author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 07/12/2023

- No Comments

- Politics

share

The way we feel when we think about climate change and environmental doom is different for each person. Some of us feel hope, others feel powerless and even depressed. What are these eco-emotions, how prevalent are they, and what can we do about them?

In this article...

- Anxiety is an extreme fear of a perceived future threat. Eco-anxiety is the fear that comes from environmental doom and an uncertain future for human societies.

- Around 59% of young people aged 16-25 are very or extremely worried about climate change around the world. This is a widespread phenomenon.

- Eco-anxiety seems to be both an emotional and a behavioural condition. It affects our mood and our ability to function in everyday life.

- Critics of eco-anxiety say that this only occurs when we don’t know the cause of our anxiety and how to act. We know what causes climate change and we know how to reduce our emissions, so we should be furious, not anxious.

- Some of the best ways to cope with eco-anxiety are taking action at a local level, and talking amongst like-minded people about how we feel.

In 2019, the term eco-anxiety became a buzzword in media across the world, with dramatic increases in the use of the term and reporting on the issue. Some years on, the term seems to have dropped from our everyday usage, but the evidence suggests that the phenomena is still widespread, and particularly affects young people.

Eco-emotions refers to the range of emotions that we can feel in response to environmental disasters that occur in our home cities, as well as responses to climate change, the future threat of climate change, and the possible extinction of species or even humanity in the future. Eco-emotions commonly include anxiety, grief, depression, anger, hopelessness, helplessness, powerlessness, sadness, and guilt.

The ecological crisis is a real threat to humanity, and it is one that has been caused by human beings themselves. It is important to state from the beginning that these emotions are normal responses to perceived threats in our everyday life. Real environmental disasters like cyclone Gabrielle in early 2023 are traumatic events for those who are involved, and it is entirely appropriate to feel a range of emotions after these events. Likewise with the threats that climate change pose to our livelihoods: worry and anxiety about the future are quite normal responses to a lack of certainty around how the future will play out.

When looking at ecological emotions, there are a range of commonly used terms which describe particular states related to our responses to climate change. These include, according to Coffey et al.:

- Eco-anxiety: the feeling that arises as a response to worsening environmental conditions, or a chronic fear of environmental collapse.

- Ecological grief: the emotion related to the losses of species and specific environmental or social conditions

- Solastalgia: the distress produced by environmental change within the local or home environment

- Eco-angst: despair at the fragile condition of the planet

- Environmental distress: the lived experience of doom and the desolation of their local or home environment

Eco-anxiety

Solastalgia and eco-anxiety are perhaps two of the most commonly used terms. Eco-anxiety is a form of anxiety, which means that it is an emotion arising out of a fear of something anticipated or something in the future. The American Psychological Association defines it as a chronic fear of environmental doom. Lise van Susteren talks about eco-anxiety as a form of pre-traumatic stress, rather than post-traumatic stress (PTSD). It is a kind of stress that arises now, in the present, but relates to a trauma which is yet to happen, something that exists in the future: climate breakdown, environmental doom, the extinction of species… She says, “We are on the tracks, the train is coming, we can hear it, we can see it, and we’re wondering if we’re going to do what’s necessary to save ourselves in time.” For van Susteren, eco-anxiety is a condition, and not a disorder. The real disorder, for her, is to not have eco-anxiety: this means that someone is not concerned about the future of the planet.

On the other hand, solastalgia is an emotion relating to the present and past environmental disasters that occur close to home. In 2003, the Australian Glenn Albrecht coined the term, and talked about seeing his country disappearing without him actually leaving it. Solastalgia is the suffering that we have in the face of climate destruction: it is watching the rivers dry up, hearing fewer and fewer birds, seeing the trees get diseases… all the small experiences in everyday life that demonstrate a changing climate and environment.

