The basic definition

The term deep ecology was coined by Arne Naess in 1973, with his article, “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement. A summary.” Naess sought to point out the difference between certain ecological movements which viewed problems in silos, and believed that each could be treated with technical fixes and economic policies; and those which sought deeper systemic or structural change in spiritual and social systems.

Shallow ecology, therefore, is a particular approach to the ecological crisis which identifies particular problems, and proposes technological or instrumental solutions to these problems. For example, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is a problem, and we can solve this through carbon capture technologies which will be developed to take the carbon out. We don’t look at the production systems that cause this carbon dioxide to be in the atmosphere, or the other, related problems. Many of the environmental policies that we see today from governments across the world take a shallow ecology approach to the crisis: we can keep going, and keep growing, we just need small modifications to stop the worst parts of our production and consumption.

Deep ecology, on the other hand, does take all these problems as being interconnected in one large web. For Naess, deep ecology also comes with certain commitments relating to the order and structure of beings in the world, and a certain ethical view, too.

The two main traits of deep ecology are the following:

- A belief in the fundamental importance of self-realisation. This means that each human should be able to set and achieve their goals and develop themselves as they see fit in any society. Deep ecology extends this to include all living beings, too. Therefore, all bears, birds, fish, snakes, spiders, wasps and more, should be able to flourish on earth, all at the same time as humans are.

- The belief that human beings are not at the centre of the universe (a rejection of anthropocentrism). Ecocentrism is the position that all forms of life are important because they are alive on this planet, and this gives them the rights to live in ways that allow them to flourish. All life forms, and a diversity of life forms, are valuable in their own right. This means that human beings are no longer the masters of nature, the possessors of nature, nor do they have any divine or supreme right to the use of natural resources. The idea that human beings are at the top of the evolutionary pyramid is arbitrary, and this view poses that there is a web, a net, or a fabric of relations, in which the human being is just one part.

Deep ecology says that the reason that we are going wrong is because we have badly evaluated the place that we as human beings occupy in nature. If we are to confront the challenges we face, we have to re-evaluate this, and change our perspective on who we are as human beings in, and with, nature.

Furthermore, Naess posits that a view of cooperation, rather than competition, should be had towards species in nature. He writes, “live and let live is much better than Either you or me.” He also notes that nature, and ecological systems, are complex, but not complicated. This implies a division of labour, not a fragmentation of labour in the way beings work together. Finally, Naess advocates for decentralisation and localisation, so that structures can be developed that reflect the local landscape and ecology in which the human beings live.

The leading theoreticians of deep ecology

Already mentioned is Arne Naess (1912-2009), who was a Norwegian philosopher and writer on environmental issues. He was the youngest person to be appointed full professor at the University of Oslo in 1939, and was the only philosophy professor in the country at the time. He also was a prolific mountaineer, and engaged in several protest actions throughout his life to prevent the destruction of the environment.

Naess created an 8-point platform upon which a deep ecology movement could be founded, with fellow American environmentalist George Sessions, in 1984. These eight points are:

- The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves…. These values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

- Richness and diversity…contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.

- Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

- Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening.

- The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease.

- Policies must therefore be changed…[to] affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures.…

- The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality…rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living.…

- Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to participate in the attempt to implement the necessary changes.

Warwick Fox (b. 1954), an Australian-British environmentalist and Professor at the University of Lancashire in the UK, is another key thinker in developing the deep ecology movement from the ethical point of view. For a decade beginning in 1984, he worked to primarily on deep ecology, before shifting away from this to consider environmental ethics more globally. “Toward a Transpersonal Ecology: Developing New Foundations for Environmentalism” is his main work on deep ecology, where he writes that deep ecology has three main ideas:

- The development of a non-anthropocentric or ecocentric worldview,

- The idea that we should ask deep questions about our relationship with the natural world, and what this means, and

- The importance of cultivating a wider relationship with different forms of life around us.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was another key thinker, or source of inspiration for the deep ecology movement. He is often not cited as a deep ecologist, because of some key differences in his thinking, despite their belonging to deep ecology at first glance. He was one of the ‘fathers’ of the ecological consciousness in the United States, as well as the environmental ethics movements.

Leopold believed that instead of each individual being able to realise his or her own goals in life, the community or group was more important. The community was prioritised over the individual, and should be so in our thinking and policy decisions regarding our relationship to nature.

Leopold also fought for the idea that we do not only have rights to certain resources, but also responsibilities towards nature. He believed that we shouldn’t be giving people money to fulfill their responsibilities towards the natural world; rather, their mere existence on this planet meant that they have the duty to fulfill these obligations.

Central to the thinking of all these people is an idea of egalitarianism amongst all living beings. Human beings cease to be the master species on earth, and instead, all forms of life have equal value and importance on earth. Likewise, they all encourage us to reflect on our relationship with nature, and propose that we should relate more to nature, sometimes in a spiritual way, other times in a metaphorical way.

Earth First, founded by David Foreman (1946-2022) and some of his friends in the southwestern United States, is perhaps the most radical example of a deep ecology movement. Their widely referenced belief was that human beings are parasites on the planet, and should be placed last, rather than first, in the hierarchy of species. This anti-human thinking was too much for many humans who believe in the human race at least to some degree. These radical ecologists refuse to go to commissions or talk to politicians, instead preferring eco-terrorism, protests, blockages, and other radical means to stop environmental destruction. There are now chapters of Earth First in many countries across the globe.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Critiques of the deep ecology movement

On a theoretical level, one of the main problems with deep ecology is that we always end up back in an anthropocentric worldview, no matter how hard we try.

Take for example, the belief that all life has value on earth, and all species are intrinsically important. This idea of value requires an evaluator – someone or thing who can decide what has value on Earth and what does not. This evaluator could only be a human being, because value is a human concept. Despite all life being equally important, there is still one species who is deciding this fact and enacting its consequences.

Furthermore, deep ecology is often charged with being anti-humanist, or worse, anti-human. Humanism is the view that the human being is at the centre of thought in the world, and values the development of human qualities, the love of humanity, the fight against oppression, and more. Humanism constructs a vision of the ideal human, and, by definition, this human is not-nature. Humanism implies anthropocentrism, one of the main things that deep ecology seeks to challenge. Therefore, many deep ecologists are do not mind being anti-humanist, because it is this very thinking, they believe, that has caused the problems in the first place.

Deep-ecology is also sometimes referred to as being fascist, which is a mistaken view, but does have some truth to it. Critiques often talk about the fact that the Nazis in Germany liked writing about nature, and fantasised about their relationship with nature, and therefore that the deep ecology movement is somehow related to National Socialism in Germany. This is incorrect. However, what deep ecology could lead to is a form of ecological totalitarianism, whereby the efficiency of the ecosystem, or the rights of all beings, are taken administratively to be the highest goal, with other things such as human needs, or culture, becoming unimportant to a particular politician. This is not inherent to the deep ecology view; rather a possible manifestation of deep ecology that should be avoided. Arne Naess is rather anti-fascist and anti-totalitarian: he asks that each human being search for the meaning of their own life, and that the possibilities be afforded to them to be able to do so.

