author

Jacques Lawinski

post

- 26/10/2023

- No Comments

- Ecology

share

Have we passed the point of no return with the climate and planetary systems? The warning signs are there.

Image: AI-created on perchance.org

Since 2019, a group of scientists have published a “State of the Climate” article which discusses some of the major climate events and climate-related research to date. The 2019 article declared a climate emergency, which has since been signed by 15,000 scientists worldwide. The 2023 article by Ripple et. al has just been published in BioScience here: The 2023 state of the climate report: Entering uncharted territory.

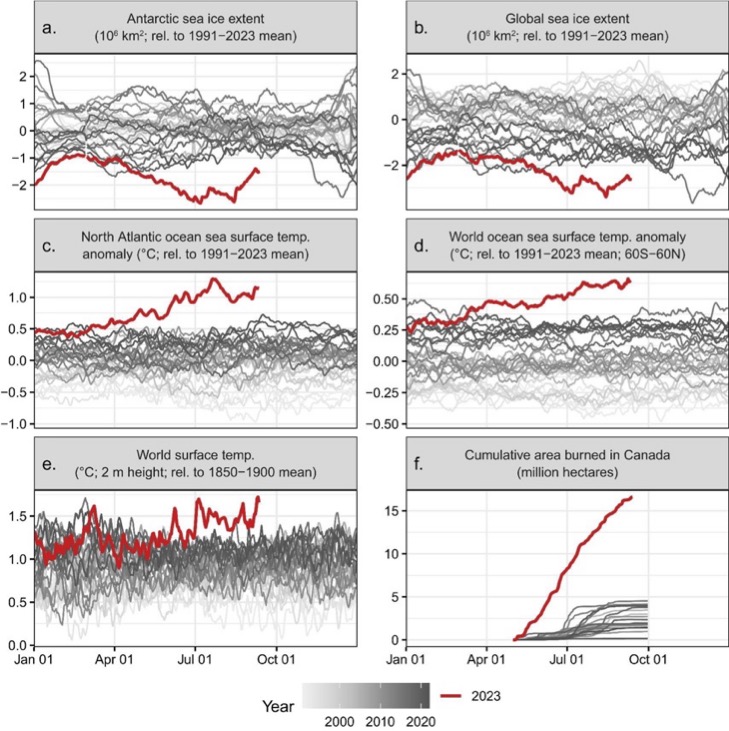

2023 has been particularly notable as a year of climate instability, major climate disasters, and records being broken by huge margins. Scientists are concerned because 20 of the 35 different “vital signs” for the health of the planetary system are now at record extreme levels.

The authors write, “The rapid pace of change has surprised scientists and caused concern about the dangers of extreme weather, risky climate feedback loops, and the approach of damaging tipping points sooner than expected.”

The authors, climate scientists, are surprised by the magnitude of the changes we are seeing: “Even more striking are the enormous margins by which 2023 conditions are exceeding past extremes.” As we see in the image, following the red line for 2023 shows huge differences compared to past norms on these six different metrics for climate change.

Why are scientists surprised?

Climate science has always been approximative – we make the best guesses we can about the possibility of extreme weather events in the years to come, but this is only based on the information we know about the climate. The existence of so-called ‘tipping points’ is not necessarily something that exists in nature, but rather a way for human beings to mark out the point at which a system which was previously quite stable, becomes very unstable. Just when and where these tipping points are, and what causes them to be reached, is still the topic of much scientific research.

Because we still know so little about the climate system, and the Earth’s other regulating systems, it’s difficult to know whether the predictions that have been made will be accurate in the future. It would seem that the rise in unpredictable climate events has occurred sooner than we thought – many climate scientists have predicted reaching or passing tipping points around 2030. However, we may have already gone too far, and already passed the point at which the planet can cope with our activities.

350 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is the goal we have for a safe and stable climate system. In 2023, we reached 420 parts per million, and this number is increasing year-on-year. Global emissions are not decreasing, which they must do in order for humanity to confront the climate crisis.

You're reading an article on Plurality.eco, a site dedicated to understanding the ecological crisis. All our articles are free, without advertising. To stay up to date with what we publish, enter your email address below.

The challenge for scientists

The article reads a little bit like something from the film Don’t Look Up, which explored the emotions scientists feel towards societies which don’t act in the face of a disaster. In the film, the group of scientists who discovered that a meteorite was going to destroy life on Earth attempted to warn people, but in the end, those in charge and some parts of the population chose not to listen to these warnings – and not to act in the face of them. In the face of this, the scientists became emotional – angry, sad – and therefore lost the objectivity that we like to think science has.

The series of State of the Climate articles are hotly debated amongst scientists for their lack of real rigour, and the inclusion of moral sentiments and the promotion of certain solutions. The group of scientists responsible for these articles have started talking about what we should and should not do, rather than just presenting what we know about the situation. Is this the role of the scientist?

For example, the report states “We also call to stabilize and gradually decrease the human population with gender justice through voluntary family planning and by supporting women’s and girls’ education and rights, which reduces fertility rates and raises the standard of living (Bongaarts and O’Neill 2018).”

Is the reduction of the human population through fertility control an acceptable conclusion for a scientist to make about climate change? And is an article on the state of the climate the right place for this kind of opinion?

It is difficult for scientists to balance the care they feel towards their lives, their loved ones, their countries, and planet Earth, with the requirement that we place on them to be objective and only present what we know as fact.

The report also relies a lot on media reports, and includes photographs of climate-related damage. We could also ask, is this kind of strategy, to elicit an emotional response in a scientific article, the right way to present information to other scientists and the public? Or does it, once again, cost us the objectivity that we require of the sciences?

Being a climate scientist and reporting on the state of the climate is tough. Especially when the facts paint a very distressing picture of the future of life on planet Earth. That is why it’s particularly important to act now. Every tenth of a degree of warming sets up a more hospitable future. You can act to reduce your emissions, talk to your local council or Member of Parliament about their plans to respond to climate change, and try to discuss climate change with your friends and family.

More on climate science...

To understand more about the climate crisis, and the larger ecological crisis, read our article What is the Ecological Crisis here.

To read about the climate science that we currently have, from the IPCC report earlier this year, read our summary article here.

To read about what we know about biodiversity and ecosystem services, check out our article on the IPBES report here.

You can also donate to Plurality.eco, to support articles like this breaking down climate science and bringing a balanced perspective to the climate debate.

It took more than 30 hours of research and writing to produce this article, which will always be open and free for everyone to read, without any advertising.

All our articles are freely accessible because we believe that everyone needs to be able to access to a source of coherent and easy to understand information on the ecological crisis. This challenge that confronts us all will only be properly addressed when we understand what the problems are and where they come from.

If you've learned something today, please consider donating, to help us produce more great articles and share this knowledge with a wider audience.

Why plurality.eco?

Our environment is more than a resource to be exploited. Human beings are not the ‘masters of nature,’ and cannot think they are managers of everything around them. Plurality is about finding a wealth of ideas to help us cope with the ecological crisis which we have to confront now, and in the coming decades. We all need to understand what is at stake, and create new ways of being in the world, new dreams for ourselves, that recognise this uncertain future.