There have been a few articles about eco-anxiety in the New Zealand press, as well as some studies involving eco-emotions amongst university students in Wellington. This Stuff article laments the fact that older generations think that those who experience eco-anxiety are hysterics, and should just calm down. RNZ published a story on eco-anxiety in young people in particular, noting the experiences of some parents regarding their young children, who are experiencing distress because their favourite animals are at risk of extinction. Slightly older children are also distressed because they have realised that their future almost certainly will not be as rosy as it could have been.

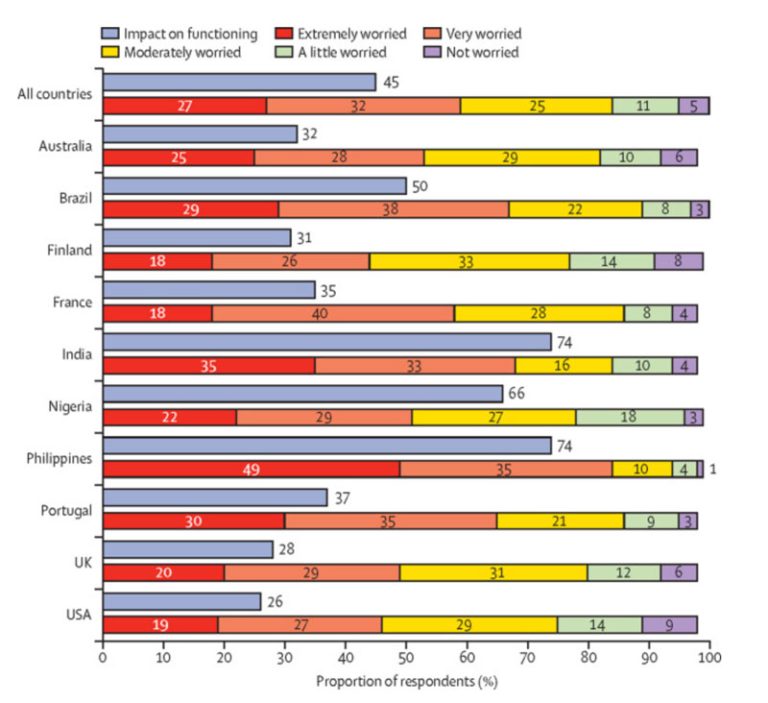

Just how prevalent is eco-anxiety, then? In 2021, a study was published in The Lancet that collated the experiences of 10,000 young people from 10 countries across the globe: “Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey” by Caroline Hickman et al.). Children aged 16-25 were surveyed from Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the UK, and the USA). They found that 59% of respondents were very or extremely worried about the impacts of climate change, and 84% were at least moderately worried. More than 50% reported feeling sad, anxious, powerless, angry, helpless, or guilty.

The researchers wrote: “These factors are likely to increase the risk of developing mental health problems, particularly in more vulnerable individuals such as children and young people, who often face multiple life stressors without having the power to reduce, prevent, or avoid such stressors.” Young people know the risks that are present and they know that their future may not be so bright, but they are quite powerless to do something about it.

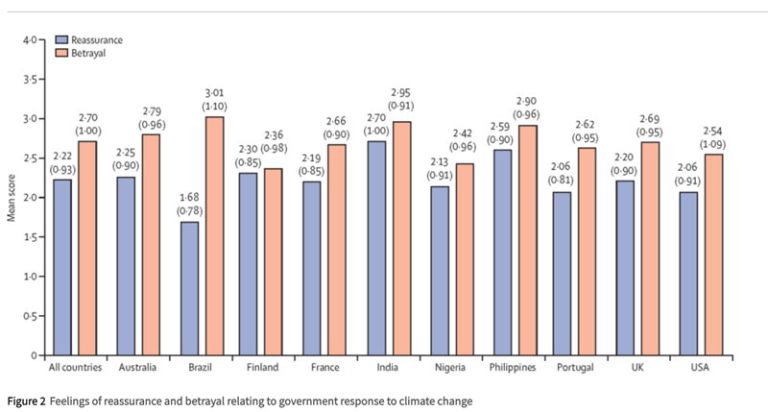

There are many ways that we can respond as a result of experiencing eco-anxiety. The researchers write, “Defence mechanisms against the anxiety provoked by climate change have been well documented, including dismissing, ignoring, disavowing, rationalising, and negating the experiences of others. These behaviours, when exhibited by adults and governments, could be seen as leading to a culture of uncare.” As a result of these adult behaviours, more respondents felt betrayed by their governments than reassured by their actions.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