Deep ecologists also sometimes discuss the problem of population and the overconsumption of resources. Each year, human beings consume more and more resources, at a faster rate, and therefore consume more than one planet’s worth of resources per year to meet their supposed needs. Deep ecologists like Naess as well as other ecologists such as James Lovelock (the Gaia theorist) have supported a reduction of the human population. The optimal human population, according to them, sits somewhere between 100 million and 500 million. The problem with this, however, is that there is no ethical or morally justifiable way of reducing the human population without imposing some kind of rule on who can, and who cannot, have children.

Finally, the deep ecology perspective is often situated in religious or ideological contexts. People such as American Joanna Macey mix Buddhism and deep ecology to advocate for a return to nature and the natural world. There is something spiritual about the deep ecology movement, and the changing relationship that this movement advocates between humans and nature often forces us to think in spiritual or somewhat imaginary ways. For some, this approach works and is necessary; for others more scientistic in nature, this is another criticism of deep ecology.

In summary

The deep ecology perspective, and the movement that accompanies it, seeks to challenge the position of the human being in nature. Instead of being on top of the hierarchy, or standing outside of nature, human beings are embedded in the natural fabric that makes up nature, and are but one species in this fabric. Rights to resources are to be accorded to all living beings, and not just to human beings.

Deep ecology has challenged how we relate with nature, and has promoted an awareness of all other life forms on the planet. It proposes radical political changes, like giving rights to all living beings, which in practice seem, at least at this stage, quite difficult to implement.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

A history of ecology

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 11/05/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology

share

Ecology is a relatively new science, and an extremely complex one to pin down. It’s also stuck between competing world views which mean that sometimes ecological information can be used to justify something when in fact it can only support an argument, rather than justify it. Knowing the history of ecology means that we can better understand the role it plays in our societies and the considerations of our future planet.

Ecology is the discipline which studies phenomena such as climate change, the extinction of species, global temperature increases, sea level rises, and more. Some 200 years ago, ecology wasn’t really a thing, and even biology only really began to be developed as a separate science in the 19th century. The origins of exploring the relationship between humans and nature using the scientific method are much more recent than we might think. However, the discovery of climate change and the potentials for increased carbon dioxide to warm the atmosphere are not as recent as we often make out. In fact, in as early as 1863, British physician Joseph Tyndall suggested that carbon dioxide and water could potentially provoke a change in climatic conditions, based on his studies of the absorption of light by gases.

There are some challenges to writing a history of ecology, not least the fact that each country, culture, religion, and people have a different relationship to or with nature. This means that their ‘ecology’ or ‘economy of nature’ will be different. What we commonly call ecology in the English-speaking world has largely been influenced by North American research and priorities, mostly in military and security. Other countries, such as Russia, have contributed much to ecological science historically, however the Soviet Union regimes have meant that this did not continue. Māori have their own relationships to nature, and each iwi or tribe will relate to their environment in a different way. Is the study of this ecology? Or is this something else? In this article on the history of ecology, we’ll stick to understanding ecology in a scientific and mostly western sense, drawing on the history of the study of natural relationships from a scientific perspective. This does not mean that other, indigenous cultures do not have an ecology, or that their ecologies are not important. Rather, we should understand their relationships to nature using their language and in their context.

What is ecology?

Ecology, broadly speaking, is the study of living beings and the relationships between them, between these beings and their environment, and of the biological factors of the environment. Ecology studies things like ecosystems, which are specific containers of life on earth which work according to certain patterns and tendencies. Ecology also studies the biosphere, or the whole area in which living beings exist on the planet. In more recent times, ecology has been more focused on the relationship between humans and nature, than other relationships. This is because of the discovery that human beings are destroying the continued viability of life on earth through their production and consumption activity. This destruction has manifested in climate change, the acidification of oceans, rising sea levels, rising temperatures, the loss of animal and plant species, and much more.

There is a problem in defining what the boundaries of ecology are, however. Think about how we use the word ‘ecosystem’ or ‘climate’ to talk about start-ups or just groups or communities of things. These are terms which are proper to ecology, and not to other disciplines or areas of life. But if ecology is the study of ecosystems, then we must say which type of ecosystem we are studying: probably not the start-up ecosystem, that’s for sure! There are also an increasing number of small disciplines appearing, which branch off from ecology, such as the ecology of gender, ecology of words, ecology of music, and much more. These are more difficult to place, because ecology does look at the relationships between living beings, therefore, between human beings, too.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

A quick overview of the stages in ecology’s history

Yannick Mahrane writes that there are three main stages in the development of ecology (in “Ecology: Know and Govern Nature” (French)). Each stage relies on a different metaphor or way of seeing nature, which influences the nature of the science that is being performed. Other writers will discuss the development of ecology in terms of paradigms, or main assumptions that theorists make. Yet more will talk about ecology in terms of the debate between holistic theories, which view the earth or living beings as a united system, and reductionist theories, which look at the parts of these systems separately.

According to Mahrane, the first stage of ecology was from the word’s coining by Ernst Haeckel in 1866, until the end of the Second World War in 1945. This period was characterised by the study of plants, which developed in order to control territories, regulate and improve agricultural production, and learn about how plants functioned through institutions such as Botanic Gardens. These scientists had an organicist ontology, meaning they viewed the world as a unified whole, and organisms within this system are constantly changing and evolving.

The second stage of ecological development is from 1945 until the middle of the 1970’s. This stage is characterised by a formal, mathematical ecology, which functioned on a culture of engineering and geo-engineering. This is when we saw the large attempts to build domes and controlled environments by people such as Buckminster Fuller, which ultimately failed. These ecologists thought in mechanistic and cybernetic terms, meaning that they viewed the world as composed of mechanical parts which all needed to be understood in order to understand the whole. This viewpoint is also called reductionist.

The final stage in ecological development is from the late 1970’s until today. Here, ecology becomes influenced by neoliberal politics. We begin to view ecosystems as providing us with services, which need to be accounted for and managed. Managerial ecology views nature as something to be directed, and human beings are the designated managers of this nature, performing a very similar role to managers in companies. Economic rationality, in terms of resources, production, consumption, and more, are key to the viewpoint that this kind of ecology takes.

The beginnings of ecology

We could think that ecology first began as a systematic study of nature with Aristotle’s natural science, in Ancient Greece. This was not called ecology at the time, but Aristotle made detailed observations of many animal and plant species, noting their qualities and relationships, and drawing differences between the varieties and species that he found. Theophrastus, around the same time as Aristotle, also commented on the relationships between living beings.

The second possible beginning of ecology is with Carl von Linné’s economy of nature, entitled Systema Naturae, spanning 3 volumes and 2,300 pages. His method was to identify, name and describe as many different species as he could find, and determine the hierarchy or relationship between these different beings.

Biology as a science began to appear in the 19th century, and people such as revolutionary biologist and evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin began positing their hypotheses concerning the natural world, and how this natural world had developed. At the same time, Ernst Haeckel in Germany begins referring to something he calls oekologie (ecology) – the economy of nature, which he defines as the study of the relations between organisms:

“By ecology, we mean the whole science of the relations of the organism to the environment including, in the broad sense, all the “conditions of existence.” These are partly organic, partly inorganic in nature; both, as we have shown, are of the greatest significance for the form of organisms, for they force them to become adapted.” E. Haeckel, 1866 Generelle Morphologie der Organismen.

This definition of ecology will be expanded upon, throughout the rest of the history of ecology, because ecology does not only study living beings, but also the environment, the ocean, the soils, and more. It also is concerned with other types of living and non-living things, not only that which we would normally call ‘organisms.’

The invention of some key concepts in ecology

In the late 19th century, there were some central developments that helped ecology to become a domain in its own right. These were the invention of the concept of the biosphere, and the creation of ecology’s research method, the quadrant.

In 1875, Austrian geologist Edward Suess invented the term biosphere. He did this in the context of a changing Europe: no longer was Europe composed of feudal communities; rather the industrial development and the creation of nation states was beginning to change the way people lived, and saw the world. This increase in industrial action and production meant that people began studying the impact and the relationship between humans and nature. They could see that something was happening, and that landscapes were changing, so scientists began investigating this.

It would only be in 1926 that the idea of the biosphere could really take hold, as a result of the Russian-Ukrainian philosopher and ecologist, Vladimir Vernadsky. In his book, The Biosphere, he posits that life is the geological force that shapes the earth, and that terrestrial life can be considered as a totality – in a global sense. Instead of thinking about small localised ecological events, there is a linking and intimate relationship between all life on earth. This concept of the biosphere is one view in the holistic perspective in ecology.

Across the Atlantic in the United States, Frederick Clements developed the concept of the quadrant: a square, usually 5 metres wide and 5 metres across, in which all life forms would be studied to build a picture of a particular area. Clements wrote a how-to guide for ecology, measuring out quadrats, counting species, and measuring conditions. It was later that more statistical and sophisticated measurements were added to these methods, to reach the forms that we have today.

The ecosystem

The idea of the ecosystem is another key concept in ecology that has only grown in popularity since its coining in 1935. It was not, however, until the 1950s that ecosystems became a central notion for ecologists worldwide.

Between the World Wars, most ecological thinking was dominated by Clements’ theories, which considered ecological communities as organisms and associations, buoyed by his methodology of the quadrant. British ecologist Arthur Tansley developed the idea of an ecosystem in his work “The use and abuse of vegetational terms and concepts” to once again shift the paradigm in ecology. His interest in ecology, as for most ecologists, was due to a larger scale industrial revolution, and an increasing globalisation, which were beginning to reveal negative flow-on effects on the environment, and on our ability to produce food for larger populations.

Tansley considers ecological communities as totalities, and not separate species with no relations between them. This again is a holistic perspective. The ecosystem is a way of referring to these ecological communities of related plants and species in a particular place. However, Tansley is very keen to point out that the ecosystem is not a given concept in nature: we cannot see ‘ecosystems’ nor can we find them somewhere. Rather, ecosystems are mental abstractions, ways of seeing communities of living beings, such that we can better study and understand the relationships between living beings in a particular area. We should not forget that ecology produces models of the world, and all models are wrong – they are simplistic representations of what reality is actually like, but we use them because they help us to understand what the world is like.

Linked to the idea of the ecosystem is the particular relation within this system between living beings, called the niche. Charles Elton, the pioneer of animal ecology, used this term to describe the place occupied by a particular being in relation to other beings. The niche is “the position of the animal in its environment and its relations to its food and to its enemies.” (Animal Ecology, p. 63-64).

Another paradigm shift, this time with energy

As industrial societies began to electrify large parts of the home and office, energy transformation and electricity transfer became important topics in the minds of many scientists. This change did not escape ecology, with Howard Odum, a North American ecologist, positing that energy is a universal perspective through which we can see the world, particularly in the way that human beings use nature. Photosynthesis – the way that plants capture energy from the sun – is one such way of considering energy transfers, and opens up a realm of considerations regarding the efficiency with which plants convert energy into mass or food that we can eat.

Along with Odum, Raymond Lindeman believed that ecosystems were actually thermodynamic systems, which exchanged energy with their environments. An ecosystem could be seen and determined through analysing energy transfers. Take a corn field, for example. The corn plants take up nutrients and water from the soil, and sunlight from the sun, which they convert into energy in order to grow the plants. Other organisms in the corn field, like the worms in the soil, the bugs on the plants, etc. all take energy from their surroundings, and convert it into energy that they can use to sustain their life. Human beings do the same thing – we eat food and drink water, which we extract molecules of glucose from, in order to have the energy to perform.

The third paradigm shift: mathematical ecology

Between the two World Wars – the late 1910’s and the late 1940’s – ecology was in its golden age, as Jean-Paul Delèage put it.

The first attempts at mathematical ecology were with Thomas Malthus’ writings on human population. In 1798, he published “An Essay on the Principle of the Human Population” where he compares human population growth to resource availability on Earth. He notes that human populations double: they follow the pattern, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32… Resources, and our subsistence, however, grows following an incremental increase: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Eventually you will have a population of 256, but resources will have only grown to 9 – therefore showing that at a certain point there are limits to population growth, because of a lack of resources available for these populations.

Along with this conclusion, resources were becoming scarce and ecological problems were beginning to emerge in the growth of food and the availability of wood for fuel. Mathematical and statistical formulations became a key way of understanding, and therefore predicting, what would happen in certain ecosystems that were crucial to human survival.

Alfred Lotka (in 1925) and Vito Volterra (in 1926) produced ecological models for competition and predation in nature. They wanted to find out how certain animals became the prey of other animals, and what this did to their populations, depending upon the population of the predator. Central to their ideas was the observation that animals in nature seemed to compete for resources and space, and the availability of these things determined the relative success of their populations.

The introduction of past events into these models by these two researchers meant that the models became more complex. It also gave a sense of history to the things that were happening in nature: what happens now depended upon what happened in the past, and we began to be able to make mathematical connections between past and present, and therefore understand what might happen in the future.

Edward Wilson then built upon these ideas, which were for him too simplistic, to develop the idea of dynamic equilibrium. These mathematical models were reductionist – they wanted to understand species, and could not include in their models all the conditions that affected the populations of a specific species – climate, food, predators, other species, catastrophes, viruses, bacteria, and more.