“The destruction of life forms every day makes me anxious. It’s also the difference between the political announcements and the actions taken to change things. This creates cognitive dissonance and a feeling of a lack of power. I can sometimes let myself be submerged by emotions. When these emotions are really present it’s difficult to have a logical discussion. We end up feeling like we don’t get across the urgency of the problem. I also put a lot of responsibility on myself to act in the right way and make a lot of effort to do certain things which makes life difficult.

I think we must welcome and accept eco-anxiety. It’s a process of mourning for a world and a way of life that is no longer possible, and mourning many, many species that are losing their lives. Action is the best way to leave the state of depression. Taking action, finding friends, and making statements about what you believe in.

I don’t want to cure my eco-anxiety, because I find it healthy.”

Interview with Lucie Lucas, in Vert.eco (translated from the French)

Does eco-anxiety stop people from living normal lives?

For Lucie Lucas, her eco-anxiety was something that motivated her to act. According to much of the research, eco-emotions are often motivating emotions, meaning that they lead to us taking more actions to prevent climate destruction. We can harness these emotions and use them to guide our actions, making positive decisions for our future and the future of our planet.

However, some research suggests that eco-anxiety can also be an emotion that has behavioural consequences: we can no longer function normally in the world as a result. This is one of the reasons why understanding eco-anxiety and its prevalence among young people is particularly important, and could be a potential problem for our societies. Certain studies claim no connection between eco-anxiety and behavioural changes; other studies such as one conducted at Victoria University in Wellington and Canberra University in Australia, claim a clear connection between eco-anxiety and some kind of cognitive impairment.

This study, published in 2021, by Hogg et al., noted that 54% of respondents experience eco-anxiety at least some of the time. Some of the common physical or behavioural responses included changes in mood (20%), unable to sleep or unable to eat (11.38%), trouble concentrating or constant rumination about how one’s actions affect the environment (6%) and an impacted ability to work or study (4.49%).

The aim of the study was to determine a scale or set of behaviours and emotions upon which we could measure eco-anxiety. The Hogg scale, as they called it, measures eco-anxiety with some reliability, and includes both emotional experiences, and behavioural changes, indicating that eco-anxiety is both an emotional and a physical condition.

In 2021, Stanley et. al looked at the impact that eco-emotions might have on our willingness to take action to stop climate change. They looked at three emotions: eco-anxiety, eco-anger, and eco-depression. They found that eco-anger was a good predictor of personal action taken to stop climate change. All three emotions were good predictors of actions taken at a collective level, with eco-depression and eco-anger being most likely to predict collective action. The researchers note that eco-anger might not be the cause of personal action, rather there might just be some relationship between those who experience eco-anger, and those who take personal actions.

Critiques of eco-anxiety

Does eco-anxiety really exist? Is it something we should be talking about, or is it just another way for us to label and categorise an experience, instead of focusing on the actions needed to respond to the ecological crisis?

The German philosopher Gunter Anders said that fear is a necessary stage we must pass through, in order to take meaningful social action. We must feel the fear for a future we do not want, before we are to really commit to living in a different way and fighting for a different future. Anxiety, on the other hand, is a kind of fear when we don’t know what the cause is and we don’t know how to respond to that cause.