The idea of an equilibrium is similar to that which we find in economics, and Yannick Mahrane suggests that there is a link between the era in which the idea of market equilibrium took hold in Western societies, and when it became an ecological concept, too. Wilson’s idea is that species in a particular ecosystem will reach a stable point of equilibrium, where certain populations are able to be maintained according to the resources. When something in the ecosystem is disturbed, these relative populations will change – the point of equilibrium will move and re-establish itself at different levels to before.

The theory of Gaia

Building upon this idea of equilibrium and changing points of stability, British scientists James Lovelock and Lyn Margulis developed the hypothesis of Gaia, which unified the concepts of biosphere and equilibrium in the science of ecology.

The Gaia hypothesis sees the earth as a living being itself, which is capable of self-regulation and self-organisation of the climatic conditions and the life forms that exist on the planet. This system, called Gaia, is much larger and more inclusive than the biosphere; it includes places where there is no life as well, such as the atmosphere, the oceans, and the rocks.

The key part of the Gaia hypothesis is that the living beings on the planet participate themselves in the regulation of temperatures and the composition of the surface of the planet. By breathing in and out, we take out oxygen, and release carbon dioxide. Trees take up that carbon dioxide, and release oxygen. The earth is no longer just something that is there, created in a certain way; rather it is the product of the life forms that have inhabited it. The proof for this hypothesis is the fact that many millions of years ago, when life first formed, there was no oxygen on the planet. Through the activity of bacteria, however, oxygen was released into the atmosphere, and then reached a stable level of around 21% of the atmosphere, which was the most ideal composition for the regeneration of forests, the growth of other species, etc. This world, therefore, is the best possible world for those species that are living on it, because they have participated in creating the conditions that now exist to support life.

This theory is termed a hypothesis because it is still hotly debated. The main reason for this is that the theory posits a certain teleological finality to the planet: there is a goal to the evolution of life on earth. It is not just random happenings that occur in certain ways that just so happened to create life and sustain life. This goes against much of the fundamentals of the sciences. Furthermore, the theory is supported by certain life forms above ground, but in the oceans, marine life seems to be much more determined by nutrient availability than temperature or composition.

We can, as Stephen Schneider suggests, take a key conclusion from this theory as truth: that organisms interact and co-determine their destiny. What this destiny may be is not defined, nor is it possible to know, but what we can know is that different forms of life are interrelated and are involved in determining the success of other forms of life on Earth.

The human being in ecology

As we became more aware of the fact that human beings are affecting the composition of the atmosphere, the quality of the soils, and the viability of other life forms on the planet, the object that ecology studied began to change. Instead of looking at ecosystems, ecologists began to study the biosphere – the totality of life on earth – in more detail.

Looking through the history of human civilisations, we can see a very strong correlation between the climatic conditions at a particular period in time, and the economic success of these civilisations. Although the ancient civilisation of the Maya in South America did not decline solely because of ecological reasons, the destruction of forests and the disruption of the water cycle contributed to the collapse of this civilisation. The cultivation of corn was the main factor in this disruption, and as they tried to grow more corn, they disturbed larger parts of the ecosystem upon which they were reliant.

Pierre Gourou, a French geographer, noted that “there is no crisis in the usage of nature that is not also a crisis in the way of life of mankind.” Our relationships with nature became more and more important as objects of study and analysis, to find out how we were changing the ecosystems in which we lived, and the biosphere as a whole. In the United States, and other countries, large areas of land have been rendered unusable and infertile because of the industrial agricultural methods that were, and to some extent still are, used to grow food for both humans and cattle that we eventually eat.

Ecologists, and political or literary ecologists, began to think about where this problem might have come from. Why and how did we get into this mess? These more theoretical and philosophical forms of ecology began to flourish around the 1970’s, and are perhaps still in their main growth phase today. Lynn White in her 1967 essay, “The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crisis” traces back the origins of this relationship to nature to the Bible: we were told that God had given us the Earth to have dominion over, and to fill this Earth with our own kind. Francis Bacon, an English philosopher and statesman in the 16th century, made clear that human beings were the centre of the universe, and had absolute authority over all things on Earth.

The 21st century ecologist is therefore confronted with the question of the place of the human being in the biosphere. What role do they have? What impact do they have? And how can they live with, or without, nature? These questions are just as much scientific as they are philosophical, which is why ecology is now a discipline at the crossroads between multiple different areas of study and research.

Ecology is also still very much in a phase determined by neoliberal economic theory, whereby accounting for and quantifying resources and outputs is crucial to the work of many ecologists. Carbon accounting is but one example of this kind of ecology, whereby we attempt to figure out the carbon emissions of each resource and good on the market, and each process or action undertaken in society, so that we can develop an overview of the carbon emitted per year, per country. Once we can measure and know about it, then we can solve it: so would say the technologically-minded politician or leader.

Ecology has many challenges in the 21st century, not least the need to research the ongoing impact of human beings on the planetary systems and climate conditions. The challenges that ecology faces are only increasing, however, with the rise of a distrust in international organisations such as the IPBES and the IPCC, both tasked with reporting on the human impact on nature, as well as climate-skepticism, climate reassurism (those who say we don’t need to worry about climate change), and scientism (those who believe that science will solve all the problems). Disseminating and communicating the research and results of ecology, as well as the nuances about the predictions made and methodologies used in ecology, is another incredibly difficult task.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

IPCC Synthesis Report: what we do now will determine the future impact of climate change

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 12/04/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology, Essential, Politics

share

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have finished their sixth cycle of reporting. They published the conclusions of this research in a report released in March 2023.

In late March 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released the final synthesis report of around a decade of research and investigation into climate change and its impacts and effects. This report is incredibly important, as it shows us an overview of what we currently know at a global level, as well as a regional level, about the impacts climate change might have on our environment. The report contains the best guesses about what could happen, and presents future scenarios with different levels of global warming to show us what these futures might be like. What’s clear is that each tenth of a degree makes a difference to the damage that will be caused by human-induced climate change.

Unfortunately, there was not much fanfare or media reporting in New Zealand when the report was released. A look on the Climate page of Stuff’s website 3 weeks after its release shows nothing regarding the report, and to find the articles they did publish requires searching through their archives. Looking at the articles, no news media site seemed to take the time to explain the whole report, its importance, and what NZ could do off the back of this evidence.

What is the IPCC and why is this report important?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC for short, is the organisation set up by the United Nations (UN) to coordinate and report on climate change science across the globe. It comprises scientists from member nations of the UN, each a specialist in their field of climate research in their country.

The IPCC is divided into three Working Groups, who focus on different areas of climate change research. The first group works on the physical science of climate change; the second on climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, and the third on mitigation of climate change. There are also Task Groups which focus on research in specific areas such as gender-related impacts as a result of climate change.

The IPCC have reporting cycles, meaning that approximately every seven years they release three large reports, one from each Working Group, and a synthesis report, which summarises the findings over this period. In 2022-23, they released their sixth cycle of reports (AR6), which discuss the changes in climate science since 2014, when the fifth cycle was published. The report published in March 2023 was the final report in the cycle, synthesising the findings and delivering important conclusions and possibilities for action for governments worldwide (link to the report).

It’s important to note that the IPCC do not recommend anything, nor are they in the business of making promises of what will happen. They discuss the information that they have gathered through the scientific method, which comes with varying levels of certainty, depending upon many other factors, such as the availability of data, the extent to which this data has been verified, and the likelihood of certain scenarios. The IPCC reports can tell us the overall impact of certain policies, but they will not tell us what to do or how to do it.

We must therefore be careful when reading articles which quote a conclusion from the IPCC report, attempting to defend the arguments of a particular person. The report does not justify actions, but provides evidence for the possible outcomes of global warming. Limiting warming to 1.5 degrees is of interest to the scientists; just how we go about that is of interest to politicians.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

The main conclusions of the Synthesis Report of the Sixth Cycle

There are several important conclusions drawn by the report that all citizens should be aware of, if they are to understand climate change and its current and potential future impacts. These are the following:

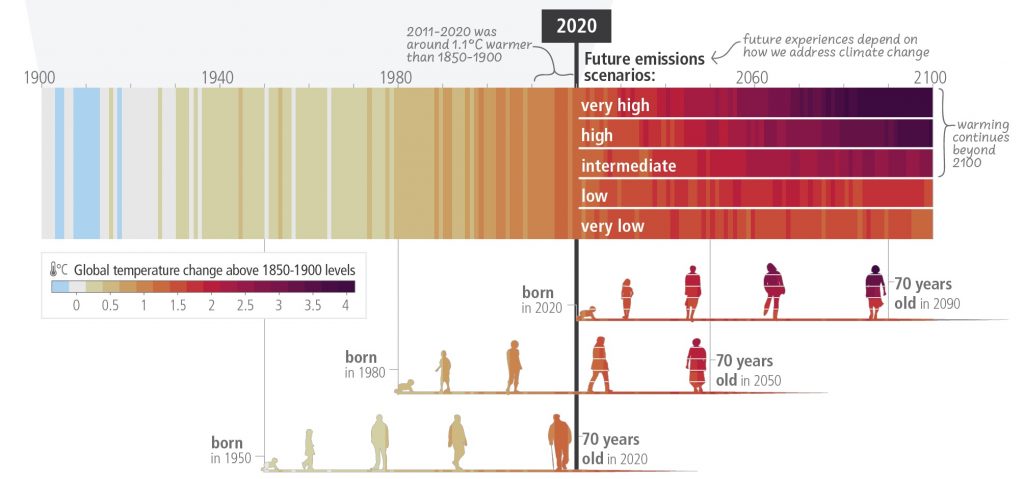

- Global warming has already resulted in a temperature increase of 1.1 degrees Celsius in the period 2011-2020, compared with 1850-1900.

- Time is running out. There is a rapidly closing window of action to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all, and if we do not see a rapid and severe decline in greenhouse gas emissions, we will not keep global warming to 1.5 degrees, and therefore the challenges will become more complex and the impacts and risks more severe. The next 10 years are crucial.

- Each tenth of a degree counts. Each tenth of a degree of warming results in greater losses and damages, and risks that become much harder to predict and to manage. Current measurements are showing the state of the planet is worse than was predicted in the previous report.

- Vulnerable populations are the first and hardest hit by climate change. These populations are less developed countries, indigenous peoples, low-income families, and those living in low-lying and coastal regions and small islands. 3.3-3.6 billion people live in highly vulnerable places to the effects of climate change.

- There is a gap between what we are currently doing, and what we should be doing to both meet our targets and keep global warming within the 1.5-degree threshold. Continuing our current trajectory will result in 3.2 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100.

- All models desiring to limit the impacts of climate change at least somewhat involve a necessary “rapid, deep, and in most cases immediate reduction in CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions across all sectors.”

- Cross-sector, multidisciplinary and democratic approaches are the best ways to implement and adapt to climate change, as well as mitigate losses. Working with indigenous knowledge, working with diverse approaches, working with vulnerable populations, and involving all stakeholders in decision making leads to better outcomes.

- It is more likely than not that we will hit at least 1.5 degrees of warming in the early 2030’s, however we do have hope. We can still limit warming to 1.5 degrees. The only way to do this would be through large, severe cuts in emissions across all sectors and all developed nations on the planet.

The estimates: What will happen at different levels of warming?