This point of view is supported by Frédéric Lordon, a French philosopher and economist. In a contentious and provocative article in Le Monde Diplomatique (in French), he argues that in the large majority of cases, people are not experiencing an anxiety, but a form of fear. Anxiety is a condition which leaves us unable to act, because we are anticipating a problem which has not yet happened. He writes, “Eco-anxiety is to see the climate disaster, but to not have any idea from where this disaster comes or how to address it, to defend oneself.” Climate change, however, is a known problem, and we know what we need to do to respond to this problem: reduce CO2 emissions, reduce our consumption of natural resources, stop industrial farming practices, reduce pollution in waterways, in the ground, and in the air… There are many known actions that need to be taken. It is clear what to do to respond.

The media is presenting eco-anxiety as a new trend, and this, according to Lordon, is a neoliberal tendency to psychologise things – to make normal emotional responses to everyday life into particular psychological conditions that require ‘treatment’. This depoliticises these emotions, meaning that instead of looking at the social and political causes of eco-anxiety, we see that the individual person is at fault for experiencing these emotions and try to ‘cure’ them of their condition or disorder. It becomes ‘your fault’ for worrying about your future, rather than the fault of power imbalances and the actions of a certain few, wealthy and powerful individuals.

This in turn means that we can continue doing very little to confront the ecological crisis, because the media have neutralised the emotions that could lead to positive climate action. Instead of mobilising these emotions, they are referred to as the latest condition to plague young people and make their lives miserable, rendering them incapable of participating normally in society. These particular people need psychological interventions, to help them participate in society – the very society which is causing climate change and ecological disaster. Lordon would say that it is the society that is sick, not the individual.

“The only way to break the deadlock is to repeat the same thing over and over: there is ecocide, it is capitalist, there is no solution capitalist, therefore…

We have to put clear and distinct ideas in the heads of people about what is destroying them. That way, we can’t say we have no idea what to fight against, we can’t say we’re eco-anxious, because we know the cause, and we know what to fight.”

Frédéric Lordon

Lordon prefers to refer to himself and others as eco-furious. He is reacting to the ecological crisis, and also to the fact that very little is being done by governments and those in power to stop this crisis. Instead of being anxious because we don’t know what to do, we should be furious because we know what we need to do, but it is not being done.

A second critique of eco-anxiety asks the question, “who profits from eco-anxiety?” In an article on Vert.eco (in French), Vincent Bresson looks at eco-anxiety as a new way for certain people to make money and capitalise on the emotions of everyday people in a world which works against their interests. He notes that streaming services such as Netflix produce and buy content related to the environmental crisis. They play on the fear of the world disappearing, humans being overtaken by robots, or some calamity wiping out life on earth, to produce content that people pay to watch.

Similarly, there are many conferences and YouTube videos and talks which discuss “transform your climate anxiety into positive action” or “overcoming climate anxiety,” which are sponsored by large groups and corporates. These “gurus”, as Bresson calls them, come onto the stage and talk about how people can turn their climate anxiety into actions such as recycling, living without plastic, driving the car less, giving climate talks in local schools… They do this, instead of drawing attention to the current social and economic systems which lead to climate anxiety, and produce the ecological crisis. Instead of helping people to see that the causes of these problems are also much larger than the individual actions they are responsible for. As a result, many solutions are proposed by budding entrepreneurs looking to turn problems into solutions, such as charging $200 to spend a day in nature hugging trees, visiting a specialist eco-psychologist who will somehow make this uncertain future okay…

These two critiques draw attention to the social and political causes of eco-anxiety, and remind us that an individual is not necessarily responsible for being in a state where they fear their future. However, these critiques miss the mark when it comes to very young people. Children cannot take actions to stop climate change, yet they are coming to understand the implication of the world that they live in. This creates a very real anxiety, which cannot and should not be ignored. The child who is afraid of the elephants becoming extinct probably does not understand enough about why this is the case, and can do almost nothing about this problem. The stress and anxiety this child feels is a condition we should be concerned about, as we introduce more and more climate-related education into our schools.

What to do about eco-anxiety

If you are experiencing eco-anxiety, or any of the other eco-emotions, it can sometimes be difficult to see how to overcome this debilitating worry about the future. This is especially the case when the actions taken by governments and businesses are nowhere near the level necessary to confront the ecological crisis.