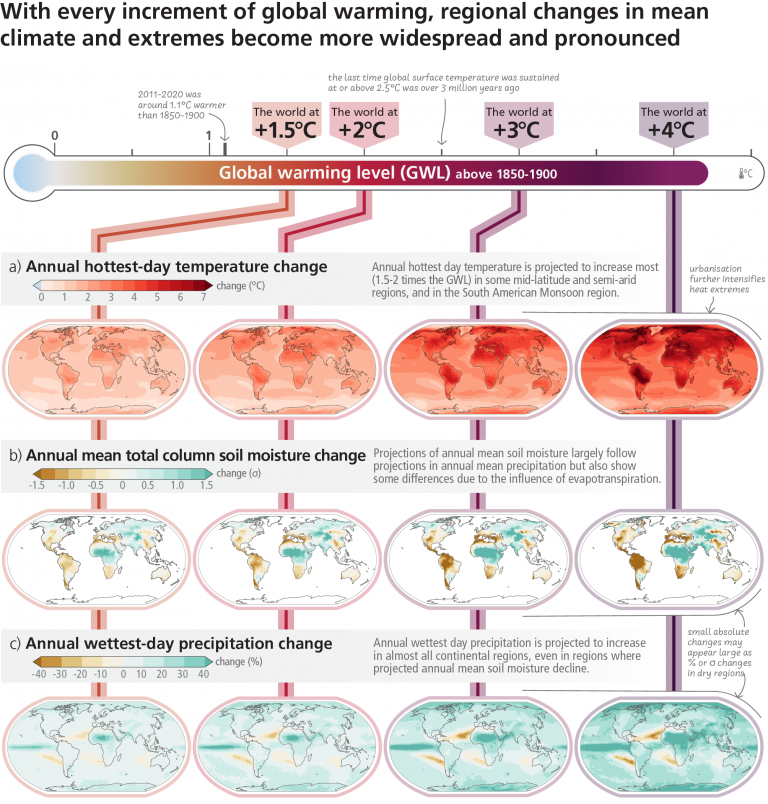

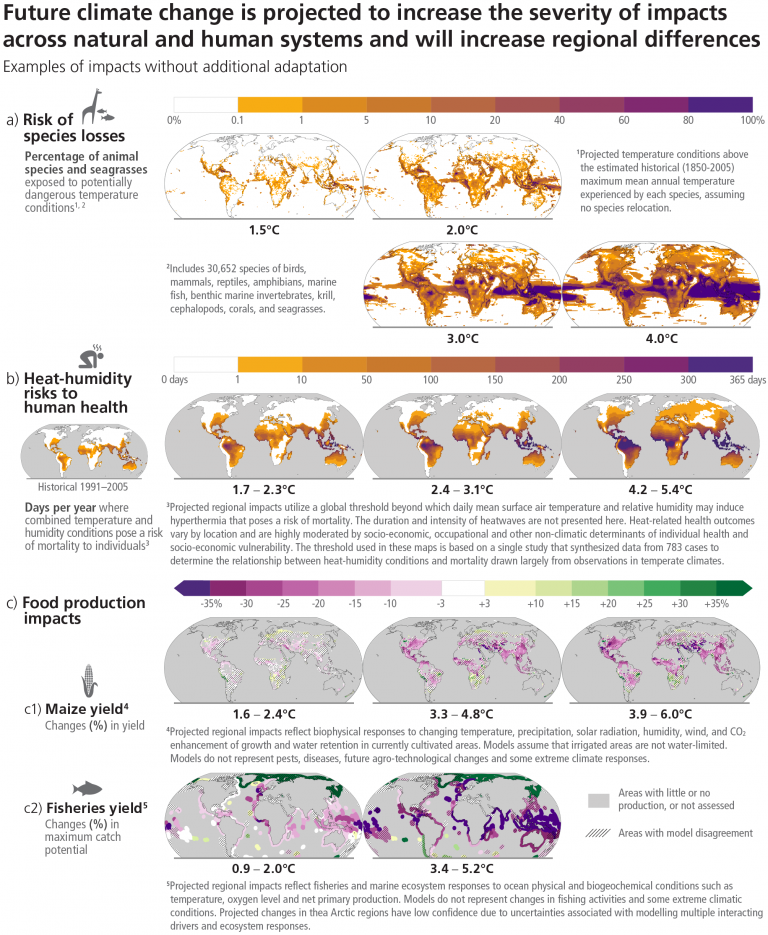

The image below contains the IPCC’s estimates for all geographic regions at different levels of warming. The first scenario is for 1.5 degrees of warming, the last for 4 degrees of warming. As you can see, the impact gets more and more severe, as the average temperature increases.

The report notes that every region is projected to increasingly experience extreme weather events, which happen concurrently. This means that both hottest temperatures will increase, and lowest temperatures will decrease, as well as there being increased precipitation and risk of rain-caused flooding in most regions, increased fire risk, tropical cyclone risk, and drought risk.

For other terrestrial species like insects, mammals, birds, etc., of the tens of thousands of species surveyed, between 3-14% of them face a very high risk of extinction at 1.5 degrees of warming. Coral reefs are projected to decline a further 70-90% at 1.5 degrees – these may very well become something that exist only in our memories.

Alongside these ecosystem changes, we can expect changes to the availability of food, and therefore increases in nutritional deficiencies among those in highly vulnerable regions; increases in pathogens and diseases, heat-related deaths, and more. As the temperature increase rises, so does the complexity of managing the effects of this increase.

Current policy action vs necessary policy action: the enormous gap

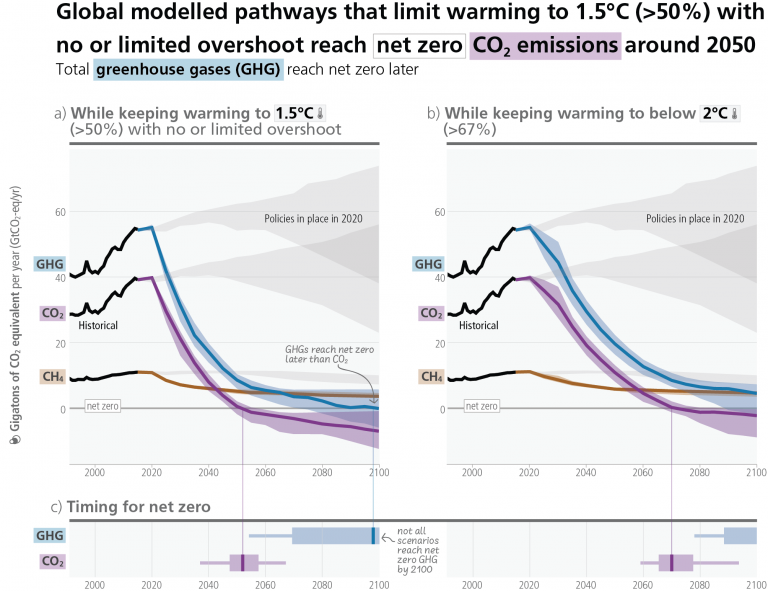

If the policies and agreements in place in 2020 such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, were continued along their current trajectory, we would in no case reach net-zero emissions, nor keep warming to 1.5 degrees. There is a large gap between the current policies in place, and what needs to be done in order to respond to the dangers that we just saw above.

In the case of finance, globally we need 3-6 times more investment in climate-related programmes, initiatives, innovations, strategies, and knowledge production, averaged between now and 2030, if we are to limit the effects of global warming. In the Australia, Japan and New Zealand region, this figure is 3 times more at the lower estimate, and 7 times more at the higher estimate. For places like the Middle East, a much, much larger investment is required, with 14-28 times the current investment required to mitigate the effects of climate change. The report notes that “There is sufficient global capital and liquidity to close global investment gaps, given the size of the global financial system.” Factors within and outside the global financial system act as barriers to stop this from happening.

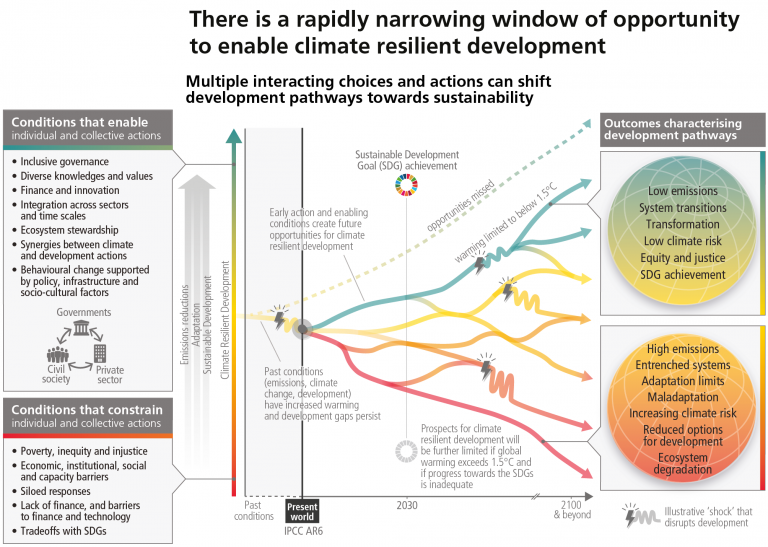

The most important conclusion of the report is that what we do between now and the early 2030s, is what will make the most difference to the impacts of climate change for all future generations. Sea levels will keep rising for millennia, but just how much they rise is determined by how we choose to respond today. As you see in the above image, when we choose early action, we can set a trajectory towards a brighter, more stable, and more liveable future. If we make bad choices now, we put ourselves on the pathway towards greater destruction, pain and suffering in the future.

The good thing is that the report highlights the interrelatedness of the Sustainable Development Goals and the work being done to mitigate the effects of climate change and adapt to new realities. In places where we eradicate poverty, ensure clean air and water supplies, and educate all young people, we not only look after the ecosystems and allow communities to reduce their emissions, but also improve the wellbeing and living standards of these people. There may be some trade-offs between climate mitigation and sustainable development, but there are significant mutual benefits, too.

What can we do about climate change?

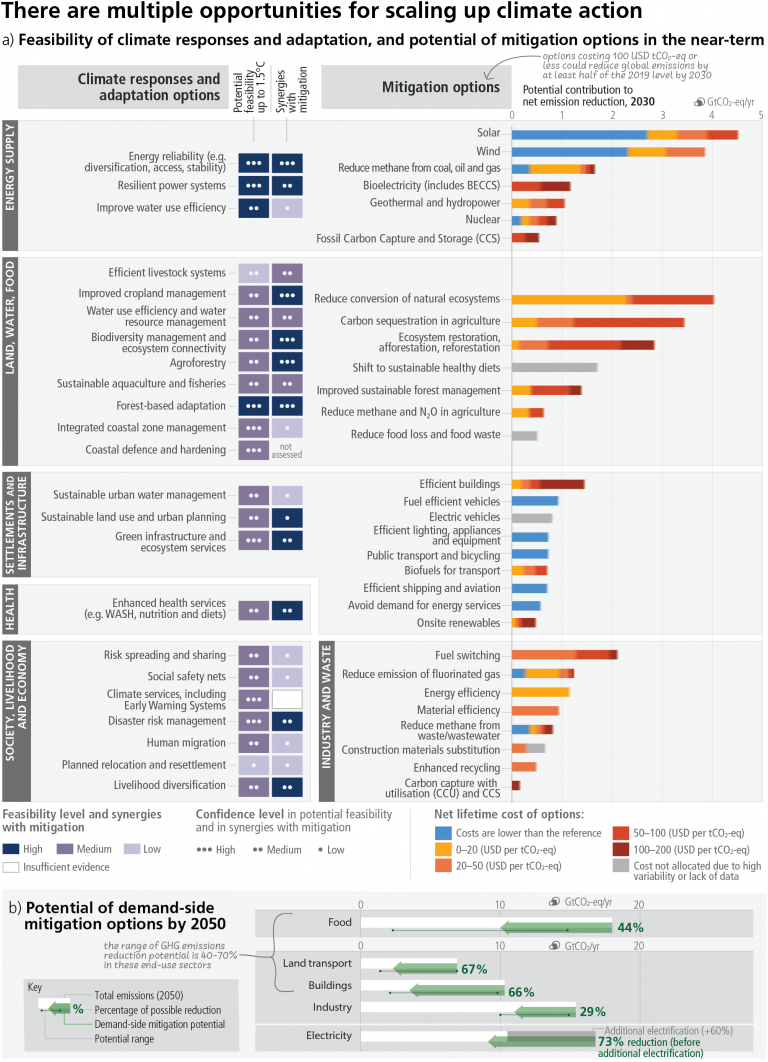

The Synthesis Report considers many different possibilities for climate action. These possibilities are both at the individual and collective level. Have a look at the image below, and you will see the various estimated impacts of particular solutions, as well as their relative costs to implement. The largest light blue bars represent low-cost high impact solutions, such as solar and wind energy, electricity efficiency, and public and goods transportation including cycling.

Things that we can choose to act on ourselves include our diet and lifestyle choices. As we can see, shifting to sustainable healthy diets with more plant-based foods and less animal products such as meat and dairy has a reasonably large potential impact. Likewise with reducing food loss and food waste – only buying what we need and making use of all of it can go a long way to reducing emissions.

Similarly, transportation choices make a big difference. Walking or cycling are the lowest-emission options, closely followed by public transportation. A fuel-efficient vehicle or electric vehicle if you do need to use a car also makes a big difference. Our shopping choices also make a difference, opting for efficient lighting, efficient household appliances, and other electronics which require lower energy supplies helps to reduce emissions.

This individual impact is summarised in the Demand-side impacts section at the bottom of the image. Sobriety, that is, making the choice to live a low-emissions, low-energy, low-consumption lifestyle, has the potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40-70%. Given that each tenth of a degree counts, these lifestyle and shopping choices makes a real difference.

Most of the impact does however come from the institutions which make up a society, including government, businesses, and energy production. We can’t make the choice to use solar or wind power unless we have a large investment ready to purchase an autonomous power supply for our own roof, but our energy companies can make the decisions to stop fossil fuel energy production. Solar and wind energy are low cost and high impact solutions. Stopping deforestation and the destruction of natural ecosystems is a reasonably low-cost solution which likewise has a large impact. These kinds of decisions are the policies we need to see our politicians enacting, if they are to demonstrate that they have understood the problems we will face due to climate change.

The report puts specific emphasis on the fact that justice and inclusion are particularly important in the response to climate change.

“4.4 Actions that prioritise equity, climate justice, social justice and inclusion lead to more sustainable outcomes, co-benefits, reduce trade-offs, support transformative change and advance climate resilient development. Adaptation responses are immediately needed to reduce rising climate risks, especially for the most vulnerable. Equity, inclusion and just transitions are key to progress on adaptation and deeper societal ambitions for accelerated mitigation. (high confidence)”

Likewise, solutions that involve multiple stakeholders, and which are arrived at through collaborative means, have far-reaching impacts beyond just the state of the planet:

“4.9 The feasibility, effectiveness and benefits of mitigation and adaptation actions are increased when multi-sectoral solutions are undertaken that cut across systems. When such options are combined with broader sustainable development objectives, they can yield greater benefits for human well- being, social equity and justice, and ecosystem and planetary health.”

Some policy ideas

We need to demand more from our politicians, because as the report clearly states, current trajectories are not sufficient to mitigate the effects of climate change. As a reminder, current efforts put us on track to reach 3.2 degrees of warming by 2100. That means, if you are now 30-40 years old, and we continue as we are, your children or grandchildren will be living in a highly uninhabitable world with large-scale economic and ecological damage.