There are two things that are particularly effective as strategies to cope with eco-emotions. The first of these is to take action at the local level. This can be in whatever way you like, with whoever you like, and focused on whichever cause you feel most strongly about. For some people, this might be volunteering with a conservation group once a week to plant trees and restore a local habitat. For others it might be joining a climate organisation as the treasurer and helping with their accounting. For others still, it might be starting a climate focus-group in their business or workplace to look at how the business might be rethought, resources might be re-used, and circular principles implemented.

Taking action means that we no longer feel quite so helpless and powerless, and we begin to see that the things we are personally doing can have an impact on the lives of other people and the state of the planet. Every tree we plant, and every discussion we have with colleagues will change the state of the web of connections which forms our cultural fabric. Just as one tree helps an ecosystem to recover, one conversation, one policy adopted in your workplace will help us get closer to the systemic changes which are really needed. By acting, we leave the realm of thoughts and rumination in our heads, and take practical actions to change the world around us. And it feels great!

The second thing we can do is learn to let go of the feeling of personal responsibility for climate change. Yes, some of our actions are responsible global temperatures increasing and biodiversity loss. But unless you are Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos (or a member of this kind of wealthy elite), your real contribution to climate change is infinitesimal. Many of the decisions we make in everyday life are often forced decisions: unless we really go out of our way to live a zero-waste life, the things we buy will be packaged in single-use plastic, and there isn’t much we can do about this, unless a large proportion of consumers take action against the companies that are responsible for these choices. It’s not your fault, and your fault alone, and you cannot bare the burden of the responsibility for climate change. A series of decisions made over centuries of human action have led us to this point – and a large majority of those decisions were made when you were not alive. Climate change isn’t your fault.

Dr. Jackie Feather, a New Zealand psychologist, suggests that opening up and coming back to the present moment are also important strategies to confront eco-anxiety. Instead of imagining a terrible future situation, we can confront the present moment with honesty and look at who we are and what we are doing, and take actions to change the present. The future hasn’t happened yet, and you are not the only person responsible for how this future will play out. But the present moment – that is yours alone to create!

Matthew Adams, a psychology lecturer at the University of Brighton in the UK, emphasises that eco-anxiety cannot be fixed. It is a “normal response to a crisis or threatening situation.” His tips to cope with eco-anxiety include learning to acknowledge and accept difficult emotions, and realising that you are not alone with these emotions. Many young people around the world are feeling similarly powerless and fearful for their future.

Eco-psychologist Mary-Jane Rust talks about the loss of a connection with nature that is prevalent in many Western societies. She says, “There’s a sense of dullness in our comfortable world. We’ve lost a sense of our wild selves. You see many humans go in search of that. We create the adventure that we’ve lost.” By seeking out a connection with the world around us, and creating opportunities for adventure and exploration, we learn to love the wild – the natural environment. This in turn helps us to feel more embodied and to gain wisdom, experiential knowledge, rather than just theoretical knowledge and facts.

The website Carbon Conversations, which has recently become Living with the Climate Crisis, has a set of free resources to help people facilitate sessions where participants explore their eco-emotions and learn strategies to cope with these emotions. This is based on over 15 years of eco-psychology sessions in Oxford, England, started by Rosemary Randall and Andy Brown.

Where to get help

If you are experiencing anxiety or depression that you feel you cannot manage, it’s a good idea to get help from someone who knows and understands these feelings. Contacting a psychologist or psychotherapist near you is a good place to start. It takes courage to recognise that we might not be able to overcome these emotions by ourselves, and it takes time to accept them, but once they become a motivating force, they can lead us towards positive actions, deep friendships, and more meaningful connections with human beings and the natural world.

If you need to talk to someone, there are people ready to help you. In New Zealand, you can call these numbers 24/7:

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP)

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234

Anxiety NZ – 0800 269 4389 (0800 ANXIETY)

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.