Here are some things New Zealand and other developed countries could do on the back of the IPCC’s Synthesis Report. These are not part of the report, as the IPCC is not involved in making recommendations or telling us what to do; rather they are my own ideas based on the evidence we find in the report.

- Stop all fossil fuel subsidies, spend the money saved on vulnerable populations.

- Convert 100% of electricity grid to renewable (solar, wind as first choices)

- Small scale grant programme for community ecology and environment initiatives (max $20,000 per year, per initiative for example)

- Banning greenwashing with severe punishments, increasing requirements on green advertising, carbon reporting, and introduce mandatory emissions labelling

- 1 day per week environmental work scheme, paid for by the Government (instead of working at your workplace, you opt to work in local government, or other associations on environmental issues, and your daily salary paid for by Government).

- New Zealand international cooperation with low-lying Pacific nations on a much larger scale.

- Free ecological and environmental studies programmes, climate change information sessions for all NZ citizens.

- Investment priority in public transportation, cycling and pedestrians. Development of road and car projects scaled back significantly. Bike and electric bike rebates (50% off up to $500 per citizen for example).

Moving from science to action

The report is serious and sobering reading. It’s quite tough to think about what the world might look like in 20 years’ time. One of the best ways to confront this is through taking practical action steps in your own life to reduce your ecological impact and your emissions. Here are three ways you can transform your new knowledge into action immediately:

You can calculate your approximate carbon footprint using the NZ-based calculator FutureFit here.

You could think about diet and lifestyle changes that you could implement, focusing on food, transportation and energy use. How can you live better, with less?

You can have a conversation at your workplace about your company’s emissions and ecological impact. Push for more measurements of emissions, and more ambitious emissions reductions targets. Use the information in this article to help you talk about what the dangers of climate change might be, and why we should act now.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.

A simple guide to the Global Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 17/02/2023

- Ecology

share

One of the best ways to learn about the ecological crisis is through the reports issued by collaborations between many international scientists. These offer a global and diverse perspective on just what is happening at each corner of the globe, as well as a synthesis of the many different articles published each week on the climate and biodiversity loss.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has 123 member countries, and in 2019 released their 1,000-page report on the state of Earth’s biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Part of the reason why these kinds of reports don’t appear in the news in most countries is simply because they are too large and too complex for any journalist without ecological training to understand. Even with the summary at the beginning, they tend to be filled with ecological terminology and scientific language which isn’t easily accessible for a wide audience.

What is the report about exactly? It’s a collaboration between different governments on the recent changes in the systems of planet Earth, caused by human activity. They look into what the causes of the changes to the Earth’s systems are, why and how the systems are changing, and what this might mean for us going forward. Instead of studying one particular ecosystem by a beach or in a field somewhere, this study brings together research and experience from across the planet to see what is going on, on a global scale. Much of the research has been done since the 1970’s, when world governments first became aware of just how bad things were getting.

The main idea is to see the trends over the past 50 years, and what these trends might mean for the next 30 years, between now and 2050, if we continue down the current path. The researchers also examine other possible scenarios based on popular approaches to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss at the global scale.

The good aspects of this report are its specific emphasis on indigenous and local knowledge systems, its inclusion of diverse perspectives and worldviews, and a gender-diverse team of scientists and researchers. Together they seek to explain the connections between humans and nature, and the impact that human beings are having on Papatūānuku Mother Earth.

The main conclusions

Over the past 50 years, the human population has doubled, the global economy has grown fourfold, and at the same time, ecosystems are increasingly struggling to keep up with this level of development, and are at risk of collapsing in every country on the planet, even with land managed by indigenous peoples. Biodiversity is projected to continue to decline, and human demand for natural resources is projected to increase.

The factors that have caused these changes in Earth’s systems have been changes in land and sea use (for forestry, agriculture, etc.), direct exploitation of organisms, such as hunting, fishing, etc., climate change caused by the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, pollution both of the atmosphere and the soil and water systems, and what they call the ‘invasion of alien species,’ animals and plants that are not normally found in a particular landscape but have been brought in by humans and have taken over that landscape. All of these factors are directly related to human use of natural resources – both in order to meet our needs, and in some cases in attempts to sequester carbon into the ground, which also causes ecosystem disruption.

This disruption of ecosystems threatens their stability – if you start rocking a rowing boat side to side, you have a greater chance of capsizing – which is exactly what is happening here. Only, once we have capsized, or completely disrupted the systems that feed us and meet our needs, we have no idea how to restore them.

Another problem is that we are losing variety in our species of plants and animals, which is also threatening the ability of these systems to combat the other changes that are happening around them. This is called a loss of genetic diversity, and more generally, a loss of biodiversity. As a result, agricultural systems are less and less able to resist pests, pathogens, and the ravages caused by climate change.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

Progress made so far and trends for the future

The report has a frank and alarming conclusion regarding how we are currently faring with regard to biodiversity and ecosystem services: “Goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories, and goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors.”

What they mean here is that if we continue as we are, adding small modifications to systems in place and pulling economic levers to solve the problem, we will not meet the Sustainable Development Goals (for 2030) nor the Aichi Biodiversity Targets (from 2020). Current ecological decline is projected to undermine progress made in 80% of the Sustainable Development Goals. We cannot solve the current problems by doing more of what we are doing now: it simply won’t work; we will just go backwards.

These international and diverse scientists, using research published internationally, support transformational change. By transformational change, they mean “a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic, and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values.”

This is much more than just letting the emissions trading scheme do its thing. It’s also much more than increasing conservation efforts, and planting more trees. Systemic changes at the economic and social level means reorganising our systems of production and agriculture, it means consuming less and producing less waste, and ultimately, it means abandoning our “current limited economic paradigm of economic growth.” Growth cannot lead us forward and confront the ecological crisis, if we want to save our biodiversity and our ecosystems; the very systems that enable us to live on Earth.

What about the other projected scenarios? The authors state, “The negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystem functions are projected to continue or worsen in many future scenarios in response to indirect drivers such as rapid human population growth, unsustainable production and consumption and associated technological development.”

One of the major problems of technological development is the enormous amounts of energy and resources it requires to put into place. Even development such as renewable energy like solar and wind power are incredibly resource-hungry, and the only solution to reverse this ecosystem decline is to decrease our energy and resource consumption, not provide more energy in supposedly sustainable ways.

The most effective ways to change

There are many ways in which we can address the ecological crisis. The report states that according to many other studies done internationally, the following are effective ways to create large-scale changes:

- Promoting alternative visions of a good life

- Lowering total consumption and waste

- Unleashing widely-held values of responsibility towards the Earth, to create new norms for sustainability and action

- Addressing inequalities on the social/economic